Before a medicine reaches pharmacy shelves, it goes through extensive and rigorous evaluation to prove it is safe and  effective.

effective.

We want to shed some light on a few of the steps involved in drug development and highlight how the work being done by 23andMe with the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Study can help inform this process in the future.

The basics

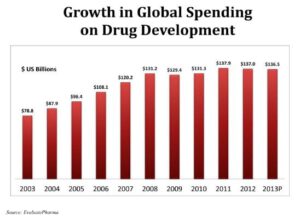

On average, it takes somewhere between 11 and 14 years for a drug to go through development. This extensive process can cost up to $5 billion. Of all the medicines that start the clinical development process, less than 10 percent make it through all the stages of clinical trials and through Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval. The majority of the drug

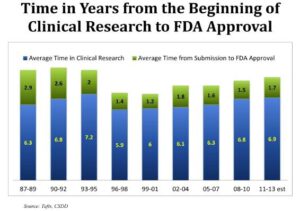

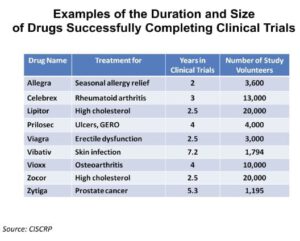

Image: The Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation

development timeline is taken up by conducting the clinical trials (6-11 years), and one of the most time-intensive parts of running clinical trials is finding study volunteers. Only 7 percent of Americans say their doctor has ever suggested they consider participating in a clinical research study.

What happens before clinical trials?

Before a medicine enters clinical development, it goes through years of testing in the laboratory, using cell culture and animals to better understand how the drug works and to ensure it’s safe.

Clinical Trials: Phase I to Phase III

The very first study of a new medicine in people is called a “phase I” study. This type of study is very small – just a handful of volunteers are given the drug, starting at very low amounts. The dose is increased incrementally until they find a dose that is safe and also high enough to be considered active.

Image: The Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation

The next study, a “phase II” trial, is larger and looks for safety as well as efficacy. Essentially this phase looks at whether the drug does what it is meant to do. Does it improve the symptoms or alleviate the disease?

A “phase III” study is the largest still and often includes a “control” group – volunteers who are given the standard-of-care medications (not the experimental drug) for comparison. The FDA then reviews the data collected from these trials. The FDA can then request additional studies, or it can “clear” the drug for use (meaning the manufacturer can go ahead and sell the drug.)

How can genetics impact the drug development process?

Newly approved medicines provide benefits to many people. They alleviate symptoms, or sometimes cure a disease. However, they don’t work well for everyone. Many people take medicines which don’t help their condition, or sometimes lead to unacceptable side effects. There is no way to know which medicines will work for which patients. The method of finding the right treatment for any patient is still very much a “trial and error” process – the doctor keeps prescribing different medicines until he or she finds one that works.

This is where genetics may play a role in improving the process. We know that genetics can influence how people respond to drugs. By studying the genetics underlying diseases, such as Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), we hope to provide more insights into how IBD differs between people. It is possible that there are certain genetic variants which can predict what type of drug would be most effective, or cause the least side effects.

A better understanding of the genetics of IBD can change how clinical trials are done, which can in turn bring medicines to the market faster and provide guidance to physicians about which patients will most benefit from which drugs.

Image: The Center for Information and Study on Clinical Research Participation

Patients who enroll in clinical trials of new medicines must meet several specific eligibility criteria. For IBD, right now those criteria may involve a list of medications the person must have taken (and failed) and/or a specific range of acceptable lab results.

In the future, the eligibility criteria for an IBD trial may include lists of specific genetic variants that participants need to have in order to enroll in the study along with other precise measures of disease such as the composition of their microbiome (the types of bacteria in their gut). In this way, only those patients who would most benefit from the experimental medicine would be enrolled, sparing patients with no hope for efficacy the potential side effects of the drug and allowing them to find other clinical trials better suited for their IBD.

Precision medicine (prescribing the right medication for the right patient at the right time) is already a reality in the treatment of many cancers. Examples of such drugs are: trastuzumab (HerceptinⓇ) for the treatment of HER2 positive breast cancer, cetuximab (ErbituxⓇ) for the treatment of colorectal cancer which carries a mutation in the EGFR gene but not the KRAS gene, or crizotinib (XalkoriⓇ) for the treatment of lung cancers with an ALK gene fusion.

The reality of genetically targeted medicines is still not yet realized for IBD, but we are helping lay the groundwork through our research efforts and collaboration with Pfizer, a manufacturer of new treatments for IBD.

Observational studies (where no drugs or treatments are involved) such as our IBD study play an important role in providing a basic understanding of the disease. We hope the results of this study will directly inform Pfizer’s drug development efforts and help us move just a step closer to the future of precision medicine approaches in IBD.