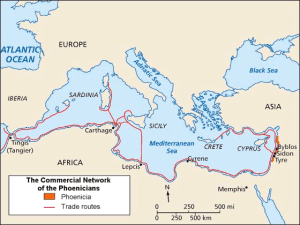

About 3,500 years ago, the Phoenicians expanded from their homeland in present-day Syria and Lebanon, using their superior maritime technology to establish trading posts across southern Europe and North Africa.

The Rise and Fall of the Phoenicians

They traded silver from Iberia, copper from Cyprus, and textiles from Morocco. They built cities in Sicily, Malta, and Tunisia that rivaled those in Greece and Rome. However, by the 1st century BC, nearly all evidence of their power and authority over Mediterranean trade routes had vanished.

The Phoenicians’ fate as a maritime power is well documented. The Persians conquered the Phoenician homeland in 539 BC. Two centuries later, Alexander the Great’s army swept in from the west. Finally, the Roman Empire conquered—and destroyed—the Phoenician city of Carthage in 146 BC following the Third Punic War.

The Disappearance of the Phoenicians

But what happened to the Phoenicians themselves? Were they wiped out, too? Or are their descendants still alive today?

In a study published this week, researchers identify Phoenician-specific DNA markers in present-day Mediterranean populations, demonstrating that genetic traces of the ancient civilization still exist in some modern-day peoples. These people could be descendants of the Phoenicians themselves.

It has always been difficult to use genetics to trace specific historical migrations, such as the Jewish Diaspora, the Norman invasion of Britain, or even the Viking expansions into Western Europe.

Using DNA to Tell a Story

Attempting to trace migrations across the Mediterranean is even more arduous, as there have been multiple migrations at different times throughout history. How do scientists sort out each unique migration event over the long and complex population history of the region? A team of geneticists from National Geographic and IBM’s Genographic Project believes they have found a way to do just that. They discuss their research in the latest American Journal of Human Genetics issue.

Traditionally, when scientists want to understand the genetic history of an area, they collect DNA samples from the entire region of interest. But in this case, the authors of the AJHG paper collected samples from specific towns and cities that are believed to have been built on or near ancient Phoenician archaeological sites, including Carthage, Cyprus, and Sicily. They reasoned that if descendants of the Phoenicians do indeed exist, they would more likely be found near these sites.

Tracing Paternal Lines

Armed with this newly collected data, the authors focused on the Y-chromosome to trace the Phoenicians’ genetic history. According to Chris Tyler-Smith, one of the study’s authors, “We chose the Y-chromosome because its male-specificity means that it would have been carried by the predominantly male Phoenician traders.” They then used a newly devised analytical method of distinguishing any Phoenician migration from other geographically similar migrations. Their results are surprisingly informative.

The authors found a weak — but significant — genetic signature among their samples that could not be explained by chance. Many of the samples belonged to a particular branch of haplogroup J2, which the authors believe points back to distinct migrations by Phoenician traders from the Middle East into Europe and North Africa more than 3,000 years ago.

The applications of the authors’ new approach to studies of population history are incredibly far-reaching. Perhaps similar analyses could be used to trace the genetic footprints of Alexander the Great and his army into Persia during the 4th century BC or migrations along the Silk Road from China during the Middle Ages. The authors even propose that their technique could be used within populations to discover historical migrations that we never even knew existed.

Photograph courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.