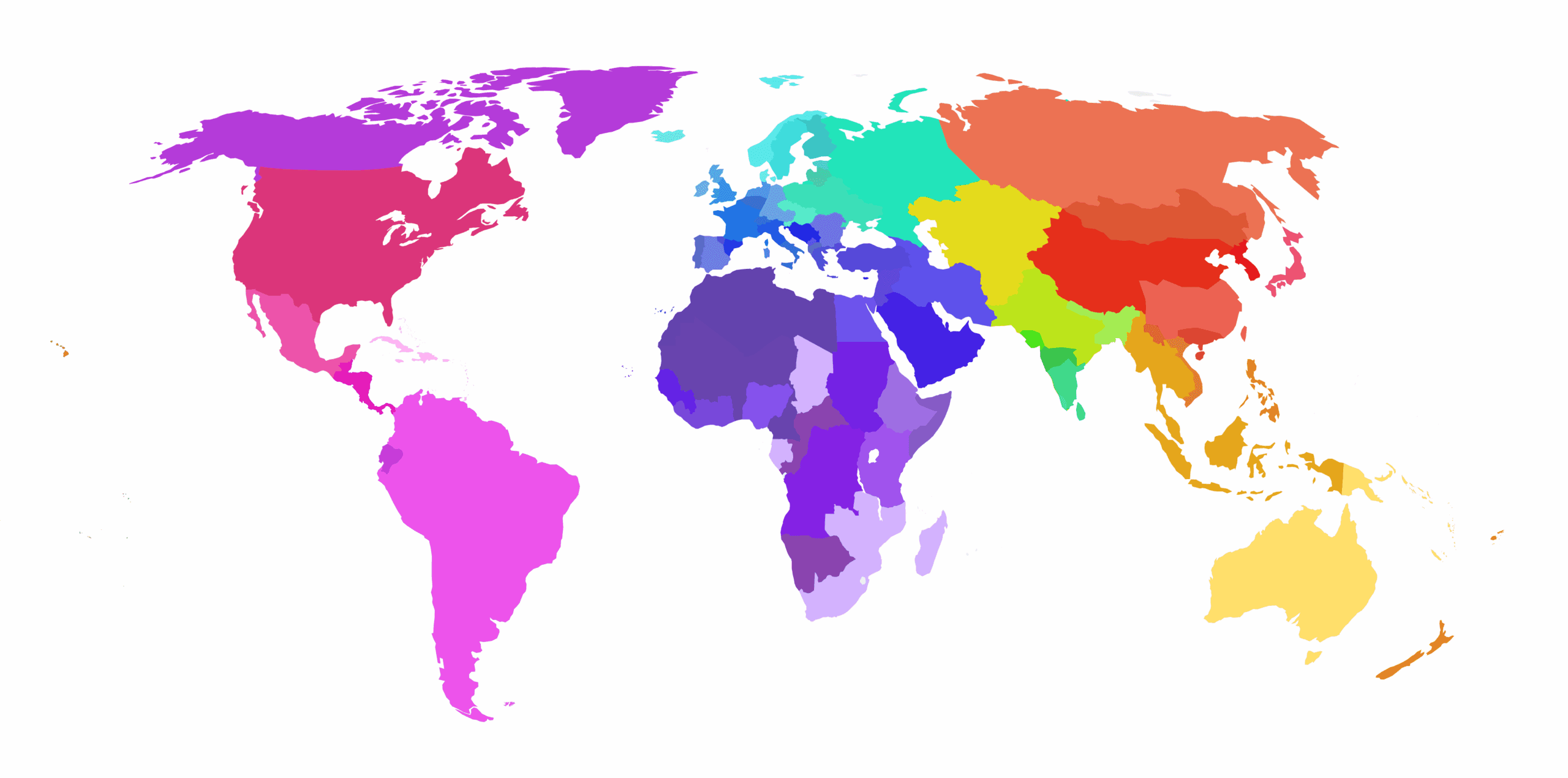

Throughout the history of our species there has been one constant: movement. Since the origin of Homo sapiens nearly 200,000 years ago in East Africa, humans have journeyed around the globe, ultimately inhabiting every continent save Antarctica.

