by Samantha Ancona Esselmann, Ph.D., product scientist at 23andMe

When 23andMe scientists added a “Filipino” population to our Ancestry Composition report two years ago, customers were excited to see their Filipino ancestry reflected in their results for the first time.

Only, there was a twist! Many customers with no known Filipino ancestors were getting 5 percent, 20 percent, even 50 percent or more of this ancestry, and were understandably confused.

In response to customer feedback, our team performed more analyses and confirmed that we were missing a big part of the story — or maybe a better way of saying it was that we were missing a big part of the human migration story.

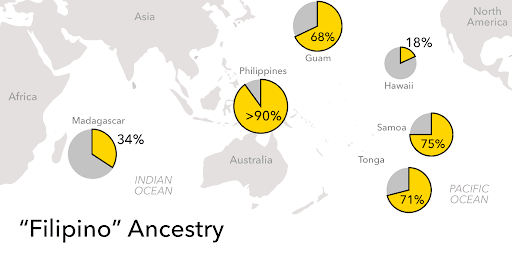

It was true that people with the highest proportion of “Filipino” in their ancestry estimates were actually of Filipino descent (over 90 percent on average), but this so-called “Filipino” ancestry reached an average of 75 percent in customers from Samoa, 71 percent in Tonga, 68 percent in Guam, 18 percent in Hawaii, and even 34 percent among customers from Madagascar, off the southeastern coast of Africa.

Clearly, this update was not just identifying Filipino ancestry, but a shared genetic heritage that was spread across nearly two-thirds of the circumference of the globe.

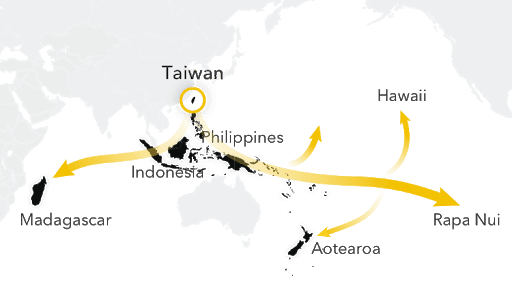

Our ancestry scientists realized right away that this shared ancestry was a reflection of human migration and the major expansion of seafaring people who spoke Austronesian languages that began around 5,000 years ago near Taiwan and spread across a vast part of the world.

We renamed the population to “Filipino & Austronesian,” and the population description was updated to shed light on this shared linguistic, genetic, and cultural history.

Here are our favorite stories about the “Austronesian Expansion,” from out-of-this-world navigation techniques to the gut bacteria that hitched a ride across the sea.

The Final Frontier

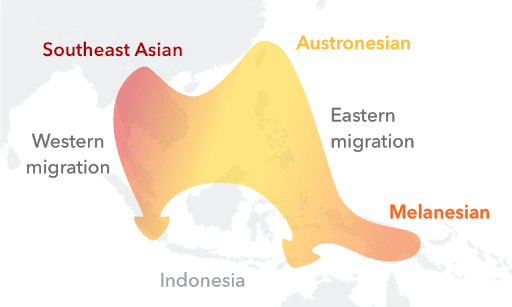

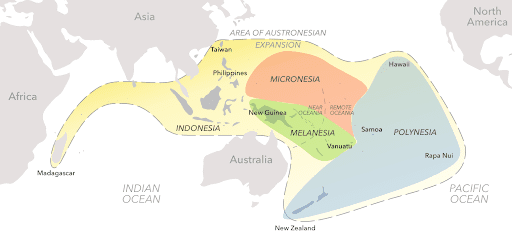

Around 5,000 years ago, Austronesians began a millennia-long expansion into the Pacific from Taiwan. They carried their knowledge of navigation and farming more than halfway around the world. They expanded through the Philippines and Indonesia all the way to Hawaii in the east and Madagascar in the west. During this expansion, the Austronesians mixed with people they met along their way, including the indigenous Filipinos, Papuans (whose ancestors are thought to have arrived over 50,000 years ago), and Southeast Asian mainlanders.

Polynesian culture later emerged from Austronesian societies in Tonga and Samoa. It spread to the equatorial islands of the central Pacific — including French Polynesia — as recently as 1,000 years ago. Soon after, Polynesians settled the far-flung lands of Hawaii, Aotearoa (New Zealand), and Rapa Nui (Easter Island). This late, rapid settlement is thought to explain the remarkable similarities between the cultures and languages of the remote Pacific.

Way-finders

Long before the European Age of Exploration, Polynesian voyagers were crossing thousands of miles of uncharted water, settling one uninhabited island after another. Almost all knowledge of traditional Polynesian navigation is lost to time, but their techniques likely included:

- “Wave-piloting,” which involves sensing the reflections and refractions of ocean swells off of distant islands.

- Following birds or turtles to land.

- Spotting island-hugging bioluminescence.

- Relying on memorized star maps as a guide — a skill highlighted in the 2016 animated film, Moana.

Only a handful of Pacific Islanders carry the traditional knowledge of wave piloting, but in 2006, researchers accompanied a Marshallese wave pilot on a journey between islands. To navigate the journey, the wave pilot relied only on his ability to read the ocean swells. In a test of the wave pilot’s skill, the researchers set the ship miles off-course while the navigator slept. But soon after he woke up, the wave pilot had the ship back on course, having correctly interpreted the pattern of waves reflecting off a nearby island.

