By Roslyn Curry*

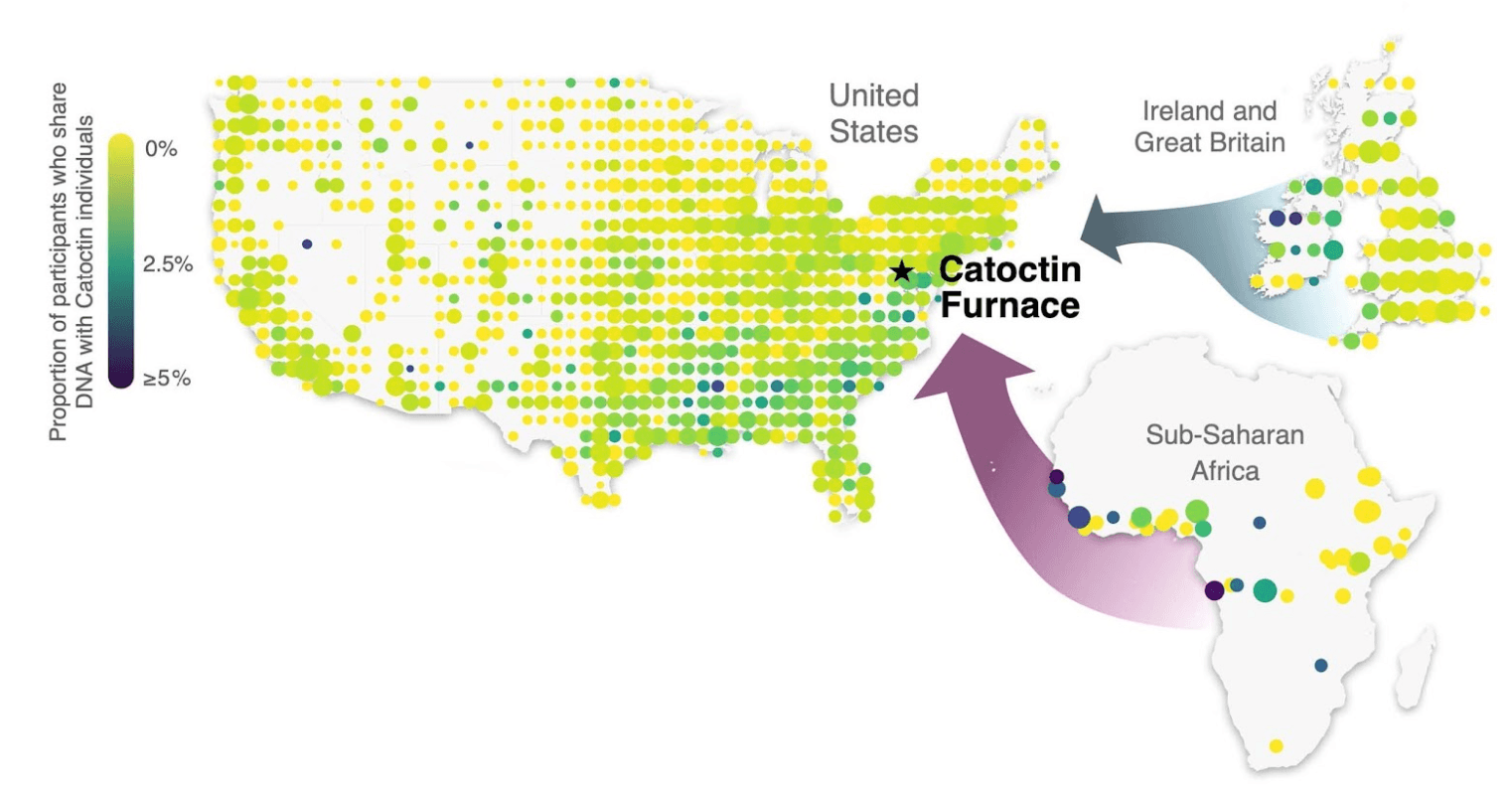

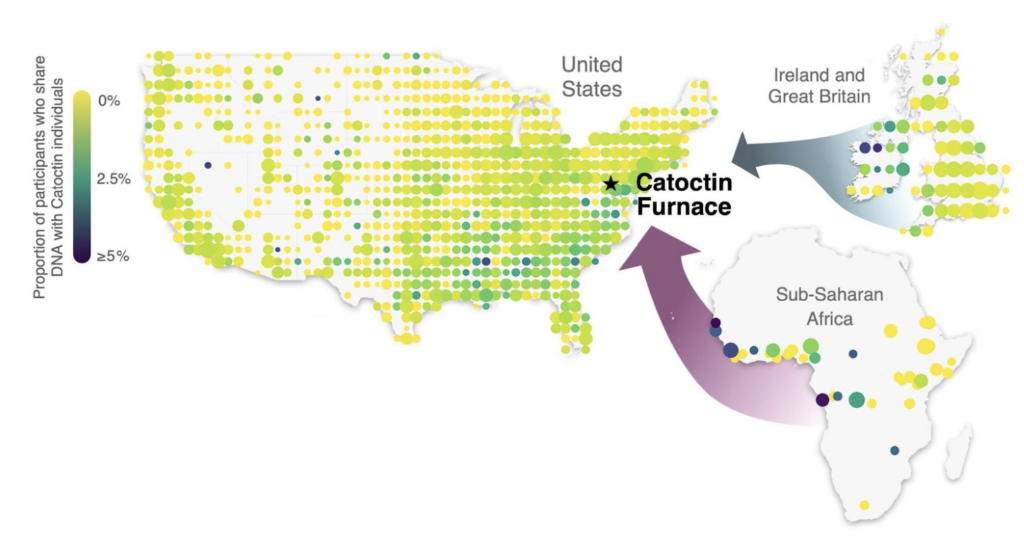

This week researchers at 23andMe, Harvard, and the Smithsonian published a study in the journal Science featuring DNA from 27 individuals of African descent buried in a cemetery at Maryland’s Catoctin Furnace during the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In it, they identified genetic connections between the historical Catoctin people and over forty thousand 23andMe consented research participants.

I joined the study team in 2021 as a 23andMe summer intern to identify ethical and technical aspects of the project that readers might have the most questions about. As a member of the African American and Native American communities, I was particularly excited for this opportunity to learn about community engagement and science communication and to participate in discussions about what measures would be taken to avoid exploitation and other harm to marginalized communities.

If you haven’t already, you can read a summary of the study here. In addition there is a companion paper that looks at the ethical questions in handling historical DNA like this that was published in the American Journal of Human Genetics. Otherwise, please keep reading to learn the answers to the questions I think would be most interesting to readers like you!

Why was this study done?

Ancient DNA and other bio-molecular and archaeological tools offer a way to learn about the lives and legacies of early enslaved and free African Americans, whose history was often omitted from written records.1,2 As part of this study, we developed an approach to identify genetic connections between historical and living people. While this approach could be applied to DNA from any ancient or historical individual to learn about their past, it is a particularly powerful way to help restore information about early African Americans that would otherwise be lost to time.

For this reason, we collaborated with researchers at the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society to learn about enslaved and free African Americans who labored at the furnace in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Our study sheds light on the genetic ancestry of the Catoctin individuals. Moreover it helps pave the way to achieving the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society’s ultimate goal of restoring connections to descendants.

Who gave consent for the Catoctin individuals to be studied?

The forgotten burial ground at Catoctin Furnace was first unearthed in the 1970s during a freeway widening project in Frederick County, Maryland, and the remains were placed in the care of the Smithsonian.

