It may be you’ve heard a rumor that males are on the brink of extinction.

Whatever you may think of that prospect, the rumor is false. But over the past decade, numerous studies have hinted that the Y chromosome, a male necessity, is going the way of the dodo.

Though other studies have suggested this idea may be a bit of an exaggeration, a new report this week suggests that the Y chromosome may indeed be endangered.

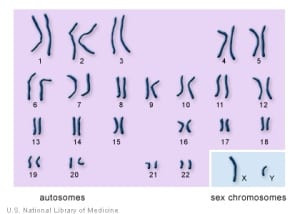

In most mammals, such as us humans, two chromosomes determine the sex of each individual organism: the X and the Y. If an individual’s cells contain two copies of the X chromosome, then they will be genetically female. If they contain one copy of the X and another of the Y, they will be male.

Yet even though these aptly named sex chromosomes have a similar duty – to confer sex – the X and the Y could not be more different. The most striking difference between the two is their size; the Y is less than half as big as the X, and contains only 78 genes, compared to the more than 2,000 found along the X chromosome. The evolutionary history of the two sex chromosomes and the question as to why they are so different from each other has been the subject of heated debate for many years. Now scientists at Pennsylvania State University believe they’ve found a way to uncover not only the difference between the X and Y, but how and why it arose and what this means for the future of the small, but essential, Y chromosome. Their results are reported in the July 17 issue of PLOS Genetics.

The research team, led by biologists Kateryna Makova and Melissa Wilson, believes the key to understanding the origins and future of the Y chromosome lie in some of our most distant mammalian relatives. There are three classes of mammals: egg-layers like the platypus, marsupials like the kangaroo, and the eutherians, which includes humans and thousands of other similar species. While there are many differences between the three groups, one of the most striking is the difference in the organization of the sex chromosomes. As Makova explained, “In eutherian mammals, the sex chromosomes contain an additional region of DNA whereas, in the marsupials and egg layers, this additional region of DNA [is not on a distinct chromosome, but] is [a region of] the non-sex chromosomes.”

The authors argue that the key to the origins of the X and the Y chromosomes may lie in this fundamental difference. By analyzing the X and Y of humans compared to the sex-determining regions of marsupials and egg-laying mammals, Makova and Wilson found that the X and Y split from the other chromosomes about 80 to 130 million years ago.

But that is not all they found. The authors also examined how fast the X and Y mutated over time, and noticed a startling change that occurred at about the same time as the split. “Our research revealed that the Y-specific DNA began to evolve rapidly at the same time that the DNA region split into two entities, while the X-specific DNA maintained the same evolutionary rate as it had previously,” Makova explained.

In other words, as soon as the X and the Y split their own distinct chromosomes, the Y began to evolve much more quickly than its counterpart, mutating at a much higher rate with each new generation. The faster the Y evolved, the faster its genes disappeared. Whereas at one point the Y may have contained thousands of genes, that number has dwindled to the mere 78.

The disappearance of these genes over time and the small number of those remaining on the Y begs the question: will the Y chromosome ever disappear entirely? The authors believed this was an important question to answer as well, and began additional analysis to determine the fate of the Y.

Makova and Wilson reasoned that there must be some utility to the Y, or else it surely would have disappeared by now. As Wilson states, “we know that a few of the genes on the Y chromosome are important, such as the ones involved in the formation of sperm … . Although there is evidence that the Y chromosome is still degrading, some of the surviving genes on the Y chromosome may be essential.” By performing additional tests, they found that there were indeed some genes on the Y that will probably never disappear entirely. But they also found several genes that were already disappearing, and were likely to be gone many generations from now.

Some recent studies have produced evidence that the genes on the Y may not be disappearing as fast as was initially thought. But, according to Makova, the Y chromosome may not be out of the woods just yet. “We still think there is a chance that the Y chromosome eventually could disappear,” she says. “[But] if this happens, it won’t be the end of males.” Instead, she believes that a new pair of sex chromosomes will arise from the genome, latching on to those few remaining genes, keeping alive the genes necessary for male survival.