Esteban G. Burchard, MD, MPH

Asthma can start with simple tightness in the chest, but end in an epic battle to breathe.

So whether you are black or white, Asian or Latino, an asthma attack can be frightening, especially if you are a kid.

But who you are, or more accurately what your ancestry is, does matter in what scientists can say about the triggers, causes and biology of the disease.

There has been a lot of research that’s been done on asthma, and we know a lot about the condition. But the vast majority of that research has been done only on people of European ancestry, and in many cases it offers little insights for people of other ethnicities.

Some estimates show that more than 90 percent of the research into the genetics underlying disease is on individuals of European descent alone.

That’s a problem for everybody, according to the University of California at San Francisco Professor Esteban Burchard, an MD, MPH.

“Almost all the genetic studies of asthma have been done using white patients only, but you can’t assume these results will apply to other ethnic groups,” said Esteban, who directs the Genes-environments & Admixture in Latino Americans Study and the Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes & Environments at University of California San Francisco.

He also serves as an expert on research disparities for President Obama’s Precision Medicine Initiative.

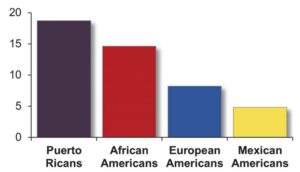

Asthma prevalence among children of different ancestry.

A long-time friend of 23andMe who previously served as an advisor in the company’s effort to recruit more African Americans called “Roots into the Future,” Esteban said that the lack of diversity in research leaves non-Europeans behind in the genetics revolution and it leaves huge gaps in scientists’ understanding of disease.

There are efforts to change that.

Recently 23andMe received a National Institutes of Health grant for a project that uses admixture mapping as a way to aid gaining better insight into health research for underrepresented communities. While this doesn’t involve recruiting, it could help leverage 23andMe’s diverse collection of customers who have consented to research.

The need for these kinds of approaches to improve diversity in research are very apparent. Asthma is a case in point. It is the most common chronic disease among all children, but it hits African American and Puerto Rican kids at almost twice the rate of all other children. About 18 percent of Puerto Rican children have asthma, while about 15 percent of African American kids do.

Addressing this head on, Esteban recently lead a team that completed the largest single study of the genetic and environmental causes of asthma in African American children. The study suggests that only a tiny fraction of known genetic risk factors for the disease that have been discovered in other research actually apply to African Americans.

“This paper is an important first step towards truly understanding the biology of asthma in African Americans,” Esteban said.

The paper also reinforces the importance of gathering more research data on people of all ancestries to improve the insights that can be gained through genetic research.

The study included data from more than 1,200 African Americans, about 800 of whom have asthma, to look for genetic variants associated with the disease. The researchers looked at genetic variants known to be associated with asthma in people of European ancestry. They found that 95 percent of the variants that increase risk for asthma in Europeans didn’t appear to increase risk for African Americans. And for the first time they identified genetic variants associated with higher risk for asthma in African American children. Those variants were in or near genes that are also associated with obesity and inflammation, which could help researchers as they investigate the biology of the disease.

For Esteban this clearly shows the value of the research the team is doing by focusing on people of color.

“We want to understand why some minority communities have higher rates of disease and how they may respond differently to treatment,” he said. “But the risk factors we identify in these understudied populations can also point the way to new biology, which can be important for everyone.”