By Samantha Ancona Esselmann, Ph.D., a 23andMe Ancestry Product Scientist

The genetic ancestry testing industry† is younger than Facebook.

Since the mid-aughts, around 35 million people have “done their DNA,” and as we chew on our own results, the industry struggles to keep up with an evolving understanding of identity in a genomic era. There’s a lot of learning and adjusting that’s happening in real time.

I’m still learning, too.

I’ve learned that it’s essential that Direct-to-Consumer DNA testing companies be clear about the differences between DNA, ancestry, and identity. And, for this Native American Heritage Month,‡ I decided to share what I’ve learned about how these concepts impact not only the lives of Indigenous American individuals but also the sovereignties of Indigenous Nations.

Identity is complex, and the discussions raised in this post are intended to amplify the perspectives of individuals from North America with Indigenous ancestry. In Mexico, Central America, and South America, Indigenous ancestry is more common than in North America, and their perspectives on how DNA does or does not relate to cultural identity are distinct. Furthermore, the adoption of Indigenous children presents a different set of issues related to identity and ancestry that are not explored here.

Whether or not you have “Native American DNA,” it’s essential to understand what it means — and doesn’t mean — to find evidence of this ancestry in your DNA.

What it does mean

- With some degree of statistical confidence, some sections of your DNA match a limited set of Indigenous American reference individuals more closely than they do other global reference populations.

- Suppose information about a possible Indigenous American ancestor is new to you. In that case, you can be excited about this ancestry and use it as a starting place to learn more about the diverse Indigenous histories of the Americas respectfully. However, your test result should be viewed cautiously in the context of the technology’s limitations.