This project was developed in direct response to requests from the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society (CFHS), whose mission is to commemorate, study, and preserve the history of the furnace, including honoring the lives of the enslaved and free African Americans who labored there. They partnered with another local community stakeholder group, The African American Resources Cultural and Heritage (AARCH) Society, whose goal is to tell the story of African Americans in Frederick County, Maryland. When the study began, there were no known people who could trace their ancestry to enslaved or free African Americans who labored at the furnace. Therefore, members of CFHS and AARCH served as a collective kinship community that took responsibility for remembering and honoring the Catoctin individuals. With the support of CFHS and AARCH, the Smithsonian permitted access for their DNA to be sequenced and analyzed.

During the course of the study, researchers at CFHS identified descendants of two African Americans (one free and one enslaved) who labored at Catoctin Furnace by studying historical documents and genealogical data.

Each of these groups plays a key role in the legacy of the Catoctin individuals, therefore we asked for their input, approval and consulted with them during the research process.

How did you match the DNA of the Catoctin individuals with 23andMe research participants?

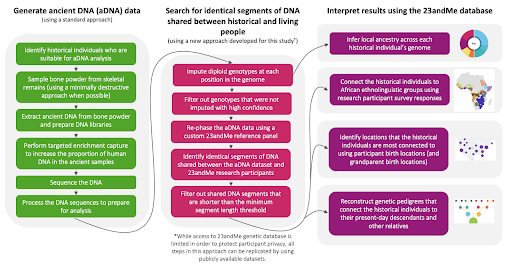

As part of this study, we developed a new approach to search for identical segments of DNA shared between historical individuals and 23andMe consented research participants. These segments of DNA, known as identical-by-descent segments, are inherited from a common ancestor that lived at some time in the past. The more identical DNA that two individuals share, the more likely it is that their shared common ancestor lived recently, while individuals who share only a small number of short DNA segments are likely quite distantly related.

The approach that we developed for searching for these identical DNA segments can be applied to most ancient DNA data, not just that of exceptionally well preserved individuals. Additionally, in order to ensure that other researchers (and amateur geneticists) can use this approach in their own studies, all of the genetic tools that we use in this approach are publicly available.3,4 See the diagram for an overview of the steps involved in our new approach.

What organizations were part of this study, and what were their roles?

This was a collaborative study led by researchers at 23andMe, Harvard University, and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. Since the excavation of the remains of the Catoctin individuals due to road construction in the late 1970s, researchers at the Smithsonian have had the responsibility of caring for them. They helped guide which individuals to sample for ancient DNA based on their preservation and facilitated the interpretation of the results within the context of the historical and archaeological record.

Researchers at Harvard University sequenced the genomes using cutting edge ancient DNA technology and performed the initial population genetic analyses. Then, researchers at 23andMe designed and implemented an approach to compare the DNA of the Catoctin individuals with DNA from over 9 million 23andMe consenting research participants. We also worked with researchers from a variety of other institutions, including the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, who were the first to highlight the need to study the Catoctin individuals further using bio-molecular tools.

Why is 23andMe part of this study?

23andMe was invited to join this collaboration due to their massive genetic database of over 14 million genotyped customers. Over 80 percent of 23andMe customers have consented to participate in research. Data is de-identified and studied in aggregate as part of research.

A database of this size maximized the chance of identifying meaningful genetic connections to the closest living relatives of the Catoctin individuals in the United States, while shedding light on the genetic legacies of those who lived and died at Catoctin Furnace. It also offers details on these individuals’ likely ancestral origins by identifying their distant genetic relatives in Europe and Africa.

What is new or surprising that came from this study?

Despite extensive historical research carried out by the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, we only know of two families who trace their ancestry back to enslaved and free African Americans who labored at the Furnace. The history of the site itself is important because it was among the earliest industrial operations in the United States.5 When we began our study, no one in the local area had any family stories connecting them to Catoctin’s African American community. We were therefore surprised to find that the highest concentration of people with close genetic connections to the Catoctin individuals were born in Maryland (or have four grandparents born there). This strong connection to Maryland suggests that some of the African Americans from Catoctin Furnace stayed in the area after the furnace stopped relying on enslaved labor in 1850.

