This week, 23andMe added a new genetic report to help us all be more aware of an often overlooked contributor to health disparities.

Nearly 70% of Black and African Americans have two copies of a variant in the Duffy antigen gene that can cause them to have white blood cell (WBC) counts that are lower than most standard reference ranges.

People who have this genotype — called Duffy null status — do not have an increased risk for infection or other health problems. But they may be flagged incorrectly as having abnormally low WBC counts, which can negatively impact the healthcare they receive.

“I’ve seen patients that are told that they might have cancer, go through painful bone marrow biopsies, miss out on joining clinical trials, or have critical medications like chemotherapy discontinued simply because their white blood cell counts were interpreted without understanding their Duffy status,” says Dr. Lauren Merz, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Division of Hematology/Oncology at the University of Michigan, who is leading efforts to raise awareness about Duffy null status and develop Duffy null-specific reference ranges and who provided expert feedback on 23andMe’s new report.

When a one-size-fits-all blood test falls short

When we have our blood drawn, testing labs use reference ranges to determine whether our results fall in the range considered “normal” or are too high or too low, which can flag the need for clinical follow-up. One common blood test measures neutrophils, which are a type of white blood cell that helps the body fight infections.

Most neutrophil reference ranges are defined based on populations where Duffy null status is rare, such as people with European or Asian genetic ancestry. And blood testing labs don’t usually take into account Duffy status. As a result, nearly 25% of healthy Black and African Americans with Duffy null status — and more than 15% of all Black and African Americans — have neutrophil counts below the standard reference range.

These individuals may be misdiagnosed with neutropenia (low neutrophil counts), which can lead to a number of downstream harms, including unnecessary specialty referrals and follow-up tests like bone marrow biopsies; exclusion from clinical trials (because many trials require a minimum number of neutrophils that is higher than the normal range for people with the Duffy null genotype); and delayed or reduced access to medications for cancer, mental health conditions, and autoimmune disorders. (See the sidebar at the bottom for more details.)

What is the Duffy antigen, and how does it impact white blood cells?

The Duffy antigen is a protein found on the surface of red blood cells and certain other cells in the body. People with two copies of a specific genetic variant in the ACKR1 (Duffy antigen) gene don’t express this protein on their red blood cells — giving rise to the name “Duffy null.”

Being Duffy null can also impact infection-fighting white blood cells called neutrophils. People who are Duffy null tend to have naturally lower levels of circulating neutrophils in the peripheral blood — about 40% lower, on average. But they don’t have an increased risk for infection, because the total number of neutrophils in their bodies remains the same. (Their neutrophils just move from the blood into other tissues like the spleen more easily.)

In the past, healthy people with low neutrophil counts were said to have “benign ethnic neutropenia,” because the Duffy null variant is more common in certain populations. But the preferred name is now Duffy null-associated neutrophil count (DANC), as this refers to the biological driver of Duffy status rather than the social construct of race or ethnicity — and highlights that lower neutrophil counts are normal for people who are Duffy null.

Is Duffy null status associated with any health conditions?

To date, there is no robust evidence that people with Duffy null status are at increased risk for any health conditions. In fact, a recent, large phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) — which looked for potential associations between the Duffy null variant and 1,400 possible health conditions using the National Institutes of Health’s All of Us initiative and other cohorts — did not report any associations with disease. However, this is an active area of research.