What it does not mean

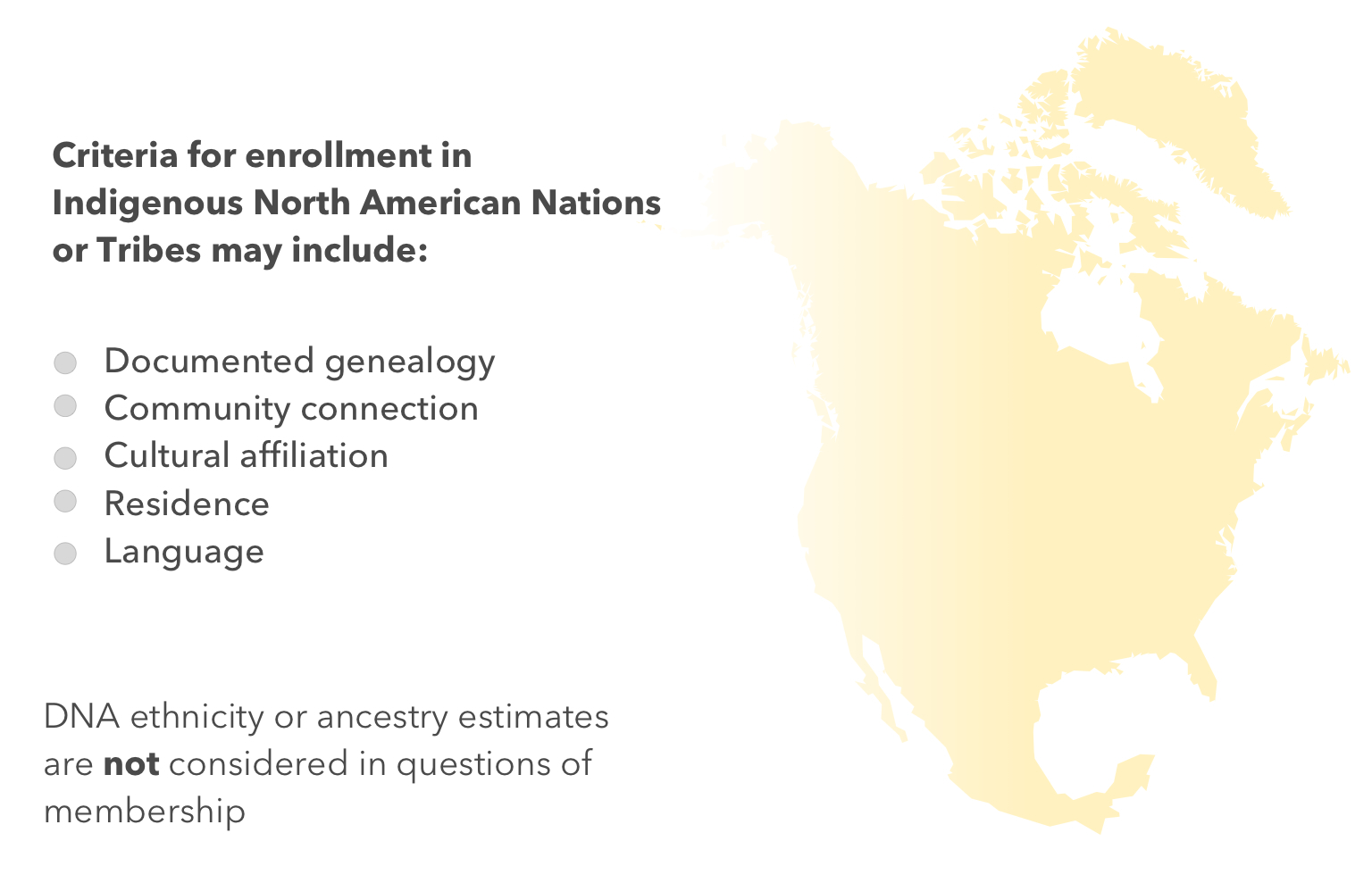

- You cannot use these results to seek or confirm membership in a Tribe or Nation. These tests simply do not provide enough information to confirm this kind of affiliation. Tribal enrollment processes use genealogical evidence of kinship, not genetic ancestry test results.

- It doesn’t mean you should start identifying as Native American based on the results of a genetic ancestry test.

- It doesn’t mean you can claim Native identity and then use genetic ancestry testing to “confirm” it.

- It doesn’t mean you can go to your Native American friends and say, “Hey, guess what? I took a DNA test, and it turns out I’m Native American, too!”

Keep in Mind

If that last point is confusing, perhaps you have a frame of reference that can help you empathize: Would it rub you the wrong way if someone who never lived in your hometown told you they identified as being from there?

Being Native American isn’t just about having Indigenous American ancestry. It’s about being part of a culture…part of a community with shared beliefs, histories, and experiences. And no matter where you’re from, biology is ultimately not how group membership is determined.

Just as countries outline their own processes for obtaining citizenship, many Indigenous North American Nations, Tribes, or Bands determine enrollment based on many factors, such as documented descent from enrolled ancestors. While some Indigenous Nations have used DNA to ascertain close familial relationships (e.g., paternity tests), genetic ancestry estimates like those conducted by 23andMe are not used to determine enrollment.

Cultural Connections

Today, many people with Indigenous American genetic ancestry have no cultural connection to Native communities.

Today, many people with Indigenous American genetic ancestry have no cultural connection to Native communities.

There has been a centuries-long, systematic erasure of Indigenous Americans that began with slaughter and continued through the 20th century in the form of cultural assimilation. In North America, the U.S. and Canadian governments partitioned Native lands, incentivized Native people to relocate to cities, and compelled Native families to send their children to residential schools far from home, where diseases spread like wildfire, abuse was commonplace, and expressing one’s Native culture was forbidden. For many, the psychological wounds of these institutions are still raw: the last residential school in Canada closed in the 1990s, and many boarding schools continue to operate in the U.S., though attendance is no longer mandatory.

Identity

Around one million 23andMe research participants, including many who don’t identify as Indigenous, have evidence in their DNA of having an Indigenous American ancestor.

In 2015, 23andMe published a study showing that over 5% of our research participants who identify as African American have at least 2% DNA predicted to most closely match an Indigenous American reference population (and 22% are estimated to have at least 1% of this DNA). While self-identified European Americans are generally less likely to have Indigenous American genetic ancestry, the numbers vary widely from one state to the next: as many as 8% of European American customers from Louisiana carried at least 1% of this genetic ancestry.

The Unexpected

Many of our customers expect to see evidence of Indigenous American ancestry in their DNA but don’t.

