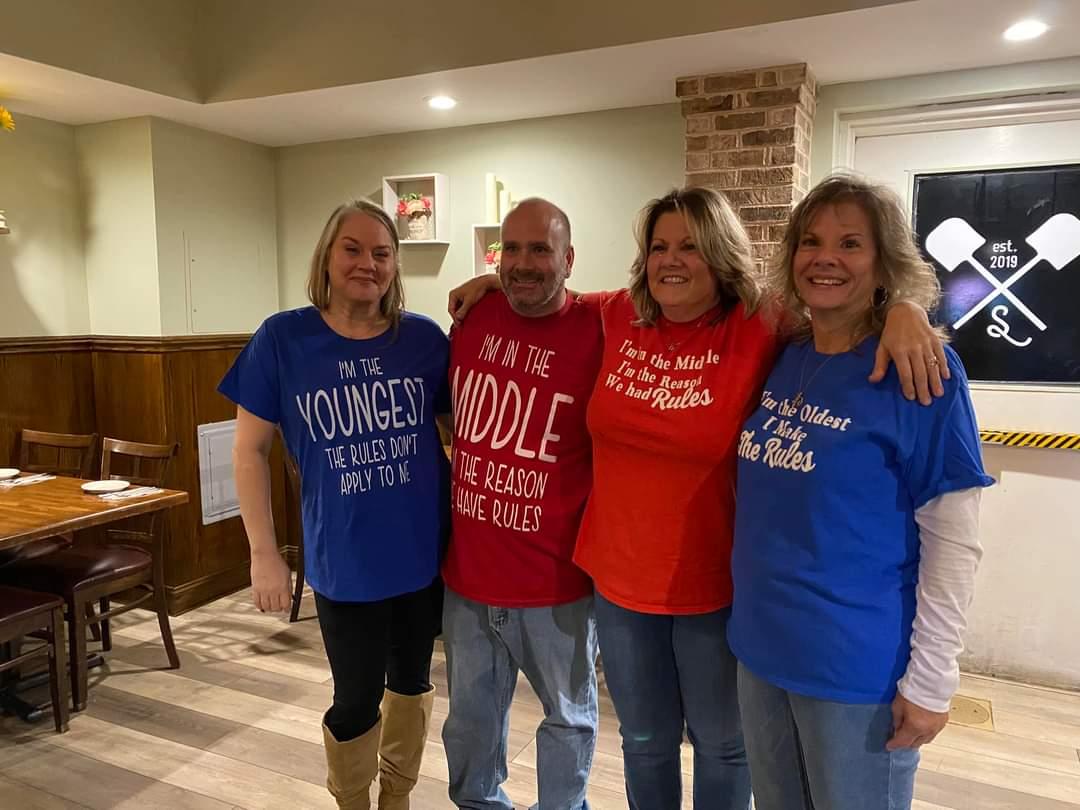

Editor’s Note 5/11/23: Since first sharing her story in 2021, Jenn has gone through treatment. She was kind enough to share that with us which was put together in a video by Freethink.

When she began exploring her 23andMe results, Jenn Ford knew she’d learn something interesting about herself — her traits or her ancestry.

But she hadn’t expected to find out something so profoundly important for both her and her family’s health.

“I believe that knowledge is power, and the more I know, the more I can do about it,” she said recently.

Something Unexpected

A long-time customer, Jenn first began using 23andMe in 2016 when she learned that her family’s ancestry was primarily Italian, French, German, and Lithuanian. However, she was surprised to see that it also included a tiny amount of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, about .2 percent, according to her 23andMe Ancestry Composition report.

It was all fascinating and fun, but nothing unexpected. That changed in 2018 when 23andMe released its BRCA1/BRCA2 (Selected Variants) Genetic Health Risk Report.*

When it became available, Jenn wanted to take a look at her report. So, she opened it up after opting in to receive the information and going through an educational module about the report.

“Oh, that’s strange,” she said to herself after scanning the report while at a family cookout.

The report indicated she had one of the three variants for which 23andMe tests. She quickly closed her report thinking she’d spend a little more time looking at it later. But, having spent almost ten years as an Oncology Technician at Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Jenn knew this was something she couldn’t ignore.

“I have a medical brain, and I can understand what something like this could mean,” she said.

Turning to a Genetic Counselor

When she got home, she opened up her report again, and this time carefully read through it all, even rereading portions of it to her husband, Andrew.

23andMe’s report looks at three selected variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that are most common in people of Ashkenazi ancestry. Females with one of these variants — no matter their ancestry — have a 45-85 percent risk of developing breast cancer by age 70, compared to about 13 percent in the general population. In addition, having one of these variants increases the risk of developing ovarian and pancreatic cancer in females. It can also increase the risk of developing male breast cancer, pancreatic and prostate cancer in men.

At first, she wondered if there could have been a mistake. Then she thought a bit about her family’s health history. On her mother’s side, her relatives were all reasonably healthy. On her dad’s side, however, cancer has stalked generations. So even though her Ashkenazi ancestry was very, very small, she wondered if this variant that is more common in people of Ashkenazi ancestry may have been passed to her from her father’s side of the family. Jenn then called a friend who works in oncology. She ran through her report and got an almost immediate reaction.

