Last week, a new ancient DNA study led by researchers at the Max Planck Institute in Germany and the Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia in Mexico revealed that contrary to some early theories about ritual sacrifice practices in the ancient Maya civilization, not all sacrifice victims were young women.

In the study, the authors analyzed DNA from the remains of 64 sacrifice victims found nearly 60 years ago in an underground cistern in Chichén Itzá, an ancient Maya city in what is now Yucatán, Mexico. Buried between 500 – 900 CE (a time when Chichén Itzá was the most powerful city in the northern Maya region), the victims were children at the time of their death. To the researchers’ astonishment, every single one of the children had a Y chromosome, meaning that they were all genetically male. Not only that, many were siblings or cousins, and there were even two pairs of identical twin boys.

The El Castillo step-pyramid at Chichén Itzá.

Why twins?

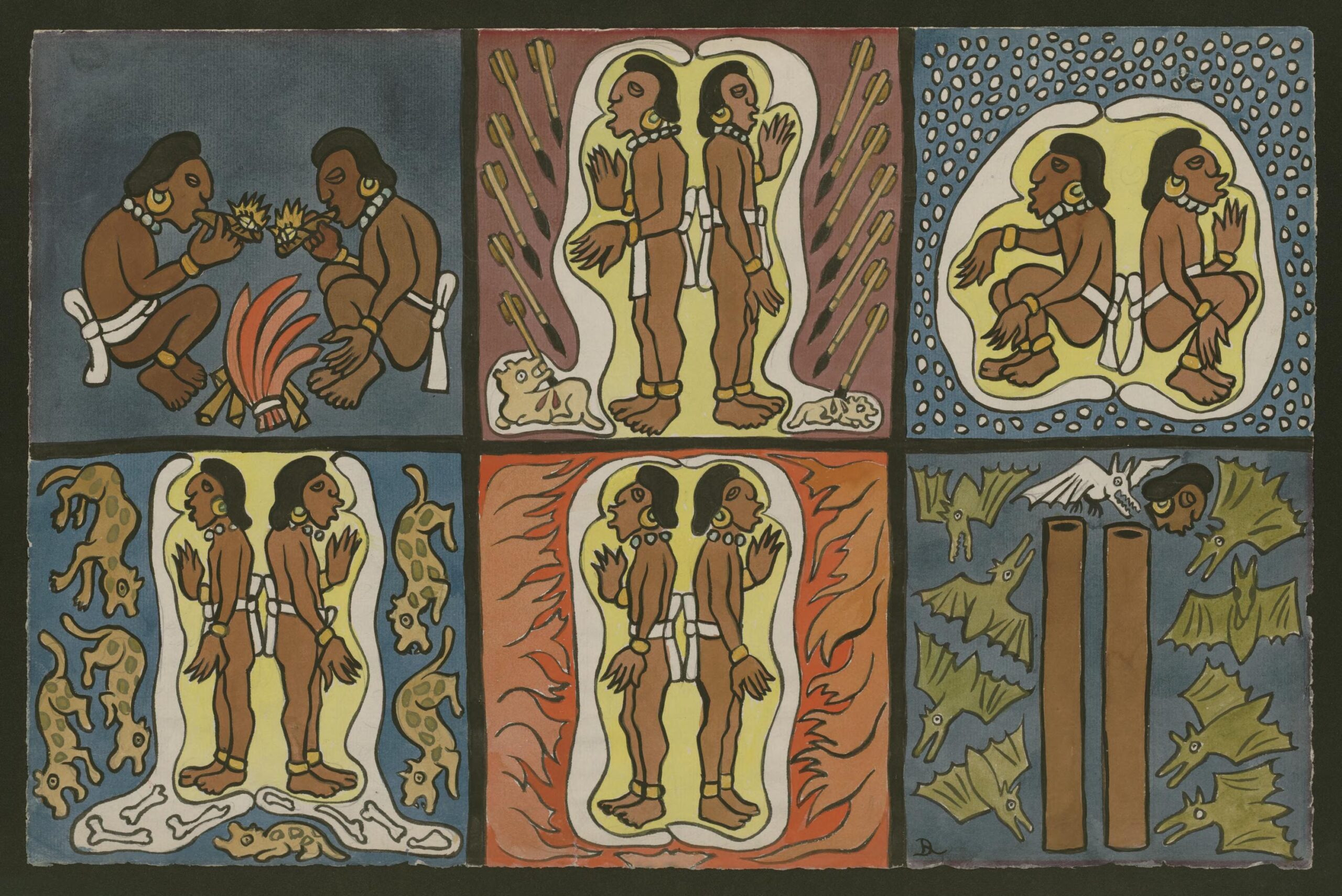

In Maya mythology, twin boys figure prominently. The story of Hero Twins Hunahpu and Xbalanque is chronicled in the Popol Vuh (or Popol Wuj), the Maya story of creation. In this epic, the twins are challenged to a series of tests by the Death Lords of the Underworld, Xibalba. Eventually, the twins outwit the crafty Death Lords and ascend to the sky to become the sun and moon. Researchers speculate that the story of the Hero Twins may have inspired the ritual sacrifice of the boys at Chichén Itzá.

“Trials of the hero-twins,” painted by Diego Rivera in 1931

Discovery of the mass grave

In 1967, workers who were building an airport runway near Chichén Itzá discovered the remains of over 100 children near Chichén Itzá’s Sacred Cenote (sinkhole) in a type of underground cistern called a chultún, which may have represented an entrance to the underworld.

Despite the site’s clear historical significance, archaeologists were granted only two months to excavate the site and exhume the bones so that they could be preserved and studied. Now, over 50 years later, ancient DNA technology has made it possible to learn more about the identities of the buried children.

The Sacred Cenote (sinkhole) which is located in the ceremonial center of Chichén

Find out if you are genetically connected

And the discoveries don’t stop there. Thanks to Historical Matches, SM our new 23andMe+® Premium membership feature, you can find out if you share a genetic connection with 24 of the sacrifice victims whose DNA was sequenced as part of this study (40 of the 64 genomes analyzed in the study did not meet 23andMe’s quality standards for inclusion in the feature).

