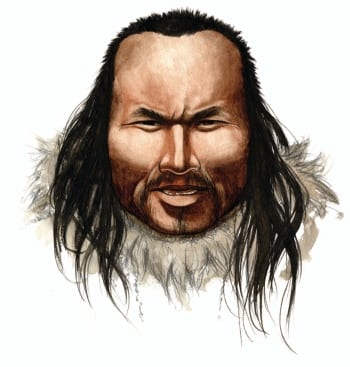

Artist’s impression of Inuk based on genetic analysis

Artist’s impression of Inuk based on genetic analysis

Nuka Godfredsen/Nature

Editor’s note: This post has been edited from the original to reflect changes in 23andMe’s product.

Tufts of hair rescued from the permafrost in Greenland and then tucked away in a basement in Denmark for more than 20 years have given scientists their first glimpse into the genetics of an ancient human.

Eske Willerslev and Morten Rasmussen of the Centre for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen, along with an international team of collaborators, have sequenced 80% of the genome of a man from the Saqqaq Culture who walked the earth about 4,000 years ago. By comparing this ancient DNA sequence to what is known about the genetics of modern humans, the researchers were able to piece together a picture of what the man they call Inuk (“human” or “man” in Greenlandic) likely looked like, where his people came from, and how he’s related to modern populations. The results were published online today in the journal Nature.

Inuk’s DNA revealed that he had type A+ blood. He likely had brown eyes and thick, dark hair. His skin was probably not the light color found in modern day Europeans. Inuk’s earwax was dry and he had shovel-graded front teeth, both characteristics common in Asian and Native American populations. Several of the genetic variants he carried suggest that he had a metabolism and body mass well-suited to cold climates. The researchers even found that Inuk’s genetics are indicative of an increased risk of baldness.

“Because we found quite a lot of hair from this guy, we presume he died quite young,” Willerslev said in a press briefing.

(Although as Harvard professor and Luxuriant Flowing Hair Club for Scientists member Steven Pinker found when analysis of his DNA also suggested a propensity for baldness, DNA is not always destiny.)

Analysis of Inuk’s Y chromosome revealed that his paternal haplogroup is Q1a, which is commonly found among Siberian and Native American populations. Previous analysis by the same research group had revealed that Inuk’s maternal haplogroup, determined by his mitochondrial DNA, is D2a1. This same lineage is commonly found in modern-day Aleuts of the Commander Islands in the Bering Sea and the Siberian Sireniki Yuits (Asian Eskimos).

Since discovery of the remains of the Saqqaq Culture in the 1950s, there has been disagreement over how these people were related to others that crossed the Bering Strait into the New World. By analyzing Inuk’s DNA and comparing it to modern populations, the researchers determined that the Saqqaq are most closely related to the Nganasans, Koryaks and Chukchis of Siberia. The long-gone Saqqaqs most likely left Siberia for the New World about 5,500 years ago, independently from the ancestors of present-day Native Americans and Inuit.

Now that his team has shown that full genome sequence analysis of ancient samples is feasible, Willerslev expects that there will be an explosion of work in the field. He says that sequencing of DNA from South American mummies could help illuminate the population history and genetic diversity of Native Americans from before the arrival of Europeans. Willerslev also suggests that sequencing ancient human DNA could reveal when certain genetic diseases become prevalent in different populations.