Treatment advances have dramatically increased the cure rate for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common diagnosed cancer in children, from less than 10% in the 1960’s to more than 80%.

But even in those children who are cured, the response to treatment varies from patient to patient. For some, just a couple of weeks of chemotherapy can drastically reduce the number of leukemia cells in their bone marrow, while others continue to have high levels of disease even after six weeks of intensive therapy.

Now, researchers have discovered that these differences may depend on a patient’s genetics.

Much of the previous work aimed at understanding the variability in responses to cancer treatment has focused on differences between the cancer cells themselves. But researchers from St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital and the Children’s Oncology Group have taken a different approach, focusing on genetic variations inherent to the cancer patients and present in all cells of their bodies.

“Although the acquired genetic characteristics of tumor cells play a critical role in drug responsiveness, our results show that inherited genetic variation of the patient also affects effectiveness of anticancer therapy….Such variation may be factored into treatment decisions in the future,” the authors write.

Their study, published online yesterday the Journal of the American Medical Association, identified more than 100 SNPs linked to the number of leukemia cells that survive after initial treatment. A significant number of these same variations were also associated with early response, relapse and drug metabolism.

Children receiving different types of chemotherapy were studied to increase the chances that the SNPs identified by the study would be associated with treatment response in general, and not just response to a specific drug. A total of 487 kids, each receiving one of three different treatment regimens for ALL, were genotyped at more than 400,000 SNPS.

In all, 102 SNPs were associated with “minimal residual disease” (MRD), a measure of the number of leukemia cells that survive after the initial phase of treatment. Some of these SNPs are very close to each other and are likely markers of the same effect, but the researchers say that they identified 72 unique regions of the genome associated with this trait.

There are differences in ALL prognosis between different racial groups. For example, African American children have been shown in some studies to have lower survival rates than white children. The researchers suggest that this could be due to differences between the two groups in the frequency of the protective versions of SNPs identified in this study. In the future, the researchers write, findings like theirs could lead to “race-neutral” treatment decisions that are based on an individual’s unique DNA make-up instead of unreliable assumptions based on ancestry.

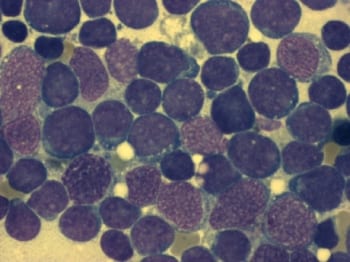

Photo of bone marrow cells from an ALL patient by Furfur.