Scientists at 23andMe, with support from The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, have researched Parkinson’s disease and uncovered new insights into the natural history of the LRRK2 G2019S variant. The findings, tracing back thousands of years, vividly illustrate how our DNA combines history, ancestry, and health. They remind us how important knowing one is for understanding the other.

Your Genetic Ancestry Relates to Health

While some of us use 23andMe to learn more about our health and others to learn about our ancestry, your DNA isn’t just about one thing or the other. Your DNA intricately weaves together not just your health and ancestry but much more, connecting you to the long thread of human history and offering insight into the origin of diseases like Parkinson’s.

The history of the LRRK2 G2019S variant and its geographical distribution in disparate communities are telling.

“The fact that the LRRK2 G2019S variant is found in North African Arabs, Ashkenazi Jews, Sephardic Jews, and populations in Latin America and the Caribbean tells a story of our shared genetic roots,” said Lucy Norcliffe-Kaufmann, Ph.D., Principal Scientist with 23andMe’s Parkinson’s Disease Research program.

The Founder Mutation

Studying specific genes, like LRRK2, can teach us much. The LRRK2 variant—also known as the LRRK2 G2019S founder mutation—is strongly associated with a particular form of Parkinson’s disease, which we’ll briefly detail.

First, let’s explain a founder mutation. A founder mutation refers to genetic variants arising from a population’s loss of genetic variation. This happens when a distinctive population emerges from a small number of people isolated by geography or culture for a considerable time.

The isolation of small populations can result in a higher-than-average frequency for specific genetic variants within that population.

For example, over generations, the geographic isolation of Finnish people led to a founder mutation that puts them at a higher risk for a kidney condition known as congenital nephrotic syndrome. The isolation of French Canadians in Quebec offers another example. That isolation led to a founder mutation in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes that puts them at higher risk for breast and ovarian cancer.

Some of the most well-known founder mutations are among people with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Isolated over time by culture, religion, and, in some cases, geography led to higher incidences of specific genetic variants within Ashkenazi populations. These genetic variants put them at higher genetic risk for breast and ovarian cancer.

But people of Ashkenazi ancestry are also more likely to have the LRRK2 G2019S founder mutation that puts them at more risk for a specific type of Parkinson’s disease.

LRRK2-Associated Parkinson’s

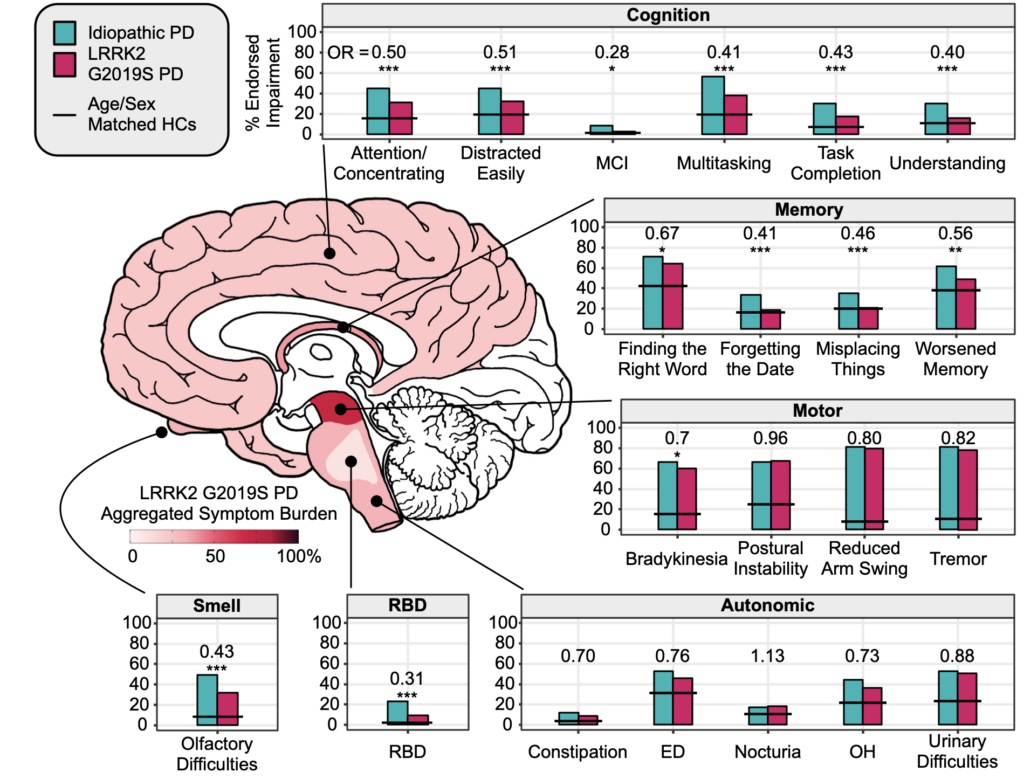

Looking specifically at LRRK2 G2019S, the variant doesn’t just convey an increased risk for Parkinson’s. People who develop the disease who have the variant also have different types of symptoms than others with Parkinson’s but who do not have the LRRK2 variant.

