Researchers have identified several genetic variations associated with the timing of a baby’s first tooth and the number of teeth at age one. The results, published recently in the journal PLoS Genetics, could be important for understanding more about human health than just this rite of passage all babies must go through.

Nascent teeth form in the womb, but for most babies the first one doesn’t poke through the gums until sometime between four and seven months of age. Some little ones, however, begin teething as early as three months, while others may take a year or more to sprout their first pearly whites. Although the genetic bases for many syndromes involving serious problems with tooth formation have been discovered, until now not much work has been done to understand how our DNA impacts the normal variation in teething seen in the population.

British and Finnish researchers analyzed the DNA of about 6,000 people (approximately 1,500 from the U.K. and 4,500 from Finland) who had been followed by epidemiologists since early in their mothers’ pregnancies. Genetic variants in 10 different regions of the genome had at least a suggestive link to age at first tooth eruption and/or number of teeth at one year. Those SNPs with statistically significant associations with at least one of the traits are shown in the table below.

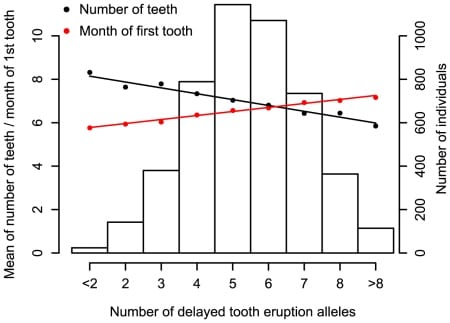

Subjects are classified by the number of delayed tooth eruption alleles. SNPs are chosen so that they had the strongest signal for number of teeth at each locus. Mean time of first tooth eruption is plotted in red and number of teeth by the age of one year in black. The bars represent the number of individuals for each count of ‘delayed tooth eruption’ alleles. The line through points is a linear regression fit. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000856.g002

Subjects are classified by the number of delayed tooth eruption alleles. SNPs are chosen so that they had the strongest signal for number of teeth at each locus. Mean time of first tooth eruption is plotted in red and number of teeth by the age of one year in black. The bars represent the number of individuals for each count of ‘delayed tooth eruption’ alleles. The line through points is a linear regression fit. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000856.g002

Much as has been the case for genetic associations with height, another highly heritable and complex human trait, the variations the researchers linked with teething characteristics explain only a tiny fraction–about 3-4%–of the total variance seen in the population. More studies, with larger samples, will be needed in order to identify more SNPs, including those with smaller effect sizes and rare variants.

Based on the significant SNPs found in the study, the authors defined a summary statistic called the “delayed tooth eruption measure,” which is calculated by adding up how many copies of the “delayed” version of each SNP a person carries. For women the total possible is 10 (two copies of each of five SNPs). Because one of the SNPs is on the X chromosome, for men the total possible is nine.

Based on the Finnish sample, the researchers calculated that individuals with a delayed tooth eruption measure of eight or more have an average of 1.5 fewer teeth at 12 months of age, and later tooth eruption by 1.1 months, compared to individuals with a score of three or less.

The researchers also evaluated whether or not any of the SNPs found in their study of infant teething were associated with the need for orthodontic treatment by age 31 in their Finnish sample. The only significant finding was a SNP that showed only suggestive evidence for an association with timing of first tooth eruption and number of teeth at age one (i.e., it is not in the table above). Each G at increased the odds of requiring orthodontic treatment by 1.35 times.

All of the SNPs identified in this study are in or around genes known to have roles in organ formation, growth and development, or cancer. The authors suggest that studies of teething and other aspects of infant development may have far reaching implications.

“The discoveries of genetic and environmental determinants of human development will help us to understand the development of many disorders which appear later in life. We hope also that these discoveries will increase knowledge about why fetal growth seems to be such an important factor in the development of many chronic diseases, ” said Professor Marjo-Riitta Jarvelin, the study’s senior author, in a press release.