Thomas Park Clement helped hundreds of Korean adoptees like him use DNA testing to connect for the first time with biological relatives. Strangely, up until a few years ago, he’d never thought about tracking down his birth parents.

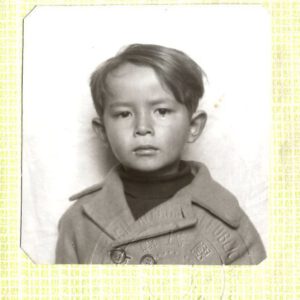

A passport photo of Thomas was taken before his adoption.

“I don’t know why,” Thomas said in a podcast last year.

He never had the urge, he said. Maybe he was too busy.

A prolific inventor, entrepreneur, and now philanthropist, Thomas was a long way from the biracial boy abandoned in Seoul, South Korea in the 1950s. He never forgot where he came from, but he also didn’t feel the need to go back and find his biological relatives.

Sharing his Gifts

Thomas was born during the Korean War to a Korean mother and an American soldier. By the time he was four, his father had left. The last time he saw his mother, Thomas was on a corner near a crowded market in Seoul. She told him to walk down the street and not look back. He never did.

Thomas lived on the streets and then in a rough-and-tumble orphanage. After a few harrowing years, an American family adopted him and brought him to the United States.

It took some time for Thomas to shake the years of deprivation from his psyche. During his first birthday celebration in the U.S., he gathered all the gifts he received and put them in a corner where he guarded them. At the same time, the rest of the children played and enjoyed the party. It was only later that he realized he’d missed out.

“I decided I didn’t want to miss one more party so (in the future) I would share my ‘presents’ with everybody,” he said.

He never forgot the lesson, so he’s made a point of giving back.

Giving Back

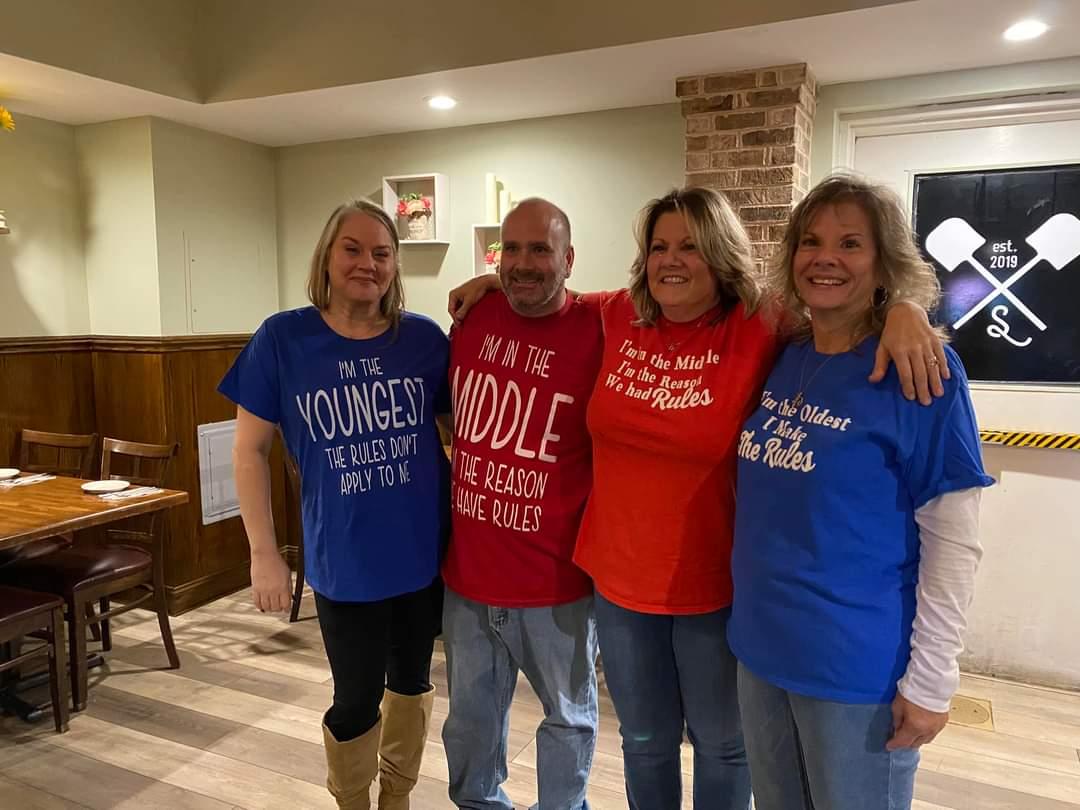

Among his philanthropic gifts was a donation of $1 million to cover the costs for DNA testing for hundreds of Korean adoptees. Many have shared their stories with him: sons and daughters finding their mothers or fathers, brothers and sisters finding each other, and even identical twins finding one another.

“You have to remember these are people who up until then had never even met a biological relative,” Thomas said.

And many had tried without success to find anything about their families. Some just wanted to connect with their Korean roots. International Adoptions in the United States didn’t begin in earnest until 1955 and the passage of the Bill for Relief of Certain War Orphans. At first, the large-scale international adoptions were from Korea coming just after the Korean War. For at least 40 years, most international adoptions originated in Korea, with at least 200,000 children adopted worldwide. That only lessened in the late 1980s after Korea began limiting the number of children who could be adopted out of the country.

And many had tried without success to find anything about their families. Some just wanted to connect with their Korean roots. International Adoptions in the United States didn’t begin in earnest until 1955 and the passage of the Bill for Relief of Certain War Orphans. At first, the large-scale international adoptions were from Korea coming just after the Korean War. For at least 40 years, most international adoptions originated in Korea, with at least 200,000 children adopted worldwide. That only lessened in the late 1980s after Korea began limiting the number of children who could be adopted out of the country.

Coming from Korea

Thomas was part of that initial wave of early adoptees from Korea. He understands why making those connections is so important for some adoptees. Some of it is simply wanting to connect with a biological relative. Still, it can also be about making cultural connections.

For whatever reason, he didn’t have the same tug to find his birth parents. He was happy with his adoptive family. His father once said to him that “you adopted us.” As Thomas remembers things, he had awful grades and was mostly non-verbal as a kid. He thought he was stupid. But he loved to invent and tinker.

Moving Forward and then Looking Back

After college at Purdue studying electrical engineering, Thomas worked first in communications equipment manufacturing and then moved into building medical devices. In the late 1980s, he founded his own company Mectra Labs. The company has built various laparoscopic surgical instruments used in cancer treatment as well as instruments for cardiovascular and brain surgeries. Thomas holds more than 40 patents.

He’s written two books about his life, The Unforgotten War from 1998, and his 2012 memoir Dust of the Streets: The Journey of a Biracial Orphan of the Korean War. As his career advanced, Thomas found time to give back to various causes and charities.

Mixed Roots

One of the many groups he helped was the Mixed Roots Foundation, a non-profit to help adoptees with multicultural backgrounds and their families through all adoption stages. Clement served on the board of directors for the foundation and, at one point, was given a 23andMe kit from the founder and president of the group, Holly Choon Hyang Bachman.

He thought he might as well try it. He was curious about the health results and looking at his 23andMe ancestry reports, he discovered that half his ancestry was Ashkenazi Jewish. After opting-in to DNA Relatives, Thomas looked at his results and found that he had hundreds of matches with other 23andMe customers who also opted into the feature. One of them was Holly.

“I had long since accepted the fact that I would never know one blood relative,” Thomas said.

And then he had 1,000.

“I might not have tested if Holly hadn’t given me the kit, so that’s why I started the free kit program,” he said.

Learning about Himself

He not only gave kits to Korean adoptees, through a Facebook group called Korean American Adoptees but also former service members who served in Korea interested in finding children they may have fathered.

Holly was the first biological relative he ever knew. But there would be more.

With help from his friend Bella, who works with the non-profit 325Kamra, which uses DNA testing to reunite Korean adoptees with their biological relatives, Thomas was able to find his half-sister and two half-brothers on his father’s side. And he identified his birth father, but he wasn’t able to meet him before he died. Thomas said he didn’t want to disrupt their lives. When his half-sister told him that her mother would be devastated by learning that her husband had fathered another child, Thomas backed off. But not before learning a little bit about his birth father and seeing photos of him. They shared a lot of interests. Like Thomas, he’d been a bit of a renegade, a tinkerer, engineer, who loved cars and animals. The two had a similar body type, and although Thomas didn’t see it, his sister said Thomas looked a lot like his birth father.

“It was fascinating to hear about how he was as a person because when someone was describing him, I thought they were talking about me,” he said.

It’s been a gift to learn about his birth father in this way, and he feels fortunate that he’s helped others make similar connections.

“I mean, the stories just go on and on,” he said. “I didn’t realize the emotional aspect of this program … It’s a humbling experience.”