As we have shown time and again here at the Blog, our DNA can greatly illuminate the lives of our most ancient ancestors. We’ve learned how the ancient Phoenicians left their genetic footprints scattered across the Mediterranean Sea, and seen the DNA signatures of the first farmers sprinkled everywhere from Iraq to Germany to England. But DNA can also tell us many things about our species’ more recent history as well. Just yesterday we discussed the most recent discoveries regarding the fate of Russia’s last royal family, the Romanovs. Below we delve deeper into that mystery, as well as two others that reveal how scientists have harnessed the power of DNA to solve some of history’s seemingly unsolvable mysteries.

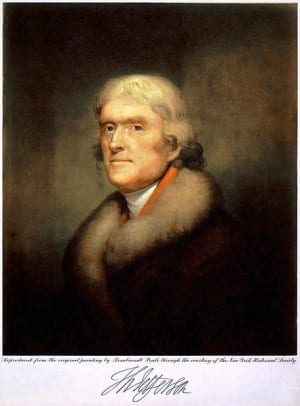

Which was Jefferson’s Son?

Tales of an affair between our third president, Thomas Jefferson, and his household slave, Sally Hemings, began circulating as soon as the two returned from Paris in 1790. For her entire life, Hemings served Jefferson and his family at his residence in Virginia. She bore at least four children throughout her life. And though the father of Sally’s children was never divulged, anecdotal evidence, combined with the efforts of a persistent political reporter named James T. Callender, helped spread rumors that the third President of the United States fathered at least one of Hemings’ children.

Two of Hemings’ sons were of particular interest. The first, Thomas Woodson, was believed to have been conceived while Hemings and Jefferson were living in Paris. Convincing the public that Woodson was indeed the illegitimate son of Hemings and Jefferson was one of Callender’s primary goals.

The other child of interest, Eston Hemings, was Sally’s youngest. He was born in 1808 and was said to have resembled Thomas Jefferson, and clearly the potential connection was not lost on him: later in his life Eston Hemings moved to Madison, Wisc., and changed his name to Eston Hemings Jefferson.

Yet even with this name change, many of Eston’s descendants seemed to have no knowledge of their potential ancestry. And most historians placed more credence on the idea that Woodson was Jefferson’s son. In order to discover the true ancestry of both Thomas Woodson and Eston Hemings, researchers turned to DNA.

Geneticists found living males who could document their descent from either Thomas Woodson, Eston Hemings, or Thomas Jefferson along a purely male line. Because the Y chromosome is passed down directly from father to son, the paternal descendant of any of Thomas Jefferson’s sons would have the same Y chromosome as a descendant of Jefferson himself.

The first thing the geneticists found when they examined the Y chromosomes of all these descendants was that Jefferson himself had a very rare Y chromosome type hardly ever found among people of western European ancestry. Then, when they examined the DNA of Woodson’s and Hemings’ descendants, they found a perfect match: but only with Eston Hemings’ descendants. Woodson’s descendants all had a Y chromosome that is common among West Africans.

So even though DNA evidence disproved historians’ suspicion that Sally Hemings’ first son, Thomas Woodson, was fathered by our nation’s third president, it strongly suggested that her youngest, Eston Hemings, was indeed Jefferson’s offspring.

The Case of the Missing Mozart

On December 6, 1791, famed composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was laid to rest at St. Mark’s Cemetery in Vienna. Despite his fame, he was buried in a pauper’s grave, along with several dozen others. But 10 years later, gravedigger Joseph Rothmayer unearthed Mozart and removed his skull, speculating that there was money to be made from selling the relic. For the next 200 years, the skull would disappear and and then reappear into the hands of various collectors and Mozart enthusiasts. Its authenticity could never be verified, so scientists finally turned to DNA to fill in the gaps that other research could not.

In 2005, two independent teams of geneticists analyzed DNA extracted from a tooth in the skull. They compared this DNA to various members of Mozart’s family, including his father, grandmother, and niece, who were all buried in the Mozart family tomb.

Both teams arrived at the exact same conclusion: the skull could not have been Mozart’s. The DNA extracted from the skull differed too much from that of every family member buried in the Mozart tomb.

Lost and Found: The Grand Duchess Anastasia

On July 16th, 1918, a family of seven, along with their three servants and physician, were murdered outside the small town of Ekaterinburg, Russia. But this was no ordinary family. This father was Tsar Nicolas – the last Romanov Emperor of Russia. As the Russian Revolution was coming to a head, the imperial family was arrested and held by the Bolshevik rebels. Then, over a year later, they were held at gunpoint and shot execution style; their bodies were hastily burned and thrown in a shallow grave in the woods outside the town.

Just a few short years after their murder, rumors began circulating that at least one member of the Romanov family had escaped execution. At exactly the right moment, a young woman emerged in Germany and claimed to be Grand Duchess Anastasia, one of the Tsar’s daughters. For the next 60 years, this woman, known as Anna Anderson, stood by her claim that she was Anastasia, and that she had managed to escape the execution in Ekaterinburg. Her assertions were given extra credence when two amateur historians unearthed a grave site that they claimed contained the remains of the Romanov family, minus the body of Anastasia. The rumors grew. Yet the royal houses of Europe, to whom the Romanovs were related, never believed Anderson’s story. The two sides were in a constant struggle for the truth up to Anderson’s death in 1984.

More on the Tsarina

As with Jefferson and Mozart, researchers finally turned to DNA evidence to test Anderson’s claim. Scientists retrieved DNA from a tissue sample that had been stored in a hospital after Anderson had a biopsy, and extracted her mitochondrial DNA. Because mitochondrial DNA is passed down from mother to children, scientists could compare Anderson’s mtDNA to a living maternal relative of Anastasia. The relative they chose happened to be Prince Phillip of Great Britain: husband to Queen Elizabeth II and grand-nephew of Nicolas’ wife, Tsarina Alexandra.

Anderson’s mtDNA did not match that of Prince Phillip, however. And when new techniques allowed for the extraction of DNA from the burial site in Ekaterinburg, scientists found that Anderson’s DNA did not match that of the Tsarina or the other children. To finally close this case, in 2007 archaeologists discovered another grave in Ekaterinburg, near the original, that held more bodies. Forensic analysis strongly suggested that one of these bodies was the missing Anastasia.

Even though some die-hard fans of Anderson maintain she was always telling the truth, the vast majority of scientists and historians consider her simply a master of deception. Once again, DNA analysis has been able to prove – or in this case, disprove – a seemingly unsolvable mystery.