While stories of family connections to African Americans at Catoctin Furnace may be lost to time, their legacy persists in Maryland through these genetic relatives.

Did you identify any direct descendants of the Catoctin individuals as part of this study?

We identified approximately 42,000 23andMe consented research participants with a genetic connection to Catoctin individuals. The vast majority of these connections are very distant and may even trace back to shared ancestors who lived in Africa (or Europe) before the transatlantic slave trade.

We can tell how likely a person is to be a close relative of the Catoctin individuals based on the amount of identical DNA they share. The more identical DNA segments a person shares, and the longer those segments are, the more likely they are to be a very close relative.6 We considered the 2,975 consented research participants who shared more than 30 cM of DNA (equivalent to ~0.4% of their genome, excluding sex chromosomes) with one of the Catoctin individuals to be a possible close relative. This is the amount of DNA sharing that we expect to observe between people who share a 9th-degree relationship.

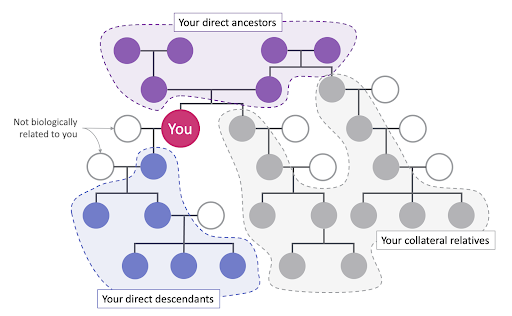

However, more work, including both genetic and genealogical research, is required to distinguish between close relatives who directly descend from the Catoctin individuals and those who share other types of close relationships. These people are often called “collateral relatives.”

What is the difference between a collateral relative and a direct descendant?

Let’s imagine it’s several hundred years in the future. Your direct descendants are people who descend directly from you. For example, your children, your children’s children, your children’s children’s children, and so on, are your direct descendants.

But those won’t be the only people you might share a relationship with in the future. You could also have relatives who are direct descendants of your siblings, (i.e., your great-great-great etc. grand nieces and nephews) and your first or second or third cousins (their descendants would be your first or second or third cousins many times removed). All of these potential relatives who are not your direct descendants are considered collateral relatives. And if those relatives are related to you biologically (i.e., not through adoption or marriage), you may share some DNA.

This is relevant in the case of the Catoctin study because in this analysis, we identified genetic relatives of the Catoctin individuals. However, we expect that most of these relatives are not their direct descendants. This is because over the course of a few hundred years, a person is likely to have many more collateral relatives than direct descendants. And since many of the Catoctin individuals died as children, we know with certainty that any of their genetic relatives are collateral relatives rather than direct descendants, since they were too young to have children.

Can I see if I am related to the individuals buried at the Catoctin Furnace burial ground?

23andMe researchers are exploring the best ways to return results to consented research participants and customers using the approach we developed as part of this study. Since the study of historical individuals unable to give consent, especially those that were enslaved, is highly sensitive. We want to make sure that any results we return are communicated as clearly as possible and in a way that minimizes any potential harm. This is particularly true for people who learn that they share an unexpected genetic connection to the Catoctin individuals.

How might this study help people better understand their ancestry?

As part of this study, we developed a new approach to identify genetic connections between historical individuals and 23andMe consented research participants. This approach can be used by anyone who is interested in identifying genetic connections between historical individuals and living people, including researchers at academic institutions and amateur geneticists. Researchers at 23andMe are directly sharing the results of this study with consented research participants through blog posts and via email.

However, we are still exploring the best way to connect 23andMe consented research participants who have direct genetic connections to these individuals. We have outlined some of the ethical considerations associated with returning results to consented research participants via a direct-to-consumer genetics platform in the American Journal of Human Genetics. Going forward, we hope that this approach will make it possible to identify genetic connections to historical and ancient individuals from across the globe.

Are there people of primarily European ancestry who have been connected to these remains?

