By Samantha Ancona Esselmann, Ph.D., and Chelsea Robertson, Ph.D.*

Editor’s note: A version of this post originally appeared earlier this year in our premium content for 23andMe+ members. We are reposting it on 23andMe’s blog for Pride Month. In this article, the term “sex” is used in a developmental and biological sense. This article does not focus on sexual orientation or gender identity, which were addressed in a previous blog post.

A shallow understanding of the mechanisms that determine biological sex might lead one to suppose that sexual development is a simple matter of reading the same recipe and always ending up with the same cookie. It’s not.

We are astonishingly complex bags of organic and inorganic chemicals that defy entropy until we die. You can change the recipe and end up with the same cookie, or follow the same recipe and end up with a completely different cookie. (And, if baking were easy, we wouldn’t have just finished the 10th season of the “Great British Baking Show.”)

Infinitely more complicated than baking a 20-layer Schichttorte are the biological processes that determine your sex. Your sex, like Schichttorte, has a lot of layers.

At the bottom, there’s your chromosomal and genetic sex. There are also sex organs, hormones, and secondary sex characteristics — like beards and breasts. Then, of course, there’s your biggest sex organ, your brain, wherein an incomprehensibly large ensemble of neurons shout, whisper, and sing a symphony of sexual identity that is wholly unique to you.

And while all those layers can be consistent with a binary definition of sex, sex is not binary: Any one of the layers can be swapped out for a different color or texture, or taste. Humans can be intersex.

In a recent 23andMe blog post about sex and gender, Dr. Jey McCreight explained, “at least one in 1,500 births are intersex, meaning that a person’s anatomy and/or their chromosomes can’t be classified as typically male or female. This is a conservative estimate, as many people do not realize they are intersex until later in life. Some never find out.”

Let’s start at the very beginning.

The sex gene

During the first few weeks of your life, you were an androgynous mass of cells. In form and face neither male nor female nor even recognizably human, you followed an age-old sequence of gestational milestones, starting with important ones like, “Grow heart!”

As you bobbed and rolled, tethered to life by a spongy tube full of filtered blood, the cells of your primordial gonads still existed in a bi-potential state, meaning they possessed the power to develop and multiply into either ovaries or testes.

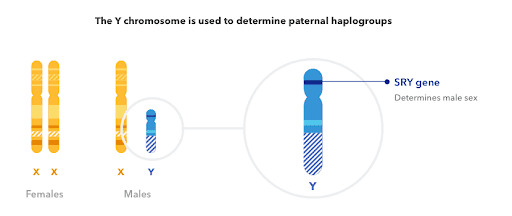

Which path these cells eventually followed depended on either the absence or the activation of a gene located on the Y chromosome. That gene is called SRY, or the Sex-determining Region on the Y chromosome… a very un-sexy name for the “sex gene.”

In the absence of SRY activation, the default human embryo is female. But, turn on that switch and, like a soupy Rube-Goldberg machine, a fractal cascade of carefully orchestrated chemical events is initiated, knocking that developing embryo onto a “male” path. This path is not simply a matter of making all the male bits. It also requires a manual override of ovarian development — an active silencing of the default human protocol.

Needless to say, there’s a vas deferens between these two paths.

Chromosomes and sex

Through services like 23andMe, people may learn that their chromosomal sex doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth. We all fall on slightly different points along a spectrum between typical biological female and typical biological male, but most of us go through life without ever knowing the exact complement of chromosomes in our cells.

You need at least one X chromosome to survive past the tumultuous early days of embryonic development. But beyond this most basic requirement, there’s a lot of wiggle room in the pantheon of chromosomal sex.

Generally, people with no Y chromosome appear biologically female, while people with at least one Y chromosome appear male: Most females are XX, and most males are XY. But there are other combinations too, such as XXX, XXY, XYY, XYYY, XXXY, XXXX, X (also known as XO), and mosaic XY/X or XX/X individuals, whose unusual karyotypes arose from a failure of sex chromosomes to end up in the right place during cell division. (A karyotype is the number and appearance of your chromosomes under a microscope.)

But, your sex isn’t only about which sex chromosomes you have.

More on chromosomes: Why it’s not all about the Y

Over tens of millions of years, the Y chromosome’s role in humans has atrophied to one of ferrying a few genes across the generations to enable us to reproduce sexually.

But, it’s possible to have a Y chromosome and be genetically female, hormonally female, and physically female (meaning you have a Y chromosome but lack a functioning SRY gene). It’s also possible to lack a Y chromosome and be genetically, hormonally, and physically male.

These situations typically arise in a father’s sex cells when there’s a mutation in the SRY gene, or when SRY jumps from a Y chromosome onto an X inside a sex cell — rendering the former almost completely vestigial and conferring the power of sex determination on the latter.

