By Samantha Ancona Esselmann, PhD, product scientist at 23andMe

(Warning: This story contains Star Wars spoilers.)

Hopeless romantics, myself included, wait with bated breath for the final installment of the nine-episode-long saga of the rise and fall (and rise again) of the Skywalker dynasty. It’s not because we care what happens to the Resistance or to the First Order or even what happens to some of our favorite supporting characters. (But if Chewbacca dies, I walk.)

No, we’re really here for “Reylo.”

A portmanteau for the ages, “Reylo” combines “Rey” — the name of the Resistance’s scrappy heroine — with “Kylo” Ren, aka Ben Solo, the troubled space boi who kills his dad. Star Wars episodes seven and eight tease a possible romantic connection between the two characters. Sparks fly during a series of intimate Force-chats, which we later discover were orchestrated by Kylo’s boss, Snoke.

Some fans love to ship “Reylo,” while others love to hate it. With Episode 9 just around the corner, long-dormant “Reylo” Reddit threads, fanfic forums, and Twitter memes are waking up, and I’m reminded that many of us are pondering the same question that’s at the heart of Episodes 7–9: Are Rey and Kylo related?

Kylo Ren is the son of Leia Organa. Luke Skywalker’s sister, while Rey’s mysterious parentage and her natural aptitude with the Force hint at familial ties to the Skywalker dynasty. (What’s her midichlorian count, anyway?)

So, what if — as many hypothesize — Rey is actually Luke Skywalker’s daughter, secreted away on a remote desert planet.

This would make Rey and Kylo first cousins. If Rey and Kylo are cousins, and if they were to have children together, their children would only have six great-grandparents, instead of the expected eight. There would be a closed-loop in their recent family tree.

So, is that… bad?

Well, acknowledging that cousin marriages are common and often encouraged in many parts of the world, we can answer this question with science!

Inbreeding: the background

Inbreeding is when two closely related individuals, who inherited some identical segments of DNA from the same ancestor(s), have children. The term genetic counselors typically use for inbreeding is “consanguinity,” which means “of the same blood” and is pronounced “con-san-gwinity.”

The degree of relationship between the two individuals matters a lot. Children of parents who are brother and sister are more consanguineous (“con-sang-win-us”) than the children of two people who are first cousins. For similar reasons, consanguinity within the same family over multiple generations increases the risk for hereditary disorders more than one isolated instance of a consanguineous union in a family tree.

Everyone’s family tree is full of these “closed loops,” but they’re usually much bigger loops than those typically associated with consanguinity.

How do we know that?

As we look further and further back in our family trees, the number of ancestors in a given generation grows exponentially. We have four grandparents, eight great-grandparents, and over 1,000 10th great-grandparents. Following this logic back, we’d have more than a trillion ancestors just 40 generations ago. But that’s more than 10 times the number of humans to have ever lived — i.e. it’s impossible. No matter how you slice or dice it, the numbers just don’t add up the way we’d expect, and it’s because of a phenomenon called “pedigree collapse.”

If you go far enough back in time, your family tree is collapsing in on itself over and over again. Many of your ancestors will show up on multiple branches in your family tree, forming “loops.”

What does evidence of recent inbreeding look like in someone’s DNA?

People inherit 23 pairs of chromosomes: one set from mom and one from dad. Therefore, we generally have two copies of every chromosome…two copies of every gene, and so on.

This comes in handy when one of the copies is broken. It’s also why humans reproduce by having sex. The ability to mix and match slightly different versions of the same genes through genetic recombination helps human populations adapt to new environments and protects us against disease.

For the most part, the DNA in both copies is the same, differing at only a handful of spots.

A stretch of completely matching DNA on both copies of a chromosome is called “homozygous,” meaning “same gene,” while a stretch of DNA with a few differences between the copies is called “heterozygous” (meaning “different gene”).

And, if there’s evidence of consanguinity in your recent family history, you are more likely to have stretches of homozygous (identical) DNA than someone who does not.

So how can we measure consanguinity?

To quantify consanguinity, scientists look at how much of someone’s DNA is predicted to be completely identical based on their family tree.

It’s called the coefficient of inbreeding, and it’s a fairly simple calculation that outputs a score between 0 and 1, where 0 is good and 1 is, well, bad.

