Researchers often say it’s their love of science that drives their work, but for Eric Minikel and Sonia  Vallabh it’s their love that propels the science.

Vallabh it’s their love that propels the science.

The married couple – both are researchers at the Broad Institute and are completing their doctorates at Harvard Medical School – helped to co-author a new paper looking at the genetic risk for developing prion disease, a rare but devastating condition that hits the nervous system, impairs brain function, triggers other neurodegenerative symptoms such as memory loss and insomnia, and ultimately causes death. It’s triggered when a protein misfolds causing clumping in brain tissue, typically manifesting itself around the age of 50.

It’s Personal

For Eric and Sonia this research is personal, as Eric movingly writes in this blog post.

About five years ago, not long after they married, their lives took a sharp turn when Sonia’s mother died at 52. It was only after her mother passed away that Sonia and Eric learned about what killed her – Fatal Familial Insomnia, a form of prion disease. Soon thereafter, Sonia learned that she inherited a genetic mutation, putting her at a very high risk for the disease.

In response, first Sonia, who’d recently graduated from law school at Harvard, and then Eric, a city planner and software engineer, made career changes, dedicating their lives to finding a cure for prion disease. They started working at a lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, took night courses and eventually were accepted at Harvard Medical School. They now work in the Stuart L. Schreiber Research Laboratory at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

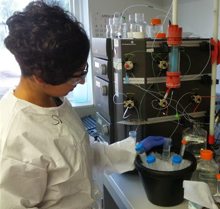

Sonia working in the lab.

Even before this paper they made an impact. A few years ago, the couple formed the non-profit Prion Alliance and Eric started the blog CureFFI, which is a great resource for information about research into prion disease. It also catalogues his education in the science and what motivates him.

Recognition for their Work and Story

Their story has been featured in both the Atlantic and the New Yorker. A joint presentation they did at the American Society of Human Genetics focused on citizen science and crowdsourcing for scientific research.

More recently, Eric developed a statistical method that refuted previous studies suggesting that in families with inherited prion disease, the disease will manifest itself as much as 14 years earlier with each generation. If true that would have been devastating for Sonia, who turned 31 in 2015. However, Eric’s findings also highlight problems with research into other rare diseases, which can suffer from a lack of data or selection bias because the data comes from within the disease communities they study.

The research for this paper – which draws in part from data provided by 23andMe and Exome Aggregation Consortium data from the Broad – is important because it changes assumptions about the risks associated with some of the more than 60 mutations in the PRNP gene that are thought to confer risk for prion disease. In another recently published paper, Harvard’s Robert Green points out that Eric and Sonia’s work doesn’t just shed light on prion; it also highlights the power of sharing genetic data:

“The story of this research stands as a testament to the generosity of unrequited data sharing from thousands of individuals and scientists around the globe and to the unflinching devotion of a young couple to alter their seemingly unalterable genetic destiny,” Green writes.

Real Progress

The study began with the observation that variants in the PRNP gene that have been reported to cause prion disease are at least 30 times more common than expected in the general population. Up until now, many doctors have assumed that all those mutations were associated with a 100 percent risk of developing the disease. However, if all of these mutations were “completely penetrant,” or 100 percent disease-causing, then the number of people developing the disease each year would have to be much higher than what is seen in clinics worldwide. This discrepancy suggested to the researchers that some of these variants could have “incomplete penetrance” or may even have no impact on the disease risk.

By comparing the frequency of individual variants in prion disease patients versus the general population, the team found that the variants previously reported to cause prion disease aren’t all created equal — they actually form a spectrum of risk. At one end, some mutations previously reported as disease-causing appear benign, meaning that they do not increase the risk of prion disease above the baseline risk in the general population.

Variants with Different Risk

On the other end, some mutations really do convey a very high risk, upwards of 80-to-90 percent, of developing disease in one’s lifetime. In between, some variants appear to convey an intermediate lifetime risk of, for example, 0.1 or 10 percent. Then, there were some variants for which the data was insufficient to draw conclusions.

According to the researchers, this is great news for some individuals who carry variants that now appear to be low-risk.

“Through our relationship in the patient community, we have met people with several of the mutations that we now believe are low-risk or benign. Some of those people had been told they had a very high risk of disease, so our work changes their prognosis,” said Eric.

Unfortunately, Sonia’s mutation, D178N, isn’t one of those that is low-risk. The new research confirms that the mutation she carries—along with mutations that many others carry—confers a near 100 percent risk for developing prion disease.

“Our work doesn’t change the prognosis for most patients with genetic prion disease,” said Eric. “Only a minority of them.”

Although it doesn’t directly change Sonia’s prognosis, the new study may help develop drugs to treat prion disease. The study found that a few reduce the prion protein’s function among the benign mutations. Because carriers of these so-called “loss-of-function” mutations are apparently healthy, it suggests that developing drugs that work against the protein may be safe. Eric and Sonia are now working on developing molecules to do just that, and they can move in that direction more confidently.

Love and Science

In the context of prion disease, this study positively impacts the prognosis for a few hundred individuals worldwide while providing validation for a therapeutic strategy that may offer hope more broadly to patients and families affected by prion disease.

The researchers said that, more generally, the study also highlights the value of large reference datasets like 23andMe’s and Broad’s.

For this study, researchers used exome data from 60,000 people collected by the Broad Institute from a large international consortium and genotypic data from more than 530,000 23andMe customers who consented to research. Excitingly, as datasets of this size continue to grow, so will their power to expand and refine our understanding of human disease.

In the couple profile that appeared in the New Yorker in 2014, the writer quotes from an email he received from Sonia trying to describe her relationship with Eric.

“I thought when I married him that I could never love anyone more than I did that day. But I was wrong,” she said. “We are in a new dimension of partnership now, and I am more in love and, frankly, more in awe of him with every day we spend together. His brain is outstandingly powerful, and I see things I would never have known he was capable of in any other way. He was meant to do this work, and the world will be better for it.”

Love might not conquer all, but Eric and Sonia’s work points to what it can do when fueling the work of two brilliant minds.