Yes. While the Catoctin individuals have primarily African-related ancestry, more than half of them also have substantial European ancestry. While it is impossible to say with certainty the circumstances under which each of the Catoctin individuals came to have this ancestry, we know from historical records that in most cases, African Americans acquired European ancestry as a result of rape of enslaved African American women by their white enslavers and others in positions of power (who had primarily European ancestry).7

In regions of their genomes where the Catoctin individuals have European ancestry, they are likely to share a genetic connection to 23andMe consented research participants who also have European ancestry at this position. Most of these genetic connections are likely to trace back to a shared common ancestor. This would be an ancestor who lived many generations before the Catoctin individuals, possibly in Europe. However, even among consented research participants in the US with over 99% European ancestry we identified people who share large amounts of DNA. This suggests that they may be closely related to the Catoctin individuals. This may mean that they were closely related to the fully European individual from whom the Catoctin person inherited their European ancestry.

We also identified genetic connections between the Catoctin individuals and 23andMe consented research participants whose primary ancestry is European, but who also have some amount of African ancestry. In these cases, the genetic connection may be via a shared European or African ancestor.

What can the Catoctin individual’s maternal and paternal haplogroups tell us about the history of slavery in America?

Three of the 16 genetically male individuals at Catoctin have paternal haplogroups (i.e., DNA from their Y chromosome which is inherited via an unbroken lineage of male ancestors) that are of likely European origin. However, one of the three males also has a maternal haplogroup (i.e., DNA from their mitochondrial DNA which is inherited via an unbroken lineage of female ancestors) that is of likely European origin. This individual has over 50 percent European ancestry and also has a European associated paternal haplogroup. This suggests that most of the Catoctin individuals’ European ancestry was inherited from a fully European male ancestor, rather than a fully European female ancestor.

This finding is consistent with other genetic studies. It supports historical records which show that the European ancestry of African Americans originated largely through a process whereby white men reproduced with Black women as a result of rape.8,9 This gender-based sexual violence contributed to the violent systematic enslavement of African Americans and frequently produced children born into slavery.

Where does ancient DNA come from?

Over the last decade, scientists have searched for the best sources of ancient DNA. They have sampled a variety of historical and ancient remains that might contain traces of DNA. This includes things like hair, bones, even ancient poop!10 What they discovered is that ancient DNA is typically best preserved in bones. Specifically, the petrous bone, which is part of the skull. They aren’t quite sure what makes the petrous bone such a good source of ancient DNA. But it might be because it is so dense or because it develops early and doesn’t grow or change during the course of a person’s life. Other excellent sources of ancient DNA are teeth, hand and foot bones, and long dense bones like those in your legs and arms. But none are quite as good at preserving human DNA as the petrous bone. This is the type of bone we sampled DNA from in this study.

To extract DNA from ancient bones, researchers create bone powder using a handheld drill, mortar and pestle, or even a sandblaster. They then dissolve that powder in special buffers that separate DNA from the other cellular material in bones. When sampling bone powder from the petrous bone (and other bones), researchers try to use methods that are as minimally destructive as possible. In the case of the petrous bone, which near the bones of the inner ear, they have they drill through the base of the skull. This allows for the rest of the skull to remain intact and to appear relatively untouched.11 In this study, we sampled ancient DNA from the petrous bones of the Catoctin individuals and used this minimally destructive approach when sampling from intact skulls.

Were any Black Americans on the research team?

Yes. The research team includes Henry Louis Gates Jr., an American literary critic, historian, filmmaker, and public intellectual who currently serves as the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. You might know him from his television show “Finding Your Roots” on PBS. Linda Heywood, a professor of African History and African American and Black Diaspora Studies at Boston University, was also involved. Both co-authors played a critical role in leading the historical interpretation of the research results. In addition, this FAQ was constructed by a member of the team who is African American.

*Roslyn Curry was a 23andMe intern during the summer of 2021. She is currently a member of David Reich’s lab in the department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, where she will start her PhD this fall.