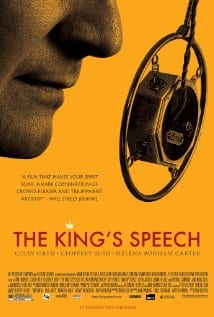

Many films have portrayed characters who stutter, but stuttering itself has rarely been the subject of a popular movie. That all changed with The King’s Speech, which made headlines last weekend at the 83rd annual Academy Awards and swept four of the most coveted award categories (Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay, and Best Actor). This film tells the true story of King George VI, a man struggling with a stutter who suddenly finds himself thrust onto the global stage when his father dies and his brother abdicates the throne. With the help of an unconventional speech therapist, George VI gains the confidence and vocal control needed to inspire an entire empire about to enter the second World War.

The King’s Speech brings attention to one of the most common speech disorders. Stuttering — repetition of or difficulty starting words, syllables, or phrases — affects up to 5% of children, and although most cases resolve within a few years, it continues to affect about 1% of adults. If you stutter, you’re in good company: in addition to King George VI, famous and accomplished stutterers include Winston Churchill, business executive Jack Welch, Vice President Joe Biden, composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, Marilyn Monroe, James Earl Jones, Nicole Kidman, NFL runningback Adrian Peterson, author Lewis Carroll, and Charles Darwin, to name only a few.

Although researchers don’t always know the exact causes of stuttering, there are a number of factors known to be involved. Some cases of stuttering can be attributed to language development — when a child’s vocal abilities can’t keep up with what they want to say — or disruptions in signaling between the brain and speaking organs, as might be caused by a brain injury. But stuttering is also much more common in boys, and tends to run in families, suggesting genetics plays an important role.

Last year, a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine identified for the first time specific genetic variants associated with stuttering. By analyzing DNA from a large Pakistani family, the researchers found a variant in the gene GNPTAB that was present in 25 out of 28 stutterers in that family. When they looked at this variant in other unrelated Pakistani stutterers and non-stutterers, they found it was present in about 10% of the stutterers but only about 1% of the non-stutterers. A follow-up study of this variant revealed that it likely arose from a single mutation event in an individual who lived about 570 generations ago.

Additional analysis in a larger sample of individuals of mainly European ancestry identified other, rarer mutations that may be associated with stuttering in GNPTAB as well as the GNPTG and NAGPA genes, which are closely related to GNPTAB in function. Certain mutations in the GNPTAB and GNPTG genes cause mucolipidosis, a rare, recessively-inherited disorder that affects many major organs and the motor and skeletal systems. Mucolipidosis is also often characterized by developmental problems and speech deficits, providing a link as to why other variants in these genes may predispose to stuttering and pointing to specific biological pathways that may be involved in common speech disorders.

“The King’s Speech has truly given a voice to the voiceless, hope to those who had none, and courage to those who struggle daily to be heard,” said Stuttering Foundation President Jane Fraser in a press release. With the latest spotlight from the success of The King’s Speech, many hope that even more progress will be made towards awareness of stuttering and research into understanding its causes, both genetic and non-genetic.