In basic terms, someone’s coefficient of inbreeding is half of the degree of relationship between their parents, where the parents’ relationship degree is also measured in a range from 0 – 1, based on how much DNA they share.

If the parents are completely identical clones of each other, then their relationship degree is 1, and the offspring’s inbreeding coefficient would be half that, or 0.5. (This basically means that on average, 50 percent of the offspring’s DNA would be homozygous.)

But, in real life, humans can’t mate with their clones. (Although, all bets are off in the Star Wars universe.)

So, what about Kylo and Rey — possible Skywalker cousins?

First cousins share an average of 12.5 percent of their DNA. If first cousins, Kylo and Rey, had a child, that child would have an inbreeding coefficient of 0.0625 (0.125/2) This means that roughly 6.25 percent of their child’s DNA would be made up of identical copies from parents Kylo and Rey (which they inherited from their grandparents, Padmé and Anakin).

Turns out, an inbreeding coefficient of 0.0625 is quite low, at least compared to some individuals in highly inbred families, such as the Spanish Habsburg.

The Habsburg monarch estimated to be the most inbred was the 17th-century Spanish King, Charles II, whose inbreeding coefficient was estimated to be more than 0.25.

But even for an inbred family like the Habsburg, it only takes one generation of having children with somebody genetically unrelated to reset the proverbial consanguinity meter in any children resulting from that union.

So where does that leave us with Reylo?

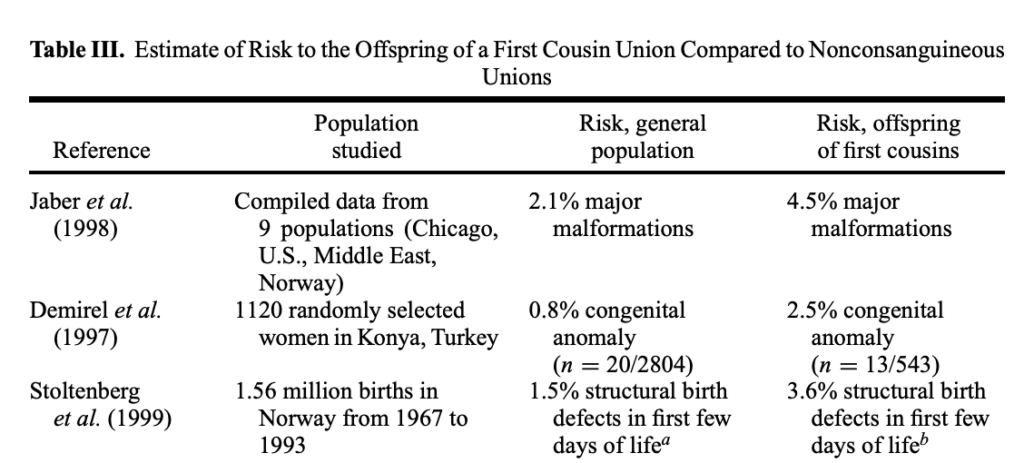

Assuming Rey is a secret Skywalker (and assuming DNA works the same way in the Star Wars universe), “Reylo” would not be all that unusual. Any children they may have together would only be at slightly higher risk for congenital abnormalities compared to children of non-consanguineous unions. According to a 2002 report published by the National Society of Genetic Counselors (the NSGC):

“Romantic relationships between cousins are not infrequent in the United States and Canada, and these unions are preferred marriages in many parts of the world. The offspring of first-cousin unions are estimated to have about a 1.7– 2.8 percent increased risk for congenital defects above the population background risk.”

Table excerpt from “Genetic Counseling and Screening of Consanguineous Couples and Their Offspring: Recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors” (2002).

The report’s authors also emphasize:

“There is a great deal of stigma associated with cousin unions in the United States and Canada that has little biological basis…Health providers should provide supportive counseling to these families and respect cultural belief systems. The psychosocial issues for genetic counseling in the case of a cousin union are very different from those for an incestuous union.”

So that’s it for Science vs. Star Wars. We’ll probably learn more about Rey’s ancestry in The Rise of Skywalker. Odds are, Kylo and Rey are unrelated, anyway.

If you’ve discovered evidence of unexpected relationships in your family tree, our customer care team has created a resource for you here. A version of this story can be viewed here, on The Startup.