Researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and 23andMe have found possible clues to why older mothers face a higher risk for having babies born with conditions such as Down syndrome that are characterized by abnormal  chromosome numbers.

chromosome numbers.

Published in the journal Nature Communications, the study looked specifically at patterns of recombination among more than 4,200 families, who are 23andMe customers and have consented to research. The study showed that the normal process by which parental chromosomes are recombined before they are passed onto children appears to be less regulated in older mothers.

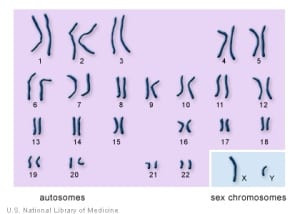

Recombination is a cellular process that is vital in maintaining genetic diversity. During recombination, chromosomes from parents are shuffled to create a unique combination of genetic traits. These shuffled chromosomes are then passed on to children during reproduction. It is also during recombination that errors can occur. For example, children may inherit chromosomes with rearrangements or an abnormal number of chromosomes.

In this study the researchers verified that the rate of recombination increases with the age of the mother. But they also found that recombination appears to be less regulated in older mothers, which may explain the higher risk for abnormalities in their children.

“It’s been known for many years that the rate of recombination varies across the genome, but less is known about how the rate of recombination changes with parental age,” said study leader Adam Auton, Ph.D., assistant professor of genetics and of epidemiology & population health at Einstein.

Looking deeper into the recombination process in older parents, the researchers found for the first time that the spacing between recombination events occurring on the same chromosome becomes less constrained as women age. For older mothers, more recombination events occur in close proximity to one another, providing evidence that the tightly regulated process of recombination becomes less regulated with increasing maternal age. By contrast, no such age-related effects were observed in

23andMe Statistical Geneticists

fathers.

While the paper does not currently have any clinical application, it does add to our understanding of recombination as a basic biological process, said 23andMe Statistical Geneticists Nick Furlotte, one of the paper’s co-authors.

“Recombination is one of the fundamental biological processes thats helps to drive human evolution,” said Nick. “This study is a great example showing how using 23andMe’s large cohorts and a data-driven approach can lead to a further understanding of our basic biology.”