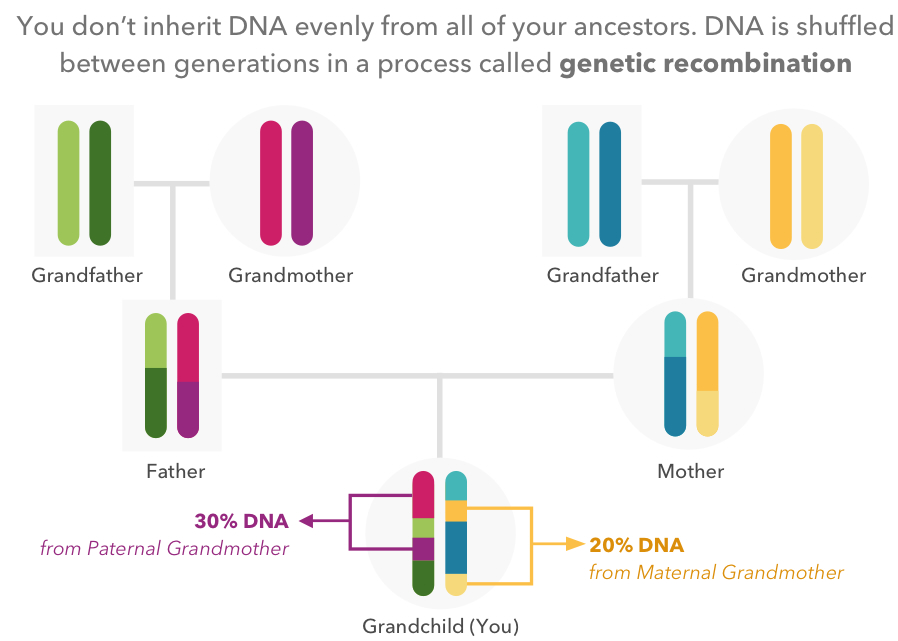

This is among the most common customer complaints we receive, and there are a few reasons why this could happen. As a result of genetic recombination — the process through which DNA is randomly shuffled between generations — the further back in your family history you look, the less likely you are to have inherited DNA directly from every single one of your ancestors. For example, there’s a roughly 5% chance that you inherited zero DNA from a 5th-great-grandparent.

This means that you can be directly descended from someone indigenous to the Americas without having any DNA evidence of that ancestry.

Family Stories

But, there’s another reason someone might not have “Native American DNA”: In North America during the 19th and 20th centuries, white settlers or their descendants sometimes misattributed an ancestor as Indigenous. This may have been to justify a more native-born “Americanness” or to absolve one’s family of blame for colonialism, and these stories are still passed down through families to this day.

If your family has a story like this but no documentation, it doesn’t necessarily mean those stories are wrong and don’t make you a bad person.

The takeaway

Whether or not you have “Native American DNA,” your genetic ancestry may not be consistent with your cultural identity. You can celebrate and reflect on what your results can tell you about your genetic ancestors but understand that falsely claiming a romanticized Native identity based only on that evidence can be deeply offensive to people whose identities, experiences, worldviews, and cultures are shaped by being Native American. Its cultural appropriation stems from colonialism.

I leave you with this: Indigenous peoples are modern peoples

It’s a simple but essential point.

While it may be easy for you to think of Indigenous peoples as living in the past or to imagine them only in their ceremonial regalia, festooned with intricate beadwork or wearing elaborately feathered headgear, this perception of them does not capture the whole picture of who they are and how they think of themselves today.§

Learn About Indigenous Culture

There are countless respectful ways you can engage with Indigenous cultures, and here are just a few:

- Experience Native Land — a resource that “creates spaces where non-Indigenous people can be invited and challenged to learn more about the lands they inhabit, the history of those lands, and how to actively be part of a better future going forward together.”

- Follow Indigenous creators on Instagram or TikTok (start by exploring #Indigenous or #Native hashtags).

- For Native American heritage month, Amazon Video and PBS are highlighting movies and documentaries featuring Native American voices.

- Read the work of the incumbent United States Poet Laureate, Joy Harjo, an enrolled member of the Muskogee Tribe.

- Browse online exhibitions at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian

- Check out the 45th annual American Indian Film Festival, which ran November 6 – 14, 2020, or attend the Native Cinema Showcase November 18 – 27, 2020

To dig deeper into this topic, I recommend reading “Native American DNA: Tribal Belongings and the False Promise of Genetic Science” by Kim TallBear.

Have other resources? Share them in the comments below.

Thank you to all of you who continue to grow and learn with us, and thank you for being passionately curious about the world and the diverse stories of the people close to you and those further away.

*Did you notice that “Native American DNA” in the title of this piece is in quotes? Krystal Tsosie, a Navajo (Diné) geneticist and bioethicist at Vanderbilt University explains why the phrase is problematic: “It biologically reifies the idea that DNA can be intrinsic to an ethnic group.” Additionally, the term “Native American” is considered U.S.-centric (First Nations people of Canada do not refer to themselves this way), and the phrase is rooted in colonialism: “America” comes from Amerigo Vespucci, an Italian navigator and merchant. For these and other reasons, Tsosie emphasizes, “We, as Indigenous scientists, use the term “Native American DNA” to highlight these limitations, but do not consider it a legitimate phrasing.” In this post, the terms “Native” and “Indigenous” are used interchangeably, and “Native American” is the name 23andMe has used for its reference panel for the Americas to date.

† In 2007, 23andMe became the first autosomal genetic ancestry test available to consumers. However, limited Y chromosomal and mitochondrial DNA analyses were available to consumers before 2007.

‡ Native American Heritage Month is celebrated during November in the U.S. Canada celebrates National Indigenous History Month in June.

• Even indigeneity is a modern category and people may not understand themselves in this way. For example, modern “Indigenous” Europeans would most likely identify as “European” rather than “Indigenous European.” Colonialism has forced such distinctions between Indigenous peoples and settler colonizers.