We don’t know their names, but a new historical DNA analysis by researchers at 23andMe, Harvard University, and the Smithsonian Institution has revealed more about the enslaved and freed African Americans who labored at a Maryland iron furnace just after the founding of the United States. Along with insights into the lives of these forgotten people, the study leveraged 23andMe’s large research database to find connections between these people and more than 40,000 of their living relatives.

The stunning analysis published in the journal Science reveals a hidden history. (You can also find an open access PDF of the paper here.) Moreover, it provides a technical and ethical benchmark to inform future studies of similar, largely forgotten burial sites.

“Our study demonstrates the power of DNA to uncover important history about the lives of people whose stories are lost to time,” said lead author Éadaoin Harney, Ph.D., a 23andMe scientist on 23andMe’s Population Genetics R&D team. “The study revealed more about these individuals, including identifying familial groups, discovering details of their ancestral origins in Africa, and connecting their history to people living today.”

Connections to Early American Industrial Site

The researchers looked at the DNA from the remains of 27 individuals, many of them teenagers and children, excavated from a cemetery at the historic site of Catoctin Furnace. Among them are 15 related individuals clustered into five family groups, which were mostly made up of mothers, their children, and siblings. The remains of those related individuals were generally found buried near one another.

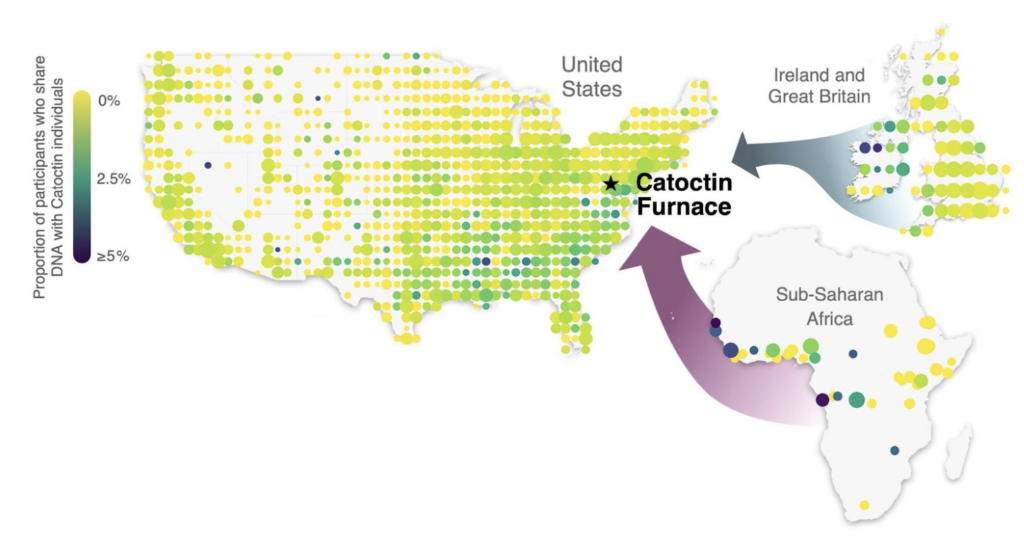

Their DNA indicates that these individuals had more ancestry connecting to a region now known as Senegal and Gambia and, more specifically, groups from that region, such as the Wolof and Mandinka, than do most modern-day African Americans. Many also had European ancestry, mainly from Britain and Ireland, likely due to the rape of enslaved African American women by their white enslavers and others in positions of power (who had primarily European ancestry). Further evidence of that exploitation was that much of the European ancestry was on the paternal side.

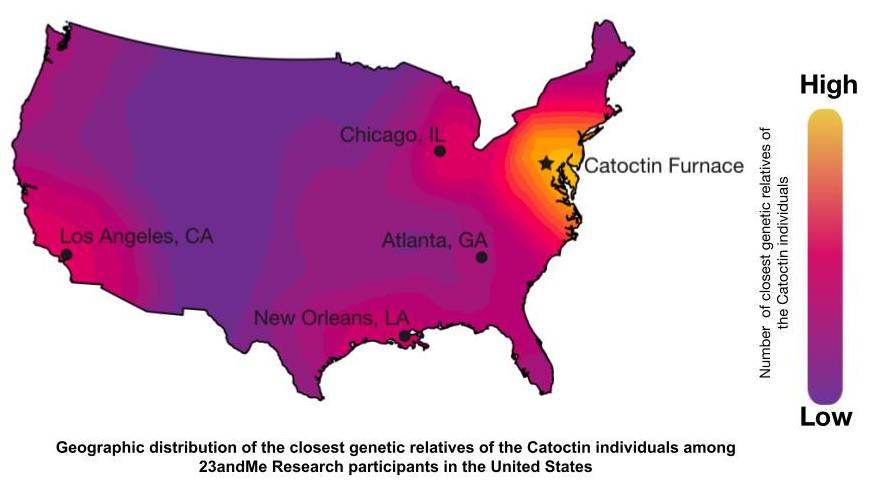

The highest concentration of the Catoctin individuals’ closest living genetic relatives are in Maryland, indicating that some surviving family members of those who labored at the forge remained in Maryland since the late 1700s or early 1800s.

Reconnecting to Lost Roots

Harvard geneticist David Reich helped oversee the study along with Douglas Owsley, curator of Biological Anthropology at the Smithsonian. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History is the custodian of the remains, while scientists at Reich’s lab handled the extraction and testing of the DNA.

“Our study combines for the first time two transformative developments in genomics in the last decade: ancient DNA technology, which makes it possible to efficiently sequence whole-genome data from human remains, and direct-to-consumer genetic databases that contain data from millions of people who have consented to participate in research,” said Reich, co-senior author as well as a professor of genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School and professor of human evolutionary biology in Harvard’s FAS.

