As we celebrate Black History Month, we want to raise awareness about some of the conditions 23andMe reports on that are more common in people of African descent.

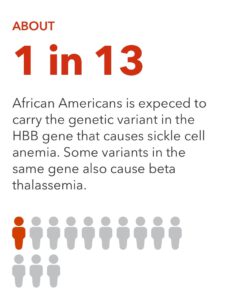

Sickle Cell Anemia

About 1 in 13 African Americans have the genetic variant in the HBB gene that causes sickle cell anemia. Sickle cell anemia is characterized by anemia, episodes of pain, and frequent infections. Being a carrier does not mean you have the condition. A person must carry two variants in the HBB gene to develop this condition.

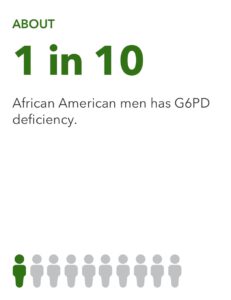

G6PD Deficiency

About 1 in 10 African American men have G6PD deficiency. People with this condition usually don’t develop symptoms unless they are exposed to certain triggers, including certain food, medications or infections.

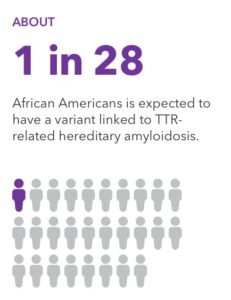

Hereditary Amyloidosis (TTR-Related)

It is estimated that about 1 in 28 African Americans carry a variant linked to TTR-related hereditary amyloidosis. This little-known genetic condition is caused by the buildup of a protein called transthyretin (TTR). This protein buildup can damage the nerves, the heart, and other parts of the body. Because the symptoms vary widely, the condition is often misdiagnosed.

Beta Thalassemia and Related Hemoglobinopathies

Beta thalassemia is a genetic disorder characterized by anemia and fatigue as well as bone deformities and organ problems. Among those who are most impacted are people of North African descent.

23andMe Health + Ancestry Service customers can learn more about these conditions by viewing their health reports.*

African Americans continue to be underrepresented in genetic research, but 23andMe is working to change that with initiatives to improve the diversity in the science we do.

Our mission has always been to help people access, understand and benefit from the human genome. We want to make sure that we’re doing that for all people. That means broadening the diversity and including populations that are not now well represented.

Diversity in Research

For more than a decade now, 23andMe scientists have undertaken efforts to improve diversity in our research, particularly among African Americans and people of African descent. Some of those efforts include programs like our Roots Into the Future study, the African Genetics Project, and the recently completed African American Sequencing Project.

23andMe now has one of the largest, if not the largest, cohorts in the world of genotyped and phenotyped African Americans who have consented to participate in research. This offers incredible potential to make new findings relevant to people with African ancestry. It has already allowed our scientists to conduct genome-wide association studies specific to people with African ancestry into such things as uterine fibroids and alcohol and tobacco use.

23andMe now has one of the largest, if not the largest, cohorts in the world of genotyped and phenotyped African Americans who have consented to participate in research. This offers incredible potential to make new findings relevant to people with African ancestry. It has already allowed our scientists to conduct genome-wide association studies specific to people with African ancestry into such things as uterine fibroids and alcohol and tobacco use.

But we want to do more, so beyond the work, we and our collaborators have done, 23andMe is also working to improve research diversity more broadly.

Last year, we have made available the de-identified data from 23andMe’s African American Sequencing Project through the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s database of Genotypes and Phenotypes (dbGaP). Participants in this project were asked for an additional layer of consent beyond 23andMe’s normal research consent process.

We’ve made great strides but we still have a long way to go. Learn more about 23andMe’s research here.

*The 23andMe PGS test uses qualitative genotyping to detect select clinically relevant variants in the genomic DNA of adults from saliva for the purpose of reporting and interpreting genetic health risks and reporting carrier status. It is not intended to diagnose any disease. Your ethnicity may affect the relevance of each report and how your genetic health risk results are interpreted. Each genetic health risk report describes if a person has variants associated with a higher risk of developing a disease, but does not describe a person’s overall risk of developing the disease. The test is not intended to tell you anything about your current state of health, or to be used to make medical decisions, including whether or not you should take a medication, how much of a medication you should take, or determine any treatment. Our carrier status reports can be used to determine carrier status, but cannot determine if you have two copies of any genetic variant. These carrier reports are not intended to tell you anything about your risk for developing a disease in the future, the health of your fetus, or your newborn child’s risk of developing a particular disease later in life. For certain conditions, we provide a single report that includes information on both carrier status and genetic health risk. For important information and limitations regarding other genetic health risk reports and carrier status reports, [visit https://www.23andme.com/test-info/] [click here].