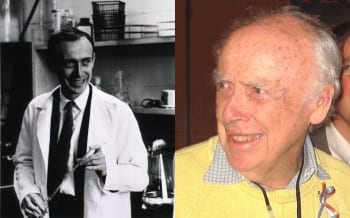

The structure of DNA was first publicly described 55 years ago by James Watson at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) on Long Island in New York.

Personal Genomes Meeting

Thursday night, the now 80-year-old Watson opened up the 2008 Personal Genomes meeting at CSHL by telling the story of the origins of the Human Genome Project, which he headed from 1990 to 1992. In 2003, the Human Genome Project produced a (nearly) complete reference DNA sequence of a human genome that is now essential to basic and applied human genetic research.

These days, Watson pointed out, scientists can read the DNA letters of the double helix so quickly and inexpensively that it is becoming practical to sequence the genomes of large numbers of people. With this progress comes a flood of research questions and technological challenges, and I hope these insights from the lab will translate into advances in personalized medicine.

Bending the Curve in Healthcare Costs

Watson was followed on Thursday night by Francis Collins, who also followed him as director of the Human Genome Project, and later by Mary-Claire King, the renowned breast cancer geneticist from the University of Washington. Collins pointed out that healthcare costs have risen steadily to roughly 20 percent of the US GDP.

How much of this is spent on treatments that might have been identified as unnecessary with the availability of genetic information?

He suggested that widespread genomic sequencing and analysis could lead to the discovery of the genetic causes of common diseases, such as lung cancer and Type II diabetes, for which some genetic links are now known, but much more remains to be learned.

Personalized Medicine

Mary-Claire King considered breast cancer as a case study for personalized medicine. In the case of breast cancer, she noted, there are more than a thousand known mutations in each of the genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 that can predispose a woman to the disease. Many of these are unique to specific families or specific localities — she gave the example of one BRCA mutation endemic to a Norwegian valley.

King illustrated through recent breast cancer studies that linking newly-discovered mutations to disease is a formidable technical challenge, but emphasized that the rewards for succeeding in doing so would be immense.

Roughly 5 percent of new breast cancer cases in the US each year – around 10,000 – are linked to known BRCA1/2 mutations and thus might have been prevented through such measures as prophylactic mastectomy.

Next Gene Sequencing

Friday moved into reports from the trenches. The morning session consisted of talks by researchers from major genome sequencing centers and from the companies behind the so-called “next generation” sequencing methods that underlie this conference.

The new technologies, namely Illumina’s Solexa, 454’s FLX, and ABI’s SOLiD, follow the same general plan as the venerable Sanger sequencing method: scan short fragments, or ‘reads’, of DNA letters, and then reconstruct the original sequence from the reads. They just do it much faster than before, mainly by scanning many reads in parallel.

Much of the concern these days is on the reliability of these new techniques – considering that a single changed DNA letter can mean the difference, for example, between getting Alzheimer’s or not – and so the presentations focused on technical topics like error rates and comparisons across platforms.

New Findings

Even so, there were suggestions that some exciting new scientific findings might be around the corner; Richard Gibbs of Baylor showed early data from their sequencing of a HapMap trio (a father, mother, and child) suggesting that the human mutation rate might be much higher than previously thought. Elaine Mardis from Washington University showed that her lab had found mutations unique to tumor tissue in a lung cancer patient. Known as somatic mutations, they had arisen in the patient during their lifetime and were not found in non-tumorous skin tissue from the same patient. Her study did not show that one of these mutations had actually caused the cancer, but demonstrating that such changes may even be found is intriguing.

The afternoon session moved into the imposing task of storing, processing, and interpreting the flood of data these new technologies generate.

Storing All that Data

Paul Flicek from the European Bioinformatics Institute produced that rarest of things, the funny bioinformatics talk, in describing the travails of dealing with the 100 terabytes (that’s 100,000 gigabytes or 100 million megabytes) generated so far by the pilot phase of the 1000 Genomes Project, and the specter of dealing with a petabyte (1,000 terabytes) of sequence data.

Carlos Bustamante of Cornell described some of the insights into human evolutionary history that have made possible by the DNA deluge, including using sequence data to infer possibly the most detailed models yet of historical human population size and migrations. He also described his lab’s and John Novembre’s recent findings on the relationships between geography and human genetics, a topic we’ve blogged on recently at the Blog here and here.

There’s another big day of talks to come here at CSHL. I’m glad to be here keeping up to date on the latest research so we can incorporate it into 23andMe and show off the site to many people on the cutting edge of genetics.