Seven new Indigenous American Genetic Groups added in Mexico

In addition to adding the ancient Maya individuals from Chichén Itzá to the Historical Matches feature, we are also adding seven new Genetic Groups in what is now Mexico and parts of northern Central America, as well as a group in the Mariana Islands with Indigenous American ancestry introduced centuries ago as a result of Spanish colonialism. This update adds finer detail for customers with roots in these regions.

The update will be available for customers on the latest genotyping chip, V5.

Indigenous American Genetic Groups in Mexico, Central America, and the western Pacific

Below are the seven Genetic Groups we’ve added in the latest update.

Maya – Shared Indigenous American ancestors with people who identify as Maya in southern Mexico, Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, and western Honduras.

Mexican diasporic ancestry in the Marianas – Shared ancestors with people in the western Pacific who have Indigenous American ancestry that was introduced centuries ago due to Spanish colonialism. Most people in this Genetic Group identify as Chamorro—the Indigenous people of the Mariana Islands—and all carry a small amount of Indigenous American genetic ancestry, which was likely introduced to the Mariana Islands around the time of the Spanish–Chamorro Wars. The Indigenous American DNA in this Genetic Group is most similar to the DNA of people who identify as Otomí, who have historically resided in central Mexico, particularly around what is now Mexico City.

Purépecha – Shared Indigenous American ancestors with people identifying as Purépecha, primarily in Michoacán, Mexico. Today, the Purépecha mainly inhabit western Mexico, a community in Nicaragua that is believed to have descended from Purépecha migrants who settled in the region centuries ago.

Zapotec – Shared Indigenous American ancestors with people identifying as Zapotec, primarily in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Nahua – Shared Indigenous American ancestors with people identifying as Nahua in central Mexico.

Mixtec – Shared Indigenous American ancestors with people identifying as Mixtec (Mixteco), primarily in Puebla and La Mixteca—a cultural region in western Oaxaca, Mexico.

Otomí – Shared Indigenous American ancestors with people identifying as Otomí, primarily in Querétaro, Guanajuato, and the State of Mexico.