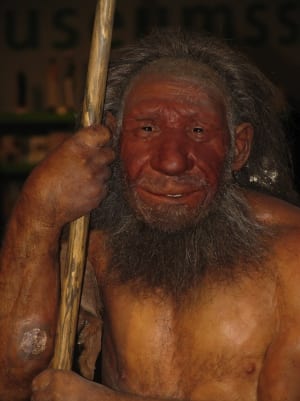

The Neanderthals have always held a special place in the field of anthropology. The skeletal remains of our short, stocky evolutionary relatives have been found everywhere from Spain to Iraq.

Their physical likeness to our own species, and the possibility that humans and Neanderthals may have interacted, has long fascinated experts and enthusiastic novices alike. But simply studying their skeletal remains and artifacts seemed to leave more questions than answers.

More than 10 years ago an international team of scientists became the first to extract and analyze ancient DNA (aDNA) from a Neanderthal skeleton. By examining the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) – which is more abundant in our cells than our nuclear DNA and therefore more likely to preserve – they found that there were enough genetic differences between this Neanderthal and modern humans to classify the two as separate species.

Since this initial foray into Neanderthal genetics there have been attempts to improve aDNA analysis, with the goal of filling in the gaps that traditional anthropological techniques had been unable to. Earlier this year, scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology became the first to sequence the entire Neanderthal mitochondrial genome – no easy feat. Now scientists have taken aDNA analysis to the next level by developing a novel technique to extract it more easily, yielding the most comprehensive and accurate results to date. Along the way, they have uncovered some intriguing clues to the possible fate of the Neanderthals. Their results are reported in the July 17 issue of Science.

This new study, also led by Max Planck Institute scientists, centers around a novel method for finding and extracting that elusive aDNA from Neanderthal remains. The study took advantage of a new kind of aDNA extraction process, called Primer Extension Capture (PEC). This technique has many advantages over the others, primarily because it allows the aDNA to be completely isolated from all the other molecular junk that can accumulate over time. This yields highly accurate results with much less effort. So instead of simply using this technique on one Neanderthal individual, they analyzed five.

The remains they chose had been excavated from a variety of locations, from Croatia to Germany to Spain and Russia. Most of the remains were between 35,000 and 40,000 years old, which is very close to when Neanderthals were believed to have disappeared from most of their range. They also examined Neanderthal remains from Russia that dated to between 60,000 and 70,000 years old.

After successfully extracting and analyzing the DNA of these remains, the researchers came to a few startling conclusions. First, the level of genetic diversity among the samples was exceedingly low. In fact, the amount of genetic diversity of the Neanderthal samples was less than one-third the diversity we see in modern humans today. For example, two of the samples — one from Croatia and the other from Germany — had identical mtDNA genomes. For two individuals living nearly 1,000 miles apart, this is quite unusual; unless there wasn’t much variation in mtDNA in the first place.

The authors of this report think this genetic homogeneity means that there were far fewer Neanderthals living in Europe and western Asia than they’d previously thought. Based on their analysis of the five individuals, the they estimated that the total population size of Neanderthals in Europe 35,000 years ago may have had as few as 3,500 females (because mtDNA is passed down maternally, it cannot be used to estimate male population size).

The authors believe there are two possible explanations for this small population size. The first is that, over the 400,000 year history of Neanderthals, their population may have always been small. After all, for much of their existence they survived harsh ice age conditions, so low population size may have been necessary for survival.

But the authors offer an alternate explanation as well. They think this small population size is the result of long-term population decline, perhaps beginning about 40,000 years ago and continuing until Neanderthals were wiped out. To test their hypothesis, the researchers re-analyzed the Neanderthal mtDNA genomes and found that their protein-encoding genes had evolved much more quickly than those of humans or chimpanzees since the three species split, millions of years ago.

This high rate of evolution, the authors argue, was not present in the older Russian Neanderthal sample. This fact implies a pattern of decline in population size, not a population that had been small from the start. These results support their idea that the Neanderthal numbers were on the decline. Without direct evidence, they can only speculate as to the cause of of their decline, but the scientists believe it may be tied to the arrival of humans in Europe and western Asia about 40,000 years ago.

Today most experts believe the Neanderthals were being out-competed by the incoming humans, who had superior technology and language skills. Over time, the Neanderthals were forced to move to more isolated regions in the mountains of France and Spain. By 30,000 years ago, only a few traces remained. Soon after, they were gone. This study reveals some compelling evidence that humans were in fact responsible – whether directly or indirectly – for the demise of the Neanderthals.