By Janie F. Shelton, Scientist, Data Collection at 23andMe

Being hungry doesn’t put anyone in a good mood, but have you ever felt hangry? “Hangry,” a mashup of hungry and angry, entered the popular lexicon in the 1990’s and was formally added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2018.

While this term describing the foul mood many of us experience when we’re hungry is relatively new, the connection between hunger and mood has been around for a while.

Hunger Pangs and Anger

Several studies have found that low blood sugar is associated with personality changes, including higher aggression between spouses.[1] In another study comparing judicial decisions by time of day, judges handed down harsher sentencing decisions before mealtime breaks compared with after.[2]

Feel an argument coming on? Try a snack first.

Up for trial? Bring the judge a sandwich.

Do You Feel Hangry?

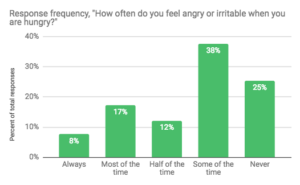

We asked 23andMe research participants to take a survey on eating behaviors, including the question, “How often do you feel angry or irritable when you are hungry?” (Fig. 1). Out of over 100,000 people who answered the question, 75 percent said they felt “hangry” at least some of the time.

Figure 1. Response frequency to the survey question “How often do you feel angry or irritable when you are hungry?” Possible responses were “always”, “most of the time”, “half of the time”, “some of the time”, and “never”. n=107,577.

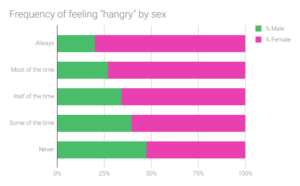

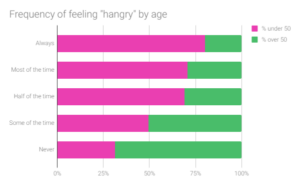

Responses varied significantly across sex and age. Women were much more likely than men to report feeling angry or irritable when hungry (Fig. 2). People under 50 were also more likely to report anger and irritability when hungry than those over 50 (Fig. 3).

The Genetics of Being Hangry, Like the Wolf

To investigate the underlying biology of feeling angry and irritable when hungry, we ran a genome-wide association study among unrelated Europeans, controlling for age, sex, genetic ancestry, and the version of genotyping platform.

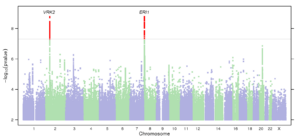

Two regions reached genome-wide significance, which are indicated in red in Figure 4. This graph is called a Manhattan plot, and it shows how strong the associations are between answers to the hangry

Figure 2. Percent of male and female respondents by category. Women were much more likely than men to report feeling angry or irritable when hungry.

question and different genetic variants (represented by dots). Red dots show genetic variants that are “statistically significantly” associated with getting hangry — which means they’re most likely to be real associations (as opposed to random noise).

One region was located in the vaccinia-related-kinase 2 gene (VRK2), and the other in the exoribonuclease 1 gene (ERI1). Both of these loci have previously been associated with a range of personality and neuropsychiatric conditions. Specifically, the VRK2 gene has been associated with schizophrenia,[3] depression.[4] epilepsy, and multiple sclerosis.[5]

In two publications using 23andMe data, ERI1 has been associated with subjective well-being, irritability, and neuroticism.[6],[7] ERI1 is a protein-coding gene associated with a known inversion

Figure 3. Percent of under and over 50 respondents by category. People under 50 were more likely to report feeling angry or irritable when hungry.

polymorphism on chromosome 8. An inversion polymorphism is a kind of genetic variant where a segment of the chromosome has broken off, flipped 180 degrees, and reintegrated in the same place. Inversion polymorphisms have a unique role in the genome because they are less likely to be altered through recombination across generations. This inversion is common, with an estimated frequency of 80 percent among Africans, 50 percent among Europeans, and 20 percent among Asians.[8]

Personality and Mental Health

Taken together, these results suggest that feeling angry and irritable when hungry may have origins in the genes that govern our personalities and mental health. While we initially expected feeling hangry to be more directly related to blood sugar regulation, these results are not a complete surprise because many of the genes involved in obesity implicate pathways that act in the brain.[9]

Figure 4. Genome-wide association study manhattan plot for “How often do you feel angry or irritable when you are hungry?” Possible responses were “always”, “most of the time”, “half of the time”, “some of the time”, and “never”. n=107,577. This model treated the responses as linear, and adjusted for age, sex, genotyping platform, and the top-5 principal components of genetic ancestry.

While feeling hangry might make you feel on edge, could it give you an edge? Before heading out to the halfpipe, the 2018 women’s snowboarding gold medalist tweeted, “Wish I finished my breakfast sandwich but my stubborn self decided not to and now I’m getting hangry”. She then proceeded to dazzle the world with her inverted 540 and double 1080’s, proving to the world that feeling hangry can’t stop you from becoming a world champion.

Footnotes:

[2] Danziger S et al. (2011). Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. PNAS. 108 (17) 6889-6892