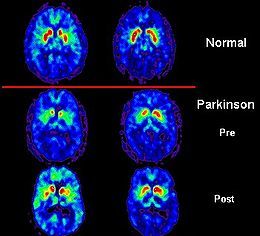

PET scans showing dopamine activity in a normal brain and a Parkinson’s patient’s before and after treatment with a therapeutic implant.

PET scans showing dopamine activity in a normal brain and a Parkinson’s patient’s before and after treatment with a therapeutic implant.

More than a million Americans have Parkinson’s disease, and another 50,000 are diagnosed each year.

Scientists know that many of Parkinson’s’s characteristic symptoms—tremors, rigid muscles, and movement problems—can be traced back to the loss of dopamine-producing brain cells. But what researchers don’t fully understand is why these cells are damaged in the first place.

Genetics and Other Factors

For most cases of Parkinson’s, the brain cell damage is probably the result of complex interactions between multiple genetic and environmental factors. Despite years of work, however, hardly any of these factors are known. But now two research groups have identified several genetic variants associated with the risk of Parkinson’s in Asian and Caucasian populations. Their results were published online this week in the journal Nature Genetics.

One group, led by Wataru Satake, analyzed the DNA of 2,011 Japanese people with Parkinson’s disease and 18,381 controls. The other group, composed of U.S. and German researchers (Simón-Sánchez et al.), looked at the genetics of 5,074 Caucasians with Parkinson’s and 8,551 without the disease.

Common Genetic Variants

Common variations in and around two genes previously associated with rare familial forms of Parkinson’s disease, SNCA, and LRRK2, were associated with the risk for Parkinson’s in the Japanese study. In the Caucasian study, the association with SNCA was strong, but the evidence for an association between Parkinson’s and common variation near LRRK2 was only suggestive. Given that the association of mutations in this gene with familial forms of Parkinson’s is so strong, Simón-Sánchez et al. nevertheless think there truly is a role for SNPs near this gene in non-familial forms of the disease.

Satake et al. also found that variations in a region of the genome not previously linked to Parkinson’s disease could affect the risk for the disease. This region of chromosome 1 contains several genes, and it is unclear which one might be involved in Parkinson’s. Satake et al. named the region PARK16. After comparing their data, the U.S./German group also found a link between Parkinson’s disease and the PARK16 region.

A SNP in the BST1 gene was associated with increased risk for Parkinson’s in the Japanese sample, but did not show any link to the disease in the Caucasian sample. The risk version of this SNP, however, is found at very low levels in Caucasians. This may have been why Simón-Sánchez et al. were unable to pick it up in their analysis.

The MAPT Gene

Finally, a SNP in the MAPT gene, which has also been associated with familial forms of Parkinson’s, was associated with disease risk in the Caucasian sample but not in the Japanese.

Work to find common genetic variations affecting the risk for Parkinson’s will no doubt continue as researchers try to identify all of the puzzle pieces relevant to this devastating disease and how they fit together.

“A further increase in the number and size of cohorts for [genomewide association studies] in [Parkinson’s disease] will likely reveal additional common genetic risk loci, and these, in turn, will improve understanding and, ultimately, treatment of this devastating disorder,” concludes Simón-Sánchez et al.

Although variations in some of the same genes were found in both the Caucasian and Japanese samples, the same SNPs often do not apply to the different populations. People looking up their own data should use the SNPs listed for the ethnicity they identify most closely with.

*Risk version is more standard version of SNP.

**Results did not meet strict cut offs for statistical significance, but researchers suggest the associations are nonetheless real.