Recently we chatted with Bill Vick, founder of PF Warriors, a non-profit group for people living with pulmonary fibrosis, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

A Rare Disease

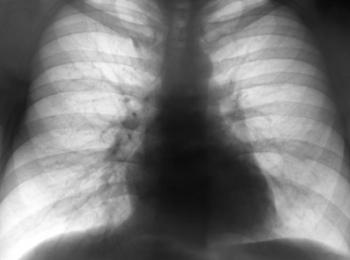

Being diagnosed with IPF, as with many other rare diseases, can feel both overwhelming and bewildering. For many, the first time they’ve heard about the condition is when they get a diagnosis. IPF results in irreparable scarring of the lungs, which progressively worsens lung function. It’s terminal, and there is no cure. But there is some promising research underway, and last year, 23andMe launched a genetic study of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. We connected with Bill and PF Warriors through that work.

Bill’s journey might explain the use of the word “warrior” in naming the group. Before a career as a serial entrepreneur — heading up large sales divisions, launching computer software companies, and creating his own executive recruiting firm — Bill was a Force Recon Marine. After he retired from business, he became a competitive masters division athlete and brought that same kind of intensity first tapped into as a Marine and then cultivated working in the corporate world. To prepare for competition he included daily runs, swims, weight lifting, or workouts in the gym. It was while training for a competition that he noticed his swim times dropping. He also noticed that he sometimes had difficulty catching his breath.

It took a while to get a diagnosis, and when he did, it was jarring. He had never heard of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis before, and he didn’t know how he got it. (Idiopathic means no known cause.) And he was told there was no treatment. So after coming home from the doctor that day, he and his wife Patti decided that he should get his affairs in order, and then the two of them could knock off their “bucket list” of things to do while Bill still could. So they celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. Bill was 72 at the time. He thought he only had two or three years to live.

But that was ten years ago.

What are some of the common themes you’ve heard from people about first getting diagnosed?

I, like many, was diagnosed by chance as I had a cough, weight loss, and shortness of breath that my family doctor could not explain. And you know, if I hadn’t been training so hard and been so in tune with minor changes in my body, I might not have noticed.

I was 72, but I was an active triathlete, and I’d been a competitive jock all my life. I was training for a short course race here in Texas and started noticing my swim times dropping. So I went to my doctor, and he thought it might be athletic asthma or bronchitis or COPD, and gave me an inhaler, and then a nebulizer. But that didn’t help much. I think that went on for about a year before I went to a pulmonologist. They did a high-resolution CT scan and a biopsy.

When the results were in, they called and told me to come in and bring my wife, Patti. So we were ushered into a small waiting room, and the doctor comes in and says:

“You’ve got a rare disease, IPF. It’s a lung disease with no cure and nothing to stop it. You should go home and get your affairs in order.”

Why are so few people, including doctors, aware of IPF?

Well, it’s a rare disease. I think my doctor had seen maybe one or two other people with it in his whole career. So when I got my diagnosis, there just weren’t many resources out there to find out more. And that’s one of the reasons we started PF Warriors. As I talk to other patients and groups, the same kinds of questions come up. That’s why it helps to hear from others who are going through the same thing. We now have 2,400 members worldwide and are located in 19 countries.

It took me a couple of years, but I got to this point that I wasn’t saying that I’m dying from this disease, but that I’m living with it.

Typically, the survival rate after diagnosis is two to three years. You got your diagnosis a decade ago. How have you been able to do so well for so long?

My advantage was that I was a competitive athlete attuned to my body. So not only was I in great shape but I got diagnosed perhaps earlier because I very quickly noticed the changes in my body.

But we don’t really know a lot about this disease. There’s still a lot of ignorance out there, and that’s why we need more research. I’ve also benefited by being one of the first people prescribed Esbriet® (pirfenidone). I started taking that when I was 75, and it can help slow the scarring of your lungs or progression of pulmonary fibrosis.

A few years ago I talked to a woman who was a fellow IPF patient named Peggy and I asked her about how long I had to live. She said something about hearing the diagnosis of dying in two or three years and she smiled and said:

“When you can find the expiration date that God tattooed on your bottom, believe it, but until you do, take each day as it comes and live it fully.”

Bill Vic

What do you think is the biggest value of having an organization like PF Warriors?

It’s meeting people like Peggy in Florida with something to say, but it’s also crowdsourcing information with others, having a place where you can go for information or questions or support. You know, if you have a doctor who you talk to, that’s a certain channel for information but talking to someone like you who has it, it’s a different kind of conversation.

Recently you invited 23andMe’s John Matthews to speak to your group. He is the Senior Clinical Development Leader for Therapeutics at 23andMe. He is also a physician who trained in pulmonary medicine. Why did you ask him to speak, and what did he share with you?

John discussed 23andMe’s work in drug discovery and 23andMe’s ongoing effort to recruit 1,000 people for a genetic study on IPF. As a result, we’ve had other researchers and leading scientists in the field to talk. It’s a way for us to stay informed and keep ahead of the curve. John walked through the role genetics plays in disease and how 23andMe uses genetic information and other information to find potential drug targets. He also answered a lot of questions from our members who participated in the discussion.

What are your thoughts about the potential for finding new treatments?

I think studies like this, using genetics, are critical. But it isn’t easy to get enough people (with IPF) to participate. This is a similar problem with clinical trials, simply finding people willing to participate, but you need people if you want to see significant breakthroughs. I’m hoping we can help 23andMe with that. I’m optimistic that we will find a cure and treatment, maybe I won’t be around to see it, but I want to do whatever I can to help.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]