First came the Human Genome Project when, in the year 2000, an international team of scientists began mapping all 23 pairs of our chromosomes. Then in 2005, the Chimpanzee Genome Project took off, attempting to do the same for the 24 chromosomes of our species’ closest living relative. With intimate knowledge of the genetic make-up of both species, scientists could decipher the evolutionary changes that took place in the 7 million years since the time of our last shared ancestor.

Now, a joint research team led by Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology has gone one step further by mapping the complete genome of our nearest extinct relative. Pääbo and his colleagues announced the completion of a draft Neanderthal genome sequence today in Chicago at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

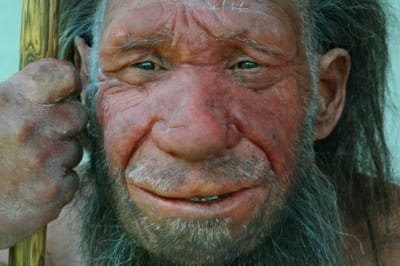

Neanderthals – our short, stocky, evolutionary cousins – lived in Europe during the harshest conditions of the Ice Age. They survived in regions where few other animals could. Neanderthals first came on the scene over 350,000 years ago, but seemed to dwindle in numbers with the arrival of humans about 40,000 years ago. By 25,000 years ago they had disappeared completely.

But there are still many questions surrounding the fate of the Neanderthals. While most scientists argue that Neanderthals were simply out-competed by the arriving humans, some believe that Neanderthals and early humans may have interbred, and that many modern Europeans have Neanderthal DNA interspersed throughout their genome. Others believe that Neanderthals and early humans were in fact members of the same species, and should therefore have very similar DNA.

Solving the mystery has been no easy task. Because the archaeological samples available to Pääbo and his colleagues – three bone fragments from a cave in Croatia – are 30,000 years old, what little DNA they contain has been broken down into short fragments of just a few hundred base pairs each – a fraction of the billions that make up a complete genome.

Initially, the researchers focused on the mitochondrial DNA, because it is so prevalent in each cell. When comparing the mitochondrial DNA of Neanderthals to that of modern humans, they found substantial differences between the two – indicating that humans and Neanderthals could not have been members of the same species.

However, the mitochondrial DNA represents only a fraction of the entire Neanderthal genome. If we want to know the real genetic differences between humans and Neanderthals, then we’ll have to examine not just a small fraction, but the whole genome – all 46 chromosomes of it.

Working with 454 Life Sciences Corp of Branford, Conn., Pääbo and his team have devised a way to extract large amounts of nuclear DNA – DNA from the 23 pairs of chromosomes inside each cell – from prehistoric mammals, including Neanderthals. All told, the two research teams have so far sequenced over 3 billion bases of Neanderthal nuclear DNA, constructing a ‘rough draft’ of the entire Neanderthal genome.

The sheer difficulty in completing such a task cannot be underestimated. As soon as these Neanderthals died, tens of thousands of years ago, the DNA inside each cell began breaking down. Up until recently, extracting the few remaining bits of DNA from fossils like these was virtually impossible. Now, as Pääbo and others comb through the Neanderthal genome, we can embark on new chapter in the continuing saga surrounding the relationship between humans and Neanderthals.