‘”Oh my God, you need to see a genetic counselor,”‘ Jenn recalls her saying.

Waiting

Living not far from one of the world’s premier cancer centers, Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, she reached out to make an appointment to see a doctor and a genetic counselor.

“It was the longest five weeks, ever,” Jenn said.

At her appointment, the first reaction from her doctors at Dana Farber was surprised that 23andMe tested for these three selected variants. Next, after confirming her result, the doctors told Jenn that having one of these variants significantly elevated her risk for breast and ovarian cancer. They then started helping her to better understand what that risk meant, and what options she might consider. Finally, they sent her to see the gynecological oncologist, who estimated her risk of developing cancer was likely more than 75 percent, she said.

The next question was what to do about it. One approach would be to wait, have regular and more frequent medical screening for breast cancer, and to consider ovarian cancer screening. She was also told that every six months she would need to undergo testing in order to make sure that her scans were clean and she was cancer-free. That was something Jenn and her husband did not want to go through as a family, testing and waiting every six months. Another approach was prophylactic surgery to remove her breasts, ovaries, and fallopian tubes, significantly reducing the risk.

“I was 35, we had our two girls, and I knew I was done having children,’ she said. “I didn’t want to deal with living with this risk and just waiting.”

Taking Action

She decided on preventative surgery and wanted to move quickly.

“I just knew I was going to have to get surgery,” she said.

It wasn’t easy. It required several different surgeries for removal and reconstruction and all the time for recovery. And just as Jenn had very quickly understood how important this information was to her, she also understood that it was also crucial for her family. Her result didn’t just trigger a conversation with her doctor. It also started discussions with her adult family members. Jenn knew that the same genetic variant that put her at a higher risk of developing cancer might impact them. She thought of her two young daughters and that they had a 50 percent chance of inheriting the risk variant. It would be something they would need to know about when they were adults, Jenn said. She also thought about her other relatives and how this genetic risk might explain cancer and the deaths of many women in her family, she thought.

The Cascade Effect

There’s something called the cascade effect. It refers to a chain of events that unfold from one initial action, something that’s often unforeseen. So often, people think of this negatively, as in the collapse of a building or a stock market crash. But there are also positive cascades, a chain of events that trigger positive outcomes from one person to the next.

Several years ago, 23andMe researchers did a small study about how people responded to learning of an unexpected genetic health risk for cancer via their 23andMe report. That study found that those who learned they carried a BRCA risk variant generally took appropriate actions. For example, they talked to their doctors and shared their results with family members. The study showed that the result created a “cascade effect” that benefited relatives who might not know of the family risk for these hereditary cancers.

Jenn’s 23andMe story is a little like that.

“I have always known that certain cancers were prevalent in my dad’s family, but no one had received any genetic testing until this point. Which now, in retrospect, blows me away,” she said.

After she talked to her parents about her results, her dad got a genetic test ordered by his doctor. He, too, had the risk variant, confirming that it came from his side of the family. Last year, a little more than two years later, he learned through screening that he had prostate cancer. He had surgery and, to date, remains cancer-free.

“If I had not used 23andMe, I would not have taken the steps that I have taken to ensure that I live a long and healthy life,” Jenn said. “My Dad would likely not have found his prostate cancer until it was too late. Thank you, 23andMe.”

Learn more about the BRCA gene and its role in some cancers here.

Note:

*23andMe health predisposition reports include both reports that meet FDA requirements for genetic health risks and reports which are based on 23andMe research and have not been reviewed by the FDA. The test uses qualitative genotyping to detect select clinically relevant variants in the genomic DNA of adults from saliva for the purpose of reporting and interpreting genetic health risks. It is not intended to diagnose any disease. Your ethnicity may affect the relevance of each report and how your genetic health risk results are interpreted. Each genetic health risk report describes if a person has variants associated with a higher risk of developing a disease, but does not describe a person’s overall risk of developing the disease. The test is not intended to tell you anything about your current state of health, or to be used to make medical decisions, including whether or not you should take a medication, how much of a medication you should take, or determine any treatment. For certain conditions, we provide a single report that includes information on both carrier status and genetic health risk.

Warnings & Limitations:

The 23andMe PGS Genetic Health Risk Report for BRCA1/BRCA2 (Selected Variants) is indicated for reporting of the 185delAG and 5382insC variants in the BRCA1 gene and the 6174delT variant in the BRCA2 gene. The report describes if a woman is at increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, and if a man is at increased risk of developing breast cancer or may be at increased risk of developing prostate cancer. The three variants included in this report are most common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and do not represent the majority of BRCA1/BRCA2 variants in the general population. This report does not include variants in other genes linked to hereditary cancers and the absence of variants included in this report does not rule out the presence of other genetic variants that may impact cancer risk. The PGS test is not a substitute for visits to a healthcare professional for recommended screenings or appropriate follow-up. Results should be confirmed in a clinical setting before taking any medical action. For important information and limitations regarding each genetic health risk report, visit 23andme.com/test-info/.