Editors’ note: We first posted this piece by Joyce Tung, Vice President of Research at 23andMe, on April 4 2017, but in light of the current budget debate over deep cuts in federal funding for scientific and medical research, it seems appropriate to repost now. Joyce points out that investment in research and science innovation has distinguished the United States through history.

By Joyce Tung, PhD, 23andMe VP of Research

I love science.

I love how science requires a precision of interpretation, provides the thrill of discovery, and stimulates and satisfies curiosity all at the same time.

This is why I, like other scientists, have been dismayed each year by this administration’s proposed cuts in funding for basic science. Again this year the White House’s preliminary 2019 budget proposal calls for significant cuts to many scientific institutions or scientific programs in the government.

For the record, I understand no milk has actually been spilled yet. But I have the same sense of helpless foreboding I get when I see a toddler’s elbow approaching his cup of milk: at least some milk will be lost.

To propose cutting federal spending on scientific programs in such a significant and consistent way suggests that there are a lot of people who don’t value science and its principles of exploration and adherence to the data as much as I do.

So I felt like I needed to take a step back and ask myself if there’s a way to help show how important investment in science is to a broader audience. Fortunately, this has already been eloquently done back in 1945 by a man named Vannevar Bush.

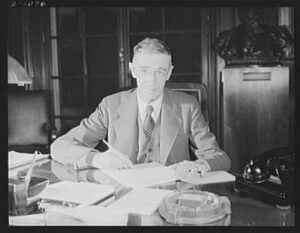

Born in 1890 in Massachusetts, Bush is known for contributing to or spearheading many scientific and technological achievements, including the differential analyzer (an early analog computer), the memex (conceptually a forerunner of hypertext), and the Manhattan Project. Photo: Library of Congress

The Endless Frontier

Bush was the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, which was established by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1941 to supervise important Allied research and development during World War II into efforts such as improving weaponry and medical treatments. After the war was over, in a letter to Bush, President Roosevelt requested Bush’s recommendations on how to keep the pace of scientific progress enjoyed during the war going in the United States. The resulting report compiled by Bush — Science, the Endless Frontier — was incredibly far-sighted and influential, and among other things led to the creation of the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Here are some of his words, with examples from my own experience becoming a scientist to help illustrate his points.

“The responsibility for the creation of new scientific knowledge — and for most of its application — rests on that small body of men and women who understand the fundamental laws of nature and are skilled in the techniques of scientific research. We shall have rapid or slow advance on any scientific frontier depending on the number of highly qualified and trained scientists exploring it.”

Investing in the Future

Scientific training can be a long and expensive process, taking anywhere from six to more than ten years post high school to complete. To encourage people to take that route requires support to extend the years of education. I was grateful to be supported by an NSF graduate research fellowship in graduate school and a training grant from the National Institutes of Health during my postdoctoral training.

I am not alone. Federal funding supports 15 percent of graduate students and over 50 percent of postdoctoral trainees in science, engineering, and health, according to 2015 NSF survey data. And the work that we do here at 23andMe to put out a high-quality, cutting-edge product is absolutely dependent on the talent that we are able to recruit.

“It is wholly probable that progress in the treatment of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, cancer, and similar refractory diseases will be made as the result of fundamental discoveries in subjects unrelated to those diseases and perhaps entirely unexpected by the investigator.”

The history of genetics leading to modern human genetics is a great example of these points. We learned basic concepts of inheritance by studying peas and flies and mice. This, along with basic efforts to understand the structure and function of this funny molecule called DNA, ultimately led to the current explosion in human genetics.

“One of our hopes is that after the war there will be full employment. To reach that goal the full creative and productive energies of the American people must be released. To create more jobs we must make new and better and cheaper products. We want plenty of new, vigorous enterprises. But new products and processes are not born full-grown. They are founded on new principles and new conceptions which in turn result from basic scientific research. Basic scientific research is scientific capital.”

Tomorrow’s Breakthroughs

Scientists are now applying the ideas we have learned from human genetics to developing new drugs, personalizing treatments for cancer, and empowering consumers with their personal genetic information. These innovations not only have the potential to improve human health, but are creating new jobs in new industries.

Science is wonderful not only because of all the useful things we’ve already learned, but because of all the things we have yet to discover. To continue to reap the economic, health, and quality of life benefits from the powerful system of scientific research we have in the United States requires continued investment. I hope that as a country we make the choice to continue to support basic science research and the next generation of scientists who will make tomorrow’s breakthrough discoveries.

Bush closed his report by saying,

“On the wisdom with which we bring science to bear against the problems of the coming years depends in large measure our future as a nation.”

The journal Nature has details on the proposed cuts here.