“This work demonstrates the power of DNA to provide information about ancestral origins,” he added.

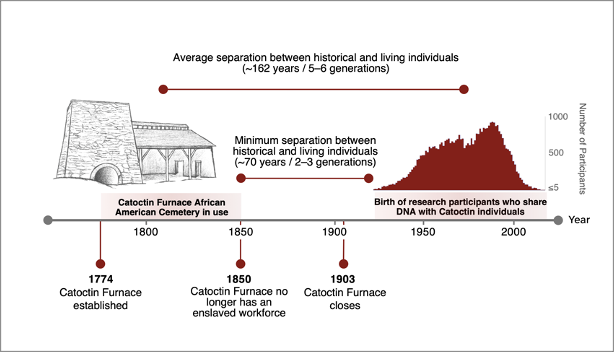

Harney, who completed her PhD in Reich’s lab before joining 23andMe to facilitate this collaboration, and other 23andMe researchers designed and implemented an approach to compare the genomes of the Catoctin individuals with DNA from over 9 million 23andMe customers who consented to participate in research. As a result, the scientists identified more than 42,000 living relatives. Most of these relatives are distant, and a much smaller proportion have a closer relationship. The closest matches were likely 5th-degree relatives, equivalent to a great, great, great grandchild.

Ethical Considerations

Studies like this are extremely delicate, not only because it is sometimes difficult to extract DNA from bones, but also because of the ethical questions this type of genetic analysis raises, especially when it comes to people who lived recently enough that they are almost surely closely related to individuals and communities today. As part of this work, the researchers have outline the ethical considerations in a companion paper published in the American Journal of Human Genetics. In addition, there is an Q&A published on the blog from study co-author Roslyn Curry, a Harvard Kenneth C. Griffin Graduate School of Arts and Sciences student in the Reich lab and former 23andMe intern.

Typically, before work would begin on a DNA analysis like this, scientists would consult with relatives or local communities. But when this study started, there were no known family members of the enslaved people from the Catoctin Furnace site to consult. Instead, the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society consulted with members of the African American Resources, Cultural and Heritage Society in Frederick, Maryland. Later, archival researchers at the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society identified descendants of two African Americans who labored at the site, one free and the other enslaved. These descendant families also were consulted and expressed strong support for the project.

“This study represents a step toward meeting our ultimate goal of identifying a Catoctin descendant community using DNA and other tools,” said Elizabeth Comer of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society.

African American History and Connections

Collaborators on the study also included Boston University’s Linda Heywood and John Thornton, who have extensive expertise on African American history and culture. Also instrumental in the work was Harvard’s Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard and host of the genealogy and genetics TV show Finding Your Roots.

“Recovering African American individuals’ direct genetic connections to ancestors heretofore buried in the slave past is a giant leap forward both scientifically and genealogically, opening new possibilities for those passionate about the search for their own family roots,” said Gates who is also a co-author of the paper.

History Revealed

Like hundreds or thousands of African American burial grounds across the country, the history of those who were buried at Catoctin Furnace could easily have been lost. There were no inscribed headstones, and many of the stones that marked the graves had been moved. The forgotten burial ground at Catoctin Furnace was first unearthed in the 1970s during construction of a new highway in Frederick County, Maryland, and the remains were placed in the care of the Smithsonian.

The history of the iron furnace is well documented. It was founded near a site that was naturally rich in iron ore with an extensive surrounding forest as a source of charcoal. The first owner of the furnace was Thomas Johnson Jr. — a wealthy enslaver, the first non-colonial governor of Maryland, and a signer of the Articles of Association, a precursor document to the Declaration of Independence. Iron production began in earnest in 1776. It contributed in an important way to the arming of the fledgling Continental Army — supplying 100 tons of shells for the Siege of Yorktown.

Early Industrialization in the United States

The furnace grew over time during the early stages of industrialization in the United States. By about 1840, immigrant laborers replaced the enslaved workforce at the facility. While the furnace remained in operation until the early 1900s, the critical contributions of Catoctin’s enslaved and free African American workforce was largely forgotten.

The site serves as an early example of industrialization, and provides an example of the contributions of enslaved people in the early industrial workforce in the United States. Laborers first dug the ore out of the ground, washed it, and then transported it to the furnace on carts. The furnace itself ran nonstop for months at a time. The fires were fueled using charcoal made by burning trees felled nearby, and then burned in large mounds that were tended by “colliers.” Beyond the work related to the furnace, enslaved people also worked in the area as domestic and farm laborers.

In previous studies, anthropologists at the Smithsonian were able to identify physical ailments from which the Catoctin individuals suffered through examination of their skeletal remains, such as a hip deformity that left one young woman with a lifelong limp, a man with a bent and fused spine, and a teenager with multiple, compressed vertebrae, likely due to heavy manual labor. The scientists also found high levels of zinc in the bones of one individual, likely caused by the industrial process of cleaning accumulated zinc deposits from inside the furnace stack.

In this study, DNA analysis found evidence suggesting that three individuals may have suffered from or been carriers of sickle cell anemia, caused by the HbS variant in the HBB gene.

Connecting Families

Connecting these unnamed enslaved people to living relatives, and thereby shedding new light on their ancestral origins and genetic legacy, was only possible with access to a diverse genetic database like 23andMe’s. This study offers additional insight into the genetic legacy of the enslaved and free people who labored at Catoctin Furnace. Combined with a study 23andMe completed in 2020 looking at the genetic impact of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, there is an increased understanding of the impact of slavery on those in bondage, their descendants, and their unacknowledged contributions to American history.