Researchers may have identified a genetic reason for why some people are more susceptible to chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus than others.

Whenever a person contracts a virus, the immune system is usually able to clear the infection from the body completely. But more than 400 million people worldwide have a chronic form of hepatitis B that remains in their livers and puts them at risk for cirrhosis and liver cancer.

Age at infection is one of the most important factors in determining whether hepatitis B will become chronic. Most people infected with hepatitis B after the age of five are able to fight it off, but the majority of those who are infected as infants or very young children never get rid of the virus. In a new report, scientists show that variations in an immune system protein may also contribute to whether a person will end up with chronic case of hepatitis B. These results, published online today in the journal Nature Genetics, may help scientists understand more about the how hepatitis B causes disease and could someday facilitate the development of new treatments.

Researchers analyzed the DNA of more than 2,000 people with chronic hepatitis B and more than 4,000 controls from Japan and Thailand. Two genetic variations showed significant associations with the condition. For both, each copy of an A reduced the odds of chronic hepatitis B infection by about 40%.

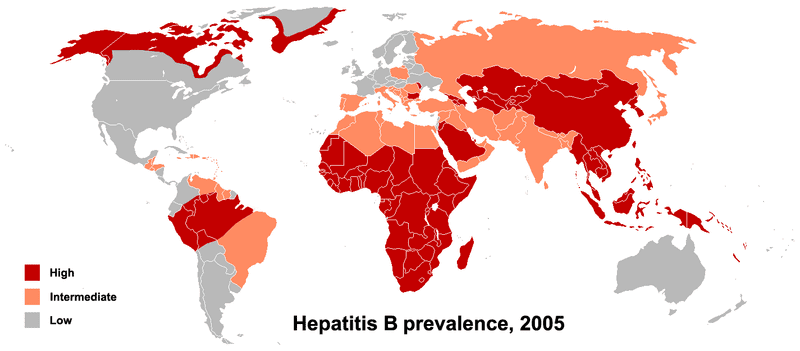

The researchers note that the protective A versions of the SNPs tend to be found at lower frequencies in areas with high rates of chronic hepatitis B. While the scientists don’t contend that genetic factors are the sole determinants of disease prevalence, they do suggest that these factors might exert a substantial influence.

The genes in closest proximity to the two identified SNPs, HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1, encode subunits of an immune system protein called HLA-DP. Upon further analysis, the researchers