In a new study published today in Nature Communications, 23andMe researchers identified 15 genetic variants associated with being a morning person, including four never-before-connected to sleep cycles and associations like BMI and depression.

Circadian Rhythm Genes

“Some circadian rhythm genes we identified have been studied in model organisms, but much less so in humans,” said David Hinds, Ph. D., a Principal Scientist and Statistical Geneticist at 23andMe, who was a co-author on the paper. We also identified new genes that have not previously been associated with sleep behavior.”

Among the genetic variants in this study, researchers found seven in or near genes already known to play a biological role in circadian rhythms. Four other variants identified are in or near genes that could plausibly be related to circadian rhythm, and the remaining four variants are more of a mystery in their role in human sleep cycles.

Related Phenotypes

Analyzing the phenotypic data, the researchers also examined associations between morning habits and conditions such as body mass index, insomnia, depression, and sleep duration.

They found that a morning person is much less likely to have insomnia, less likely to require eight hours of sleep, and less likely to suffer from depression than individuals who reported being “night owls.” Considering the effect of age and sex, morning persons are also more likely to have lower BMI, according to the research. The researchers also found that morning persons were less likely to be on the extreme ends of body mass index, meaning they were less likely to be obese and less likely to be underweight.

While this does not imply causation, some associations may warrant a deeper dive into biology. For instance, several new genetic associations were found in the FTO gene, which is associated with obesity.

Night Owl or Morning Person

Circadian rhythms are sleep and wake cycles in a 24-hour day. The cycle is triggered by changes in light stimulation. While scientists have long known that one’s genetics can influence one’s circadian rhythm, they have yet to piece together the full picture.

However, understanding why someone is more likely to be a morning person or a “night owl” continues to perplex researchers. By learning more, researchers may better understand certain health conditions associated with those differences, such as depression, obesity, and insomnia.

23andMe’s genome-wide association study examined data from more than 89,000 customers who consented to research and answered questions about their sleep cycles. Using imputation—statistical methods to infer unobserved genotypes—the researchers were able to examine approximately eight million genetic variants, giving them a much more robust picture of the genetic influence on sleep cycles.

Morningness

On the eve of 23andMe’s paper’s publication, a team at the University of Exeter Medical School in the UK completed a similar study.

The researchers there used data from 119,000 individuals in the UK Biobank study and coordinating with 23andMe’s researchers, they were able to replicate 13 of the 16 variants they found associated with being a morning person or “morningness” in that data, including finding variants in genes associated with BMI and circadian rhythms. A preprint of the team’s paper, which is in review for publication, is posted here.

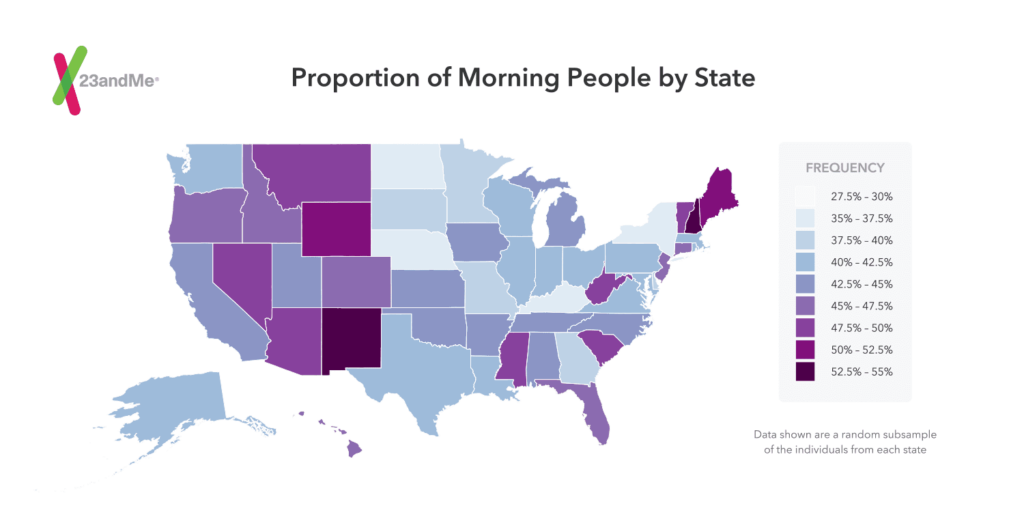

Although not part of the research in this paper, 23andMe scientists looked at this data in another way, precisely how “morningness” distributes itself geographically in the United States. Using random sub-sampling, our scientists looked at the proportion of morning people by state among customers in the US who consented to research.

The map below shows clustering along time zones – especially among the states in the mountain time zone – Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming, and Montana.

According to 23andMe scientist Kasia Bryc, who did the analysis, some of the states with the highest proportion of morning people also tend to have older populations. However, there are many anomalies, making it difficult to draw conclusions. At the same time, the map illustrates that, as with most traits, it’s not just genetics that plays a role.

What do you think explains this distribution?

The paper appears in the journal PLoS Genetics.