DNA extracted from bones at a burial site in a rocky valley on a remote island in the South Atlantic could hold important information for those with ancestral roots in Africa.

A fascinating article in Nature, describes work led by Hannes Schroeder to make that connection. Schroeder, a researcher at the University of Copenhagen, and his team have extracted genetic material from skeletal remains of some of the thousands of slaves who were freed by the British Navy between 1840 and 1865.

Taken from slave ships on their way to the New World as many as 20,000 people, many of them children, were saved from enslavement in the Americas, but were then unceremoniously deposited on the island of St. Helena. Sick and emaciated from their brutal ordeal many of them died there. The island’s Rupert Valley is the final resting place of more than 8,000 people.

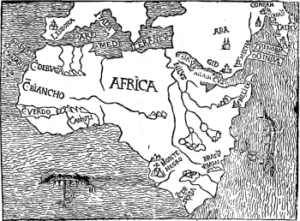

This little known history would have been forgotten altogether if the graves were not found a few years ago during a construction project. The find, and the promise of sequencing the DNA of some of the bones there, offered Schroeder and his team a tantalizing opportunity – a chance to sequence individuals who’d been destined for slavery in the New World but never got there. Their DNA could reveal what written records have failed to track, the specific regions in Africa from where slaves came.

This is the part of Schroeder’s work that is most interesting for us here at 23andMe, where our own African Genetics Project is also trying to make that connection, albeit in a different way.

While much has been done to document the history of the enslavement of the more than 12 million Africans who survived the brutal Middle Passage to wind up in bondage in the New World, this effort, and 23andMe’s, offers a chance to look beyond the limitations of the written record. We know that the Africans enslaved in the Americas were not a monolithic group but individuals from different cultures and with different languages who were forced together into slavery.

Schroeder and his team have already sequenced partial genomes of about 20 individuals, and found that they represent a diverse collection of African groups. As the article notes some of the samples indicate shared ancestry with West and Central African ethnic groups, such as the Bamoun and Kongo. But for the others, matches could not be found. This is likely because there are not diverse reference data sets to compare them too. Schroeder is hoping that two medically-related sequencing efforts in Africa will help change that.

In the meantime 23andMe’s African Ancestry Project has begun to recruit people in the United States, who emigrated, or whose parents emigrated, from several specific countries in Sub-Saharan Africa to improve its set of African reference data. This will not just improve the information we can report back to people of African descent, it could also help yield new insights into the TransAtlantic slave trade.

“23andMe researchers hope to identify direct connections between locations in Africa and the Americas, possibly adding important details to the historical record,” said Joanna Mountain, Ph.D., senior director of research at 23andMe.

Like 23andMe Schroeder and his team are looking to make direct connections from specific locations in Africa and the individuals who wound up in St. Helena. In turn this may also help people of African descent living in the Americas a bridge to their own ancestral past.

Fatimah Jackson, a biological anthropologist at Howard University in Washington DC who is sequencing ancient DNA from other slave burial sites, is quoted in the Nature article as saying that his kind of research has the potential of changing people’s perception of the past.

“It’s a very personal thing for us,” Jackson said. “It’s not just ancient DNA. It’s ancient DNA of potential ancestors.”