When an SRY-deficient Y chromosome is passed on, the sexual development of the XY fetus can follow a similar path to that of a fetus without a Y chromosome. The other side of the same coin can mean that there are XX males who inherited an SRY gene on an X chromosome. There’s even a report of a male with two X chromosomes who lacks the SRY gene, and scientists speculate that mutations in other genes related to sexual development can also promote masculinization.

And, well, biological sex doesn’t exactly get less complicated from here.

Beyond SRY, sex determination and development also depend on a flurry of hormones that help direct and monitor the progress of the human build, from gestation to adulthood.

Hormones

Hormone signaling in the womb affected the progress of your sexual development and, in particular, the shape and formation of your external genitalia — the appearance of which had a big impact on the sex you were assigned at birth.

The assignment of a baby’s biological sex is rarely called into question when the infant’s genitalia appear “normal” or as expected. But by this point, you can probably guess, biological sex is not as simple as what’s visible in your nether regions.

Certain genetic variants affecting hormone production and signaling can have dramatic effects on the formation of genitalia in the womb. So while you can be XY or XX or X (XO), or any other combination, small changes in hormone production and signaling can push you in different directions along the spectrum of biological sex traits, much like how small changes in humidity or temperature can change the rise of your bake.

Got a variant that boosts your testosterone levels? Might not be noticeable if you are a male (XY) embryo, but XX females with a variant like this may have genitalia at birth that do not appear particularly male or female.

Got a variant that changes the way testosterone transmits signals to the cell? If you’re a female (XX) embryo you might not have any noticeable signs or symptoms at birth. But if you’re a male (XY) embryo, your genitalia may appear more ambiguous.

What about when babies are born with the expected external genitalia, but nevertheless have differences in hormone production and signaling? Sometimes hormonal differences go largely unnoticed until the early teenage years when your hormones return to center stage in Act 2 of your sexual development — puberty.

Got a genetic variant that inhibits the production of testosterone? If you are a male (XY) embryo, it’s possible that your genitalia could appear female at birth. You could be raised as a female for over a decade, then puberty hits and your body doesn’t do the normal female puberty thing. Instead, you notice increased muscle mass, some facial hair, and a deeper voice.

So you can be XY, insensitive to the effects of testosterone in the womb, born with female genitalia, then go on to develop male secondary sex characteristics later in life.

Are the lines encircling the concepts of biological sex beginning to blur?

Let’s recap.

You can be chromosomally and genetically male or female, but depending on your particular hormone production and signaling systems, you might end up somewhere else on the spectrum of biological sex.

Hormonally and physically, you can be somewhere in between male and female.

So why does this matter?

Imagine, for a moment, how boring life would be if every baguette came out of the oven the same, or if every birthday cake had the same frosting, or the same filling. The more we understand about the textured, richly flavored layers of sexual development, the better equipped we are to mobilize empathy for others and their diverse experiences.

*Both Samantha and Chelsea are 23andMe Product Scientists, and both hold doctorates in neuroscience.

- Rey R, Josso N, Racine C. Sexual Differentiation. [Updated 2020 May 27]. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., editors.

- McCreight, J. 2020. “Celebrating Pride Month, a Spotlight on Sex and Gender.” 23andMe blog.

- Bachtrog D. (2013). “Y-chromosome evolution: emerging insights into processes of Y-chromosome degeneration.” Nat Rev Genet. 14(2):113-24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23329112/

- The Y chromosome is disappearing – so what will happen to men? by Darren Griffin, The Conversation. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://phys.org/news/2018-01-chromosome-men.html

- Montañez A. (2017). “Beyond XX and XY.” Sci Am. 317(3):50-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28813372/

- Gomez-Lobo V et al. (2016). “Disorders of Sexual Development in Adult Women.” Obstet Gynecol. 128(5):1162-1173. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27741188/

- Ha NQ et al. (2014). “Hurdling over sex? Sport, science,nd equity.” Arch Sex Behav. 43(6):1035-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25085349/

- MedlinePlus (2019, Aug 7). “Intersex.” Retrieved October 31, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001669.htm

- MedlinePlus (2010, Feb 1) “CYP21A2 gene: Health Conditions Related to Genetic Changes.” Retrieved October 31, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/gene/cyp21a2/#conditions.

- MedlinePlus (2018, Sept 1)“Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to 11-beta-hydroxylase deficiency.” Retrieved October 31, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/congenital-adrenal-hyperplasia-due-to-11-beta-hydroxylase-deficiency/

- Ohnesorg T et al. (2014). “The genetics of disorders of sex development in humans.” Sex Dev. 8(5):262-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24504012/