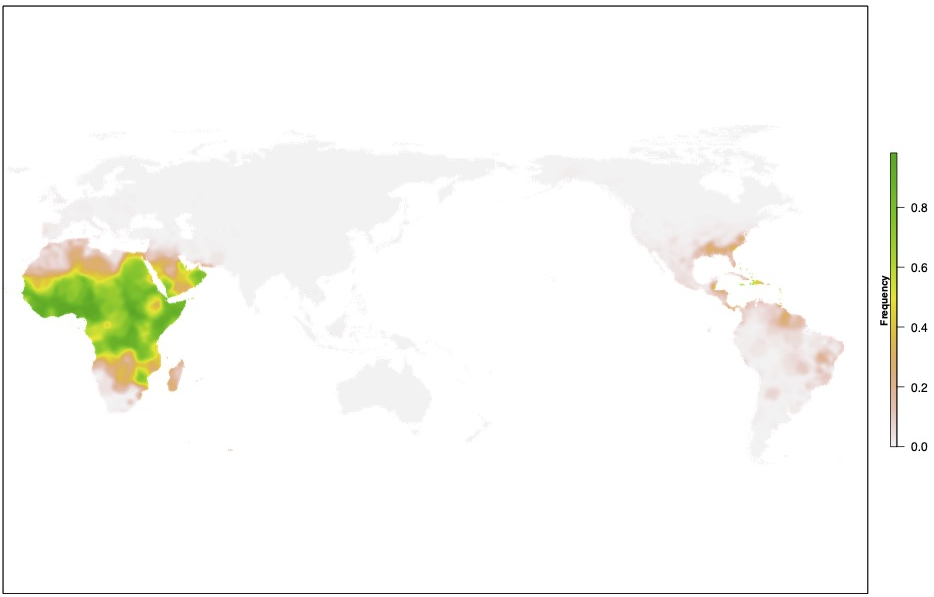

Why is Duffy null status most common in certain populations?

Although anyone can have Duffy null status, it is most common among people with African or Middle Eastern ancestry. In the U.S., two-thirds of people who identify as Black or African American have the Duffy null genotype, which means they do not express the Duffy antigen on their red blood cells.

Scientists believe this variant became common in certain populations because it helps protect against Plasmodium vivax, a malaria parasite that relies on the Duffy antigen to infect red blood cells. (The variant does not protect against other types of malaria.) Over generations, people in regions where this malaria parasite was widespread were more likely to inherit this protective variant, and it remains common today in people with ancestry from some malaria-endemic regions.

The importance of raising awareness

Last year, the American Society of Hematology (ASH) launched the Absolute Neutrophil Count (ANC) by Duffy Status Project, aimed at creating specific neutrophil reference ranges for people with the Duffy null genotype and advocating for broader awareness and testing.

“The Duffy null genotype is a perfect example of how well-meaning systems can fall short when they don’t reflect the full diversity of the people they serve,” says Dr. Merz. “Raising awareness — among both clinicians and patients — is essential to prevent misdiagnosis and ensure more equitable and personalized care.”

You can become your own advocate by learning about your Duffy status and sharing that information with your doctor.

The White Blood Cell Count (Duffy Antigen-Related) report is available to 23andMe+ Premium™ members with their other Wellness reports.

A deeper dive: How lack of awareness of Duffy null status can lead to downstream harm

Although Duffy null status does not usually cause health problems, harms can arise when Duffy null individuals are misdiagnosed with abnormally low neutrophil counts. These harms can include:

-

Unnecessary follow-up testing. In general, low neutrophil counts can prompt concern from doctors, because they can be caused by blood cancers like leukemia. Follow-up testing involves a bone marrow biopsy, which is an invasive and sometimes painful test.

Because their neutrophil counts may be naturally lower than standard reference ranges, people with Duffy null status are much more likely to receive unnecessary bone marrow biopsies. And one study reported that Duffy null status was the most common reason for children to be referred to a children’s hospital for low neutrophil counts. -

Exclusion from clinical trials. Many chemotherapy drugs reduce WBC production, which can make patients more susceptible to infections. As a result, most cancer clinical trials require patients to have a minimum neutrophil count before starting the trial, to help keep patients safe.

But a recent study found that more than 75% of cancer clinical trials have neutrophil thresholds that exclude some people with Duffy null status. Researchers have suggested these exclusion criteria may be one reason that Black Americans are less likely to be included in cancer clinical trials. -

Delayed or reduced access to medications. Because some medications reduce WBC production, patients often have their neutrophils counted before and during treatment, so that their clinicians can adjust the dose, delay the start of treatment, or discontinue medications if counts become too low.

Because people with Duffy null status tend to have lower starting neutrophil counts, they may experience reduced or delayed access to important medications for cancer, mental health conditions, and autoimmune disorders, or inappropriate dose adjustments. Because chemotherapy dose often increases the chance of survival, some scientists think that inappropriate chemotherapy dosing related to Duffy null status could help explain, in part, why breast cancer mortality is higher in Black than white Americans.