Scientists have traditionally used archaeology, and more recently genetics, to understand the timing and scope of these ancient migrations. The field of historical linguistics has also been used in the same way, reasoning that if people migrated to new regions, they would have brought their languages with them. In this way, linguistics can be used as an additional resource in understanding our species’ past movements.

However, this concept is rarely — if ever — that straightforward. For example, a language might spread from local population to local population, while the original speakers of the language stayed put. This concept, called ‘cultural diffusion’ is at the core of many debates about our species’ prehistory: did people (and therefore their genes) migrate to a new region, or was it just a transfer of cultural traits (such as language) from one region to the next?

There are two famous examples in human prehistory that delved deep into this very question.

Bantu Expansions in sub-Saharan Africa

About 5,000 years ago, the majority of sub-Saharan African peoples still relied on hunting, gathering, and foraging as their main source of food. But some people in west-central Africa were developing new techniques of survival. They began to experiment with herding and agriculture, cultivating the yams, legumes, peppers, and gourds that would became staples of a sub-Saharan African diet. Then, about 4,000 years ago, they began to move. As they traveled over a period of centuries, they both displaced and absorbed groups that were already living throughout Africa.

The languages that they brought with them from their ancestral homeland, belonging to the Bantu family, also spread throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Today the majority of sub-Saharan African languages are Bantu.

What both genetics and linguistics have told us about the Bantu expansions is that it was an expansion of both peoples and cultures. Though these early Bantu speakers may have intermarried as they expanded, their genetic signature still shows West African ancestry. The distribution of Bantu languages throughout sub-Saharan Africa confirms this prehistoric migration. In fact, this example marks one of the most straightforward instances of a combined genetic and cultural expansion.

The Spread of Agriculture and Indo-European Languages

Unfortunately, the spread of agriculture from the Near East into Europe and its connection to the spread of Indo-European languages is far more complicated.

Agriculture is believed to have originated in the Near East about 13,000 years ago. Starting about 10,000 years ago, the archaeological record indicates that the practice expanded westward into Europe. By 9,000 years ago, agriculture existed in Greece. By 5,000 years ago it had reached Scandinavia.

But was this spread of technology accompanied by farmers themselves, as in the Bantu migrations? Linguists felt they had the answer: the vast majority of languages spoken in Europe today are members of the Indo-European language family. Languages such as Greek, Latin, Celtic, and English all belong to this group. In fact, only a few isolated European languages (such as Basque and Finnish) are unrelated.

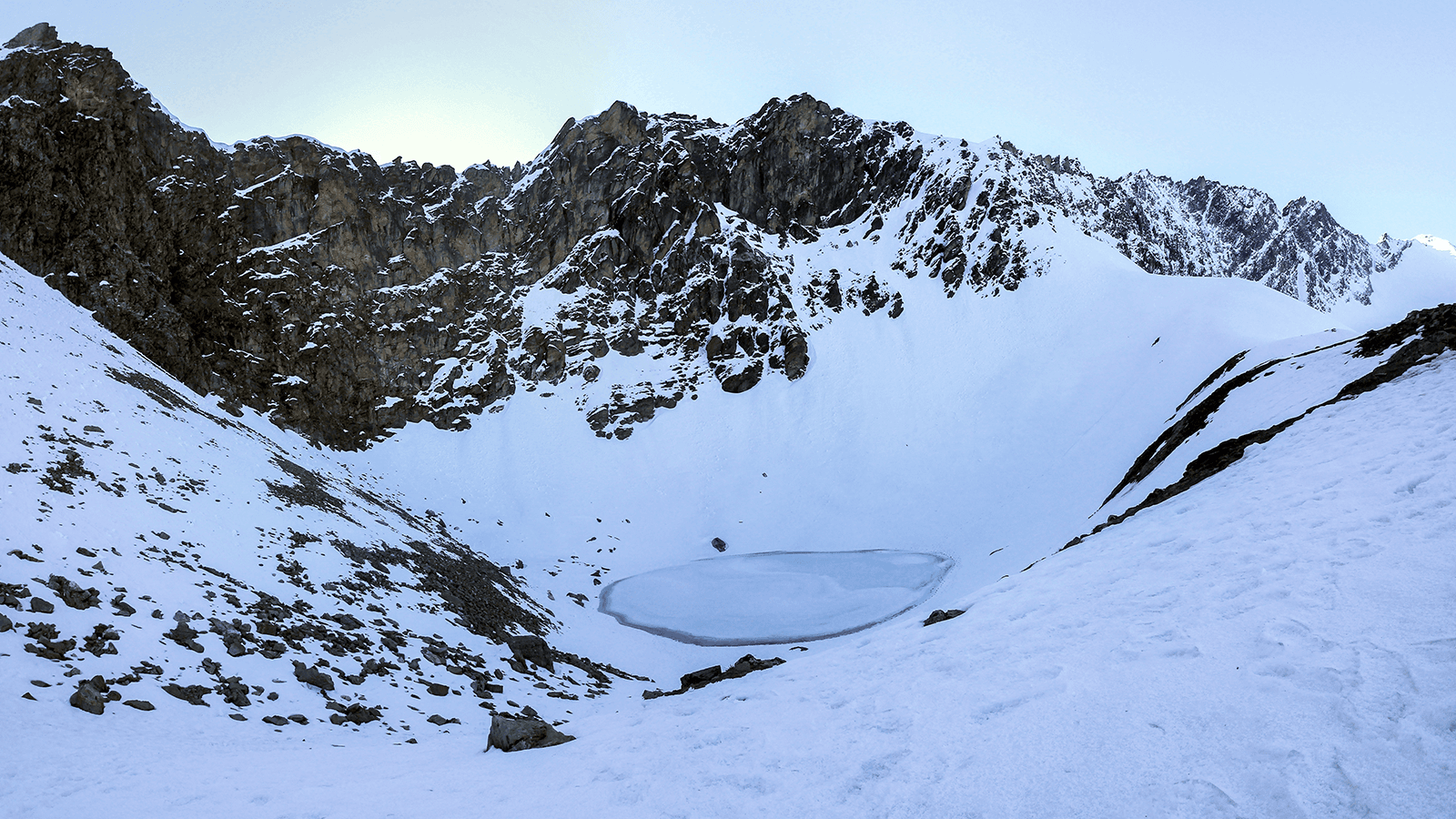

Linguists argued that the geographical origin for this language family was probably somewhere in the Near East or Caucasus Mountains, and that these languages spread — along with the farmers themselves — into Europe, replacing the older languages that were already in existence. The archaeology appeared to support this idea, and soon many scholars had argued for an expansion of agriculturalists from the Near East.

However, the genetics told a somewhat different story. Though there are genetic footprints in Europe of these early Near Eastern agriculturalists, there are pre-agricultural genetic footprints as well. In fact, more Europeans trace their ancestry back to ancient European hunter-gatherers, who survived the harsh Ice Age in the southern fringes of Europe 20,000 years ago, expanding into northern Europe as glaciers receded several thousand years later. They were not replaced or marginalized by the arrival of agriculturalists.

This discordance has made the question of the arrival of agriculture and Indo-European languages in Europe one of the most contentious in the fields of archaeology, genetic anthropology, and linguistics. It remains unresolved, though many scientists now argue for lower levels of genetic diffusion into Europe than originally thought.

There are countless other examples in human prehistory of cultural vs. genetic diffusion, with different disciplines often yielding different hypotheses. The connection between genetic diffusion and cultural diffusion is anything but straightforward, and the best research will take into account not only genetic and linguistic evidence, but evidence from the archaeology, human skeletal remains, and paleobotany. As noted scientist and author Jared Diamond has put it, “It is quite a challenge, but a uniquely fascinating one.”