People chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus currently have only one treatment option. The treatment combines polyethylene glycol (PEG)-related interferon-alpha and ribavirin (RBV).

This drug regimen fails to eradicate the virus in about half of all patients who receive it, but even when it does work. Not only that, but the side effects can be so harmful that treatment has to be scaled back or abandoned altogether.

New Research

In up to two-thirds of all hepatitis C patients, RBV treatment leads to the destruction of red blood cells. In addition, it decreases the amount of oxygen that can be transported throughout the body, a condition called hemolytic anemia.

New research, published online yesterday in the journal Nature, shows that genetic variants that cause a usually benign enzyme deficiency actually offer some protection against this condition.

The study was conducted by researchers Jacques Fellay, Alexander Thompson, and Dongliang Ge at Duke, along with colleagues from the Schering-Plough Research Institute and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Together, they studied about 1300 European Americans, 200 African Americans, and 100 Hispanics receiving hepatitis C treatment.

The patients had their hemoglobin (the oxygen-carrying protein in red blood cells) levels measured at the beginning of their treatment. Then, measured again at the four-week mark. This is when many patients must begin treatment to stimulate red blood cell production due to RBV-induced anemia.

The researchers also analyzed the patient’s DNA. They looked for genetic variants associated with hemoglobin level changes.

Genetic Variants of Interest

The researchers found several variants on chromosome 20 had a significant association with maintaining good hemoglobin levels after RBV treatment. A deeper analysis of this DNA region revealed that the effect could be traced to two variations in the ITPA gene.

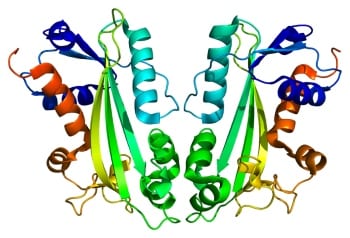

The ITPA gene encodes an enzyme that helps break down a substance called inosine triphosphate in cells.

The less common versions of the two variants the researchers identified reduce the ITPA enzyme’s function.

In most people this isn’t a problem. For people taking drugs called thiopurines, which are used to prevent organ rejection in transplant patients and to treat leukemias and autoimmune disease, reduced ITPA activity may lead to toxicity. What the new study found is that for people receiving treatment for hepatitis C, less ITPA enzyme function is actually a good thing.

Of the people in the current study predicted to have less than one-third of the normal ITPA activity due to their genetics, none ended up with hemoglobin levels below the level traditionally set as a threshold for RBV dose reduction. Of those with normal ITPA levels, 11.7% had their hemoglobin levels dip into the danger zone.

Looking Ahead

More research into the genetics of RBV-induced anemia will be needed. The exact effect varied among the different populations studied, the researchers estimate that about 20-30% of the variability in hemoglobin level reduction in response to RBV treatment was explained two variants. There was no significant association between these SNPs and the efficacy of hepatitis C treatment.

Because having low levels of ITPA enzyme activity do not seem to cause problems for most people.

The authors suggest that drugs that inhibit this enzyme could be developed so that people receiving RBV treatment for hepatitis C could be protected against anemia. Even if they do not carry the protective genetic variations.

Illustration of ITPA protein structure: Emw