Unlike the flu virus, which the body is generally able to fight off completely, infection with hepatitis C is often chronic. That means for most of the three to four million people worldwide who are newly infected each year the virus will persist in the body, where it greatly increases risk for chronic liver diseases including cirrhosis and cancer. The only treatment currently available – an almost year long course of drugs – often causes severe side-effects. Worse yet, it fails in about half of all patients.

Last month, a study published online in the journal Nature showed that DNA variations in and around the IL28B gene influence whether a person chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus will fully respond to the standard treatment regimen. Now three new reports further support the importance of IL28B variations in the body’s response to hepatitis C, a finding that has implications for the future of hepatitis treatment and drug development.

An Australian group headed up by Vijayaprakash Suppiah analyzed the DNA of more than 800 people with European ancestry from Australia, the UK, Germany and Italy infected with hepatitis C. They found that having one or two copies of the less-common G version of , a SNP near the IL28B gene, doubled the odds that a person would fail to have a sustained response to treatment.

A group headed up by Yasuhito Tanaka studied 326 Japanese hepatitis C patients and also found that predicts whether or not a person will respond to treatment. In this population, however, the effect was much greater. Carrying a G increased the odds of treatment failure by at least twelve times.

“This SNP has such a strong association with response that, in combination with other parameters, genotyping it and other genetic variants should be a useful part of clinical management,” write Suppiah et al., who along with Tanaka et al. published their results online this week in the journal Nature Genetics.

Another study, this one published online in Nature, found that variation near IL28B might be part of what allows a minority of people infected with hepatitis C to clear the virus naturally, without any treatment.

David Thomas and colleagues found that individuals with European or African ancestry were about three times more likely to spontaneously clear a hepatitis C infection if they carried two copies of the C version of than if they had CT or TT at this SNP.

Twenty-eight percent of the people with the CT or TT genotypes were able to fight off their hepatitis C infection without treatment, a number very close to the population average. But 53% of those with the CC genotype were able to become naturally virus-free.

In a commentary published in Nature, Shawn Iadonato and Michael Katze express doubts about the importance of these new discoveries.

“Although these findings raise the tantalizing prospect of a more personalized approach to treating [hepatitis C] by tailoring treatment to patients who are most likely to benefit, the reality is more sobering,” they write.

Iadonato and Katze worry that testing for IL28B variations would not provide doctors with a straightforward yes-or-no answer to the question of whether a patient will respond to hepatitis C treatment. This is because not all carriers of the advantageous versions of the variants clear the virus, nor do all patients lacking them fail to benefit from treatment. Furthermore, they point out, there is currently no alternative hepatitis C treatment available.

What they do not consider, however, is how this new research may help change that. In a separate commentary in Nature Genetics, Thomas O’Brien suggests that the current findings could increase the interest in developing hepatitis therapies based on the protein encoded by IL28B, interferon-λ3. He notes that an early clinical trial testing the effects of a related protein, interferon-λ1, has already had some success. And certain properties of interferon-λs may cause them to have fewer side effects than current treatments.

O’Brien is still cautious about the findings linking IL28B variations to hepatitis C treatment response. He says that more research in this area is needed in diverse populations and in people infected with different forms of hepatitis C. He also stresses that researchers need to consider how these genetic findings fit in with other factors that affect treatment response, including age and gender.

Overall, however, his view is optimistic. He concludes: “With these caveats, predictive models of HCV treatment response hold the potential to inform treatment decisions for millions of patients who are infected with HCV.”

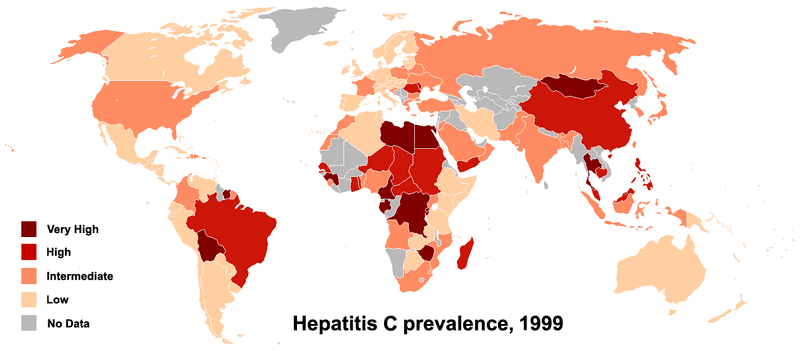

Map: PhilippN