Language on the move

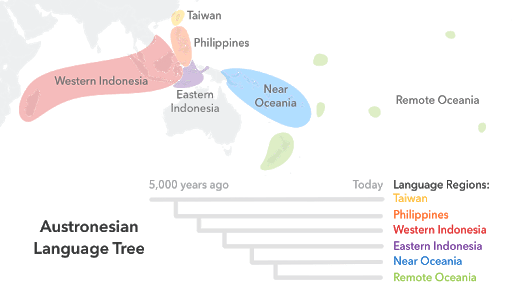

Before DNA shed light on the origins of Austronesians, studies of their languages pointed to an Austronesian origin closely related to the indigenous people of Taiwan. A team of scientists in New Zealand built a database of simple words from 400 Austronesian languages, and by focusing on cognates (similar words that mean the same thing), the team was able to build a family tree of Austronesian languages — with indigenous Taiwanese Formosan languages at the root. Branching from there were the languages spoken in the Philippines, Indonesia, New Guinea, Fiji, and finally, the closely related Polynesian languages, such as Samoan, Maori, Tahitian, and Hawaiian.

This language tree mirrors the genetic relationships of a number of other living things found throughout the Pacific — from gut bacteria to paper mulberry plants (used to make barkcloth). Researchers believe these different organisms originated in Taiwan and hitched a ride across the Pacific with the Austronesian voyagers.

Melanesian Exchange

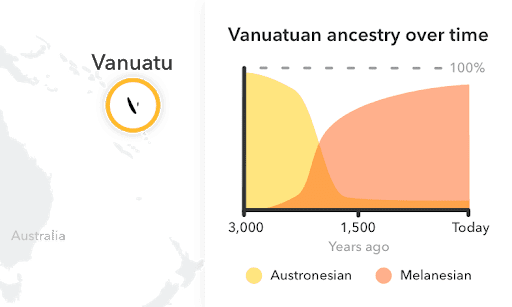

The ancestors of Melanesians — the indigenous inhabitants of Near Oceania — reached the islands of the western Pacific much earlier than the Austronesians. They arrived on these islands well over 50,000 years ago. Today this ancestry is common in populations from Papua New Guinea to Fiji, a distance spanning over 2,500 miles. But, the oldest human remains found on Vanuatu (an archipelago between New Guinea and Fiji) and on islands further East aren’t Melanesian. So when did the Melanesians reach Vanuatu and who was there before them?

A recent study of ancient human remains from Vanuatu showed that Austronesian settlers first reached Vanuatu around 3,000 years ago. Soon after, people with Melanesian ancestry began to arrive. Today, even though Vanuatuans speak primarily Austronesian languages, they have mostly Melanesian ancestry.

It seems that early Melanesian voyagers halted their eastward migration in the Solomon Islands. They only ventured further into the Pacific after a new wave of voyagers — the Austronesians — passed through the region to settle Vanuatu, Tonga, and other remote Pacific islands. Today, almost all populations in the remote Pacific have more than 25 percent Melanesian ancestry. This is despite initial settlement by Austronesians.

Indonesian Melting Pot

Indonesia is genetically diverse. This is not particularly surprising for a 3,000-mile-wide nation made up of more than 17,000 islands.

Austronesian ancestry is found throughout Indonesia. But where the inhabitants of the large western islands have strong genetic ties to the Southeast Asian mainland, the inhabitants of the islands east of Bali have very little.

The most likely scenario is that a western group of Austronesian voyagers mixed with people in southern Vietnam or the Malay Peninsula. This mixed population likely continued on to settle western Indonesia. Eastern Indonesia, on the other hand, is home to people with a combination of primarily Austronesian and Melanesian ancestry.

The Malagasy Mystery

The Malagasy people of Madagascar speak an Austronesian language, but Madagascar is a world away from Southeast Asia. Malagasy people also have African ancestry. So who reached Madagascar first and where did they come from?

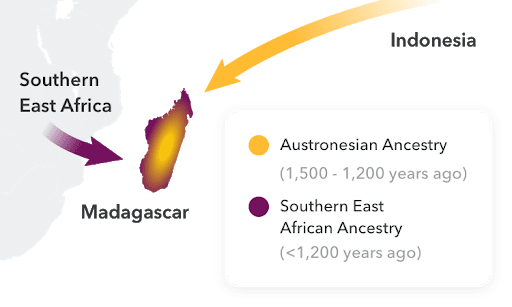

Although the African continent is much closer, there is cultural, genetic, archaeological, and linguistic evidence pointing to an initial settlement of Madagascar by Austronesian voyagers between 1,200 and 1,500 years ago. This was followed by the arrival of Bantu speakers from southern East Africa.

Linguistic and genetic studies showed that the Austronesian founders of Madagascar were most closely related to present-day groups living in central and eastern Indonesia (1, 2, 3). These studies also revealed that African ancestry is generally higher in Madagascar’s coastal lowlands. Austronesian ancestry reaches higher levels in the country’s central highlands.

Customers can see these stories on the Filipino & Austronesian Ancestry Detail Report page. Not yet a customer, find out more about 23andMe’s Ancestry + Traits service here.

Customers can see these stories on the Filipino & Austronesian Ancestry Detail Report page. Not yet a customer, find out more about 23andMe’s Ancestry + Traits service here.