23andMe researchers recently published data in Brain, that looks at some of those differences.

People with LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s disease tend to have a slower progression of the disease, with symptoms more related to motor dysfunction. People with this LRRK2 variant also have lower rates of REM sleep behavior disorder or RBD, which is a common symptom of Parkinson’s, particularly in the early stages. RBD includes sleep interrupted by acting out dreams and is much more common in people with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, or Parkinson’s, in which the cause is unknown.

Different Types of Symptoms

Loss of smell, another common symptom of Parkinson’s, is also less common in those with the LRRK2 variant. This is important because when we look for people with early Parkinson’s disease, we ask about loss of smell and RBD to determine whether there are early signs of neurodegeneration in the brain. We might be underestimating the risk of Parkinson’s disease in someone with the LRRK2 variant because they are less likely to have sleep and smell problems.

In addition, people with LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s have fewer cognitive issues and seem to be at a lower risk for developing dementia. This suggests that the LRRK2 variant leads to a slowly primarily progressive motor form of Parkinson’s disease, in which the neurodegenerative process appears to be restricted to areas of the brain that control movement. The data suggests that in LRRK2 Parkinson’s disease, the areas outside the motor control regions are spared from the neurodegenerative process, so we see fewer autonomic, cognitive, sleep, and smell issues in carriers that develop the disease.

The researchers point out that it’s unusual to see a dominant mutation like LRRK2 so prevalent across different communities, but that may be partly because of the later onset of LRRK2-associated Parkinson’s. Symptoms tend to show when people are in their 60s and well past reproductive years.

“This explains why the variant can be harbored in a community and flourish in subsequent generations, particularly in communities that remain isolated by persecution or geography,” Lucy said.

These differences beg many questions, but they also offer potential avenues of inquiry that could give researchers insights into how to treat different types of Parkinson’s disease better. The majority of Parkinson’s cases do not have a known cause, but in the case of LRRK2, because the association is known, knowing that you have the variant sooner can lead to earlier treatment and better outcomes.

To develop new therapies, scientists need to learn more about who is at risk, why, and the earliest signs of the disease.

The Origins of LRRK2 Variant

Beyond that, tracing where and when the LRRK2 G2019S founder mutation originated offers other opportunities to find carriers in diverse populations and build community among those people.

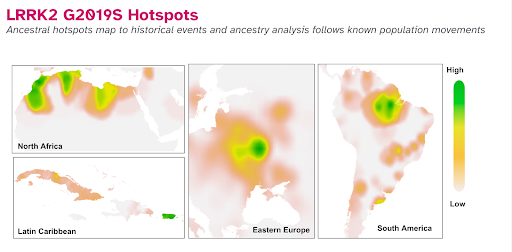

Looking at the history of the LRRK2 founder mutation also offers insight into human migration and some of the people most impacted by it. One of the novel findings of this study is the identification of “hotspots” of people from Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Brazil who carry the LRRK2 G2019S mutation at higher rates. This is interesting because it explains the migratory history of the populations most affected by this mutation.

Scientists believe the LRRK2 founder mutation originated over 5000 years ago among the Berber people of North Africa in what is now Morocco. Rates of LRRK2 are higher within North African populations, but why are there also higher incidences of people with LRRK2 within people of Ashkenazi Ancestry?

Why is LRRK2 also found in higher frequency in North Africa and parts of Spain, Eastern Europe, Cuba, and Puerto Rico? That latter finding for a higher frequency of people in the Latin Caribbean community with higher rates of this variant is a new finding from this research by 23andMe, and it begs the question of why we see those higher rates.

The answer lies in the unique history of people of Jewish ancestry, shaped by trade routes around the Mediterranean and historical events like the Muslim Arab expansion, the Crusades, the Inquisition, and the colonization and migration into the Americas.

Tracing LRRK2

Scientists believe the LRRK2 founder mutation originated in the Berber populations of North Africa and then passed through the Maghrebi into the Jewish communities that arrived there, having fled the Roman invasions of Jerusalem.

The Maghrebi were mostly traders connected to other Jewish communities by religion and trade routes that crisscrossed the Mediterranean. The Berbers and the new Jewish settlers lived side by side, and many Berbers converted to Judaism, which is likely how the LRRK2 G2019S variant moved from the Berbers to the North African Jews.

Some of those communities eventually migrated from North Africa to mainland Europe with the Arab invasions. Around 1,500 years ago, about eight percent of people living in Spain were of Jewish descent. Within a couple of hundred years, the Jewish population split, with the Ashkenazi group settling in Germany, France, and Eastern Europe and speaking Yiddish. Meanwhile, the Iberian-Arab Jews, later known as the Sephardic Jews, moved to and from North Africa to Spain and Portugal over the next hundreds of years.

While different significant historical events, such as Muslim Arab expansion and later the Crusades, influenced the movement of these people, we can already see that the LRRK2 G2019S variant was present in both the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews. The Ashkenazi Jews went through what we call a genetic bottleneck, which reduced the population pool to a small number of founders, some of whom carried the G2019S variant. This is how the carrier rate amplified as the small surviving population recovered and expanded over subsequent generations.

The New World

By the time the Inquisitions arrived, many of what became the Sephardic Jewish community in Spain and Portugal were expelled or forced to convert to Catholicism. Their religion may have changed, but their genetics did not. Some forced converts fled to the Americas after 1492 as Spain conquered the New World. This is how the G2019S variant winds up in Latin America and Brazil.

Using data from 23andMe research participants who consented to participate in this research, 23andMe scientists plotted on a map where those with the LRRK2 variant trace their ancestry.

The maps note the fingerprints of that migration history with the highest concentrations for the mutation in people with genetic ancestry from North Africa, Eastern Europe, Puerto Rico, Cuba, and parts of South America.

“The fact that we see the LRRK2 G2019S variant signal in the Caribbean maps fits with the history of the Jewish Conquistadors who sailed with Columbus on his voyages to the New World,” said Lucy.

We also see strong signals in Brazil, one of the first South American countries to allow Jewish people to live and practice freely.

“(The finding) extends beyond the classic assumption that LRRK2 PD occurs in North African Berbers and the Ashkenazi Jews,” Lucy said. “It is an example of how mutations migrate and can spring up in new founding communities.”

23andMe’s Ongoing Parkinson’s Research

Understanding this history and the significance of a person’s ancestry related to the LRRK2 G2019S mutation and its link to a higher risk for Parkinson’s disease allows researchers to build awareness within these communities.

This, in turn, may help improve how we screen for the disease and how to build a broader community around this specific type of Parkinson’s disease.

The LRRK2 study, known as our Parkinson’s Impact Project, or PIP, has already produced tremendous insights into the disease. It helps scientists better understand the progression of Parkinson’s and how LRRK2 PD differs from idiopathic Parkinson’s, for which there is no known cause.

This study is just one of many aspects of 23andMe’s long-standing commitment to studying Parkinson’s, the second most common neurodegenerative condition behind Alzheimer’s disease.

23andMe researchers have studied the genetic underpinnings of Parkinson’s disease since 2009. More than 30,000 people with Parkinson’s have consented to participate in our research, and more than 196,000 people without Parkinson’s also participate in this specific research.

Those participants have helped 23andMe scientists and our collaborators complete work leading to more than 30 published papers, including 12 since 2020 alone. These studies have also identified almost 100 new genetic variants associated with Parkinson’s disease. It also allows 23andMe scientists and our collaborators to explore in much more detail the role these variants play in the progression of the disease.

The work on LRRK2 G2019S is part of that broader effort. The number of people with the LRRK2 mutation participating in 23andMe research is three times the size of the next largest LRRK2 research cohort. Some of those participating in 23andMe LRRK2 research have Parkinson’s, and others don’t.

As we learn more, we will share more about this study’s relevance to the disease progression and symptoms.

Learn More

None of this work would be possible without those individuals. Those who consented to participate in 23andMe’s research included people with and without Parkinson’s disease.

Learn more about 23andMe’s Parkinson’s disease research here.

The 23andMe’s Parkinson’s Disease Genetic Health Risk Report

You can learn whether you may have an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease based on your genetics through the 23andMe Parkinson’s Disease Genetic Health Risk report.*

The report looks at two specific genetic variants associated with Parkinson’s disease, one in the LRRK2 gene and one in the GBA gene. This report is included in the 23andMe Health + Ancestry Service.

Note

*The 23andMe PGS test uses qualitative genotyping to detect select clinically relevant variants in the genomic DNA of adults from saliva for the purpose of reporting and interpreting genetic health risks. It is not intended to diagnose any disease. Your ethnicity may affect the relevance of each report and how your genetic health risk results are interpreted. Each genetic health risk report describes if a person has variants associated with a higher risk of developing a disease, but does not describe a person’s overall risk of developing the disease. The test is not intended to tell you anything about your current state of health, or to be used to make medical decisions, including whether or not you should take a medication, how much of a medication you should take, or determine any treatment. The Parkinson’s Disease genetic health risk report is indicated for reporting of the G2019S variant in the LRRK2 gene, and the N370S variant in the GBA gene and describes if a person has variants associated with an increased risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. The variants included in this report are most common and best studied in people of European, Ashkenazi Jewish, and North African Berber descent.