One of 23andMe’s newest scientists, Adam Auton, had his first day on Monday, and by Wednesday had two new  papers on human genetic variation published in the journal Nature.

papers on human genetic variation published in the journal Nature.

Not a bad first week of work.

“It’s been a busy few days,” Adam said.

The research on the papers was not done at 23andMe, of course, but it adds some important tools for scientists working here and elsewhere studying human genetic variation.

The papers actually cap eight years of work by the 1000 Genome Project Consortium, which over that time collected sequence data, exome and other genetic data to catalog genomic differences among people and in turn offer up those reference datasets for researchers studying the genetics of disease, traits and other conditions.

In the end the consortium, which included scientists from all over the world, sequenced the genomes of more than

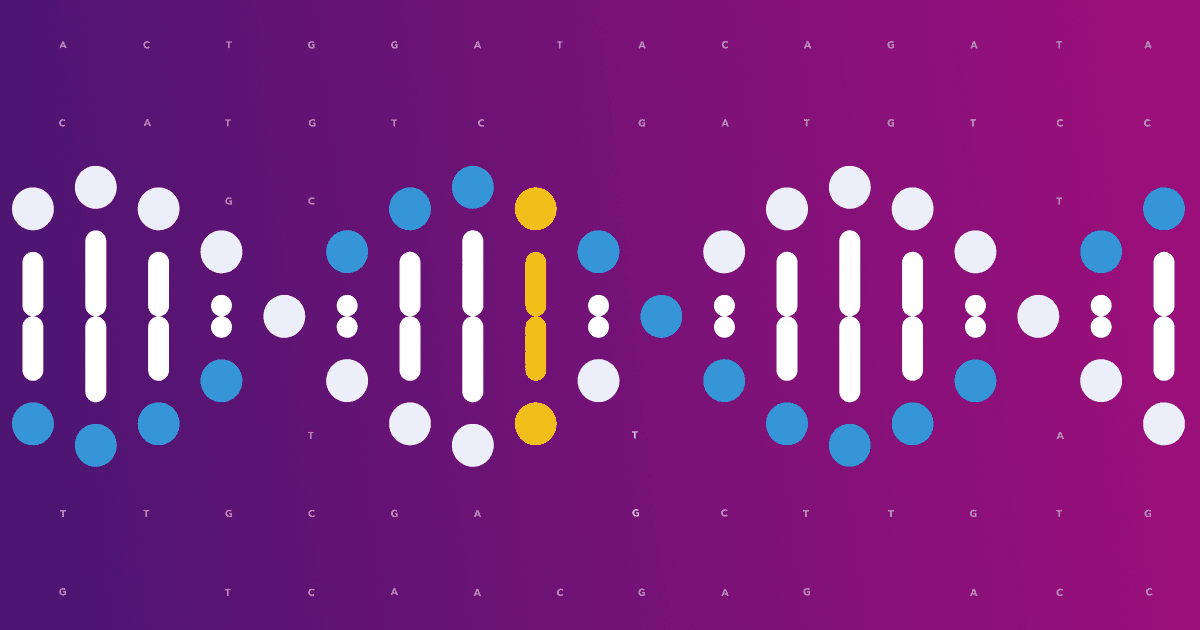

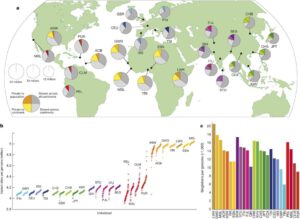

Population sampling illustration from the paper in Nature. This shows the variation within different global populations. African populations have the most variation among all populations in the world.

2,500 people from 26 populations worldwide. The final papers from that effort have just been published, and Adam was senior author of the main study paper. The effort created a new and more robust reference for human genetic variation, and mapped the structural variants among those reference populations. It is now the largest publicly available catalog of human genetic variation in the world.

“The project has been an international effort to build a reference dataset of genomic variation,” said Adam, who before joining 23andMe was an Assistant Professor of genetics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. “It really tells us about the structure of human genomic variation and diversity.”

Humans are almost 99.9 percent similar genetically, but because the genome is so vast that small genetic variation makes all the difference. Of the roughly 3 billion base pairs, differences are found in somewhere between 4 and 5 million locations. Percentage wise it is very small, but it’s enough to make a big impact, and learning more about where people and populations differ genetically can give us much more insight into the genetics of disease.

The project – more than 400 other scientists also worked in some form on the research – found about 88 million sites in the human genome where there is significant variation. That’s about 40 percent more variants than were previously known in humans, according to the researchers. Many of those sites likely have no significant impact, but others do and they may help researchers looking at both common and rare diseases, as well as other human traits.

For Adam what’s most interesting is what comes next.

It’s now 25 years since the Human Genome Project, but it’s really only in the last five to ten years that we’ve had the robust technologies to truly “do genomics,” Adam said.

“The 1000 Genome Project has laid the foundation for others to answer really interesting questions.”