Every family has its stories. We just don’t know them all. That’s where genealogy comes in. Through census and military records, notes in family bibles, or conversations with older relatives we can recover some of those family histories. But where memories and traditional paper records fail, we now have a new genealogical tool — our own DNA. The stories in PBS’ series “Finding Your Roots” illustrate the power of genetic genealogy and the use of DNA to solve family mysteries and uncover hidden stories.

23andMe’s Senior Director of Research, Joanna Mountain, is a geneticist who worked as a consultant on the series and was interviewed for a few of the episodes. Mountain, who completed her Ph.D. in Genetics at Stanford University, is also a guest blogger for the series. Her post below first appeared on the Finding Your Roots program page. We’re republishing it here with the permission of PBS.

I’m a scientist. Mysteries and puzzles have always captivated me. For years I studied the fascinating riddle of human genetic diversity, working both at Stanford University and at the University of California, Berkeley to reconstruct human prehistory using DNA.

I knew the power of DNA to help us understand some of the most fundamental questions of human evolution, but it wasn’t until I applied the same science to my own family’s DNA that I saw how powerful it could be personally.

My own genealogical research started with a brownish-yellow, folded sheet of paper that was handed down to my father from his father. That piece of paper traced the history of the Mountain family back to 1755, just before a 5th great grandfather of mine changed his name from Mounton to Mountain. I was fascinated by how many children my ancestors had, and by how they kept reusing the same first names through the generations. I wondered who had made the effort to record, in such neat handwriting, all the names, birthdays, birthplaces and marriages. This faded piece of paper lent such importance to our family’s surname. We are The Mountains!

At the same time, as a professor of anthropological genetics at Stanford University, I was studying the ancestral lineages of people all over the world through DNA. I spent over 15 years studying the DNA of people in Tanzania, Sri Lanka, Italy, and many other far away places. My own use of genetic genealogy had to wait. It was only in 2007, when I began working for the personal genomics company, 23andMe, that I was able to turn my fascination with genetic variation to my own family. Now 15 of my family members and about two dozen of my husband’s family members have been tested.

One of the first questions I tackled was the genetic lineage of the Mountain line. The challenge was that being female I don’t have a Y chromosome, which is essential for tracing the direct paternal line (from father, to father’s father, to father’s father’s father, and so on). The Y chromosome is one of the two sex chromosomes, the other being the X. Boys inherit a Y chromosome from their father and an X from their mother, while girls inherit an X chromosome from each parent. My father had passed away almost 20 years earlier, and I never had brothers. I knew of just one person with the same Y chromosome as my father — his brother, my uncle Peter in New Zealand. After hearing my pitch my uncle agreed to have his DNA tested. Just a few weeks later the results were in. I learned that my paternal lineage has the name of R1b1b2a1a1d*. Not so meaningful in itself, but this lineage is found mostly on the fringes of the North Sea in England, Germany and the Netherlands, having belonged to residents of Doggerland, a low lying region of forests and wetlands that must have been rich in game… between 9000 and 12,000 years ago. So that’s where the Mountain line originated!

There is no yellowed piece of paper with beautiful handwriting handed down in my mother’s family. In fact, five years ago I knew little more than my maternal grandparents’ names. So I began asking my mother and aunt a few questions. And I checked my results. There is one type of DNA, mitochondrial DNA that all people have, but that is passed down only from mother to child. DNA in the sections of our cells called mitochondria enables us to trace our direct maternal line (from mother, to mother’s mother, to mother’s mother’s mother, and so on) just like the Y chromosome allows people to trace the paternal line. My maternal DNA lineage is called H10a1. This lineage marks a special connection among the group that includes my mother, my sisters and our children. My boys won’t pass on this lineage, but hopefully my niece will have a daughter one day!

The “H” refers to a maternal lineage that originated in the Near East and then expanded, following the decline of the last Ice Age, into Europe, where it is the most prevalent lineage today. Even Marie Antoinette had this lineage! But there are no published details regarding the sub lineage called H10, shared by far fewer individuals than H. To learn more I turned to other colleagues with the H10 lineage. Some, like me, said they trace their ancestry to the United Kingdom. But many more trace ancestry to eastern Europe — Ukraine and Russia. So could my mother’s ancestry trace back to eastern Europe? This was a possibility I had never before fathomed!

Learning my own family’s ancestry connected me to the broader expanse of human history. My DNA not only confirmed what I knew about my English, Irish and Scottish roots, but also revealed deeper roots than I ever imagined along the rim of the North Sea, and a possible newfound link to eastern Europe. As someone, like many Americans, who is far removed from my ancestral homelands, the information connected me to those places. Now I had ancestral stories.

But my family extends beyond my parents and me. I have a husband and two sons, and looking at their DNA added detail and nuance to our family’s story. When we first looked at my husband’s results I thought they were wrong. The results just didn’t fit with what we knew. His family traced ancestry to England, Ireland and Switzerland, but his results pointed to something we hadn’t known about, Native American ancestry on his maternal line. The result spurred my husband to dig more deeply into his maternal line, which is typically more challenging than the paternal line because surnames change each generation. Lo and behold, he found records suggesting that his 6th great grandmother was of mixed ancestry. His South Carolina roots trace not just to European settlers, but also to ancestors living in the Americas 10,000 or more years ago.

Personal genetic information allows you to look not just at your ancient ancestors, but also at very recent connections. One of my favorite moments in this exploration of our family’s genetic genealogy came when my husband and I found some time one evening to show our boys their data. My husband has hazel eyes and mine are brown, but both our sons have blue eyes. It turns out that my husband and I each carry one copy of the “blue” version of an eye color gene, and both of us passed on that version to both boys (one chance in 16!).

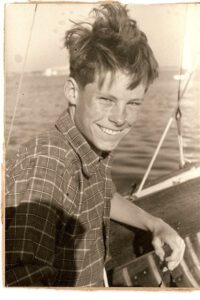

Because my mother had also been tested, we could see that the boys had inherited the blue version from my father, who died almost 23 years ago. So my sons got their blue eyes from my father, the grandfather they never met, who had passed on the genetic variant through me to both of them. When we made this discovery, I quickly looked around for a photo of my dad, finding a tiny one on the office wall. I pointed it out to my younger son, who exclaimed, “Grandpa!” Knowing he had received something in particular from his grandpa strengthened his connection to the man he didn’t know otherwise. And for all of us it added another page to our family’s story.

Joanna Mountain is a geneticist who is a consultant to the PBS series “Finding Your Roots,” and consulted previously on the PBS series “Faces of America.” Dr. Mountain completed her PhD in Genetics at Stanford University and has spent over 20 years studying human genetic diversity. Currently, she is Senior Director of Research at 23andMe, Inc.