In the 1950s, a child born with cystic fibrosis didn’t have much chance of making it to elementary school. But now, thanks to a better understanding of the disease and improved treatments, people with cystic fibrosis live well into adulthood.

A person must inherit a mutated copy of the CFTR gene from each parent in order to develop cystic fibrosis. Hundreds of disease-causing mutations have been documented, and the different mutations and combinations of mutations are known to lead to varying constellations of symptoms and degrees of disease severity. But even in patients with the same combination of mutations there can be differences in how the disease manifests, suggesting that factors beyond CFTR — either environmental or genetic — are involved.

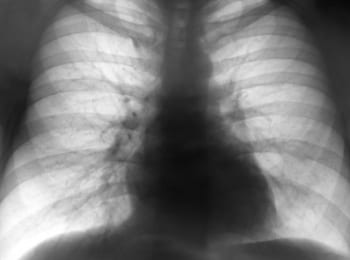

The results of a new study, published online today by the journal Nature, identify a gene that appears to modulate the severity of obstructive lung disease, the major cause of morbidity and mortality in cystic fibrosis patients. And paradoxically, although cystic fibrosis lung disease is largely the result of inflammation brought on by repeated bouts of infection, a variation that leads to reduced levels of lung disease seems to make certain immune cells known as neutrophils less effective at fighting infections.

“Neutrophils appear to be particularly bad actors in cystic fibrosis. They are important to the immune system’s response to bacterial infection. In cystic fibrosis, however, neutrophilic airway inflammation is dysregulated, eventually destroying the lung,” said the study’s senior author, Dr. Christopher Karp, director of Molecular Immunology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, in a statement.

The researchers tested the DNA of more than 3,000 people with cystic fibrosis and found that the IFRD1 gene was associated with lung disease severity. Specifically, people having the CT genotype at rs7817 showed worse lung function than people with either two Cs or two Ts at this SNP.

That would suggest a lung function advantage for CF patients with one copy of each version of rs7817. But in laboratory experiments with cells taken from healthy volunteers, a different and more plausible pattern emerged: Each C at rs7817 led to reduced neutrophil activity. This reduced activity may be the link between IFRD1 and lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis patients.

Research in mice supports that view. Mice genetically engineered to lack the IFRD1 gene show less neutrophil activity, further supporting the importance of this gene in controlling the activity of these cells. When infected with P. aeruginosa, a type of bacteria that often infects the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis, IFRD1-deficient mice were less able to rid their lungs of the bacteria than normal mice. But, as would be predicted from the results in humans, these mutant mice showed fewer signs of inflammation and were actually healthier than the normal mice.

The researchers reason that variations in IFRD1 that reduce neutrophil activity prevent excess inflammation, and therefore reduce the severity of lung disease. The scientists did not address why patients with two Ts had better, not worse, lung function compared to those with one.

Although they caution that more research will be needed, the authors of the study conclude that, “the current data suggest probable benefit for therapeutic targeting of neutrophils in this devastating disease. These data also suggest that [IFRD1] may provide a tractable therapeutic target in CF, and other diseases in which neutrophils have an important pathogenetic role.”

(23andMe customers can find out about their data for one of the most common CFTR mutations, Delta F508, in the Carrier Status Clinical Report for cystic fibrosis. It is important to note that not carrying this mutation does not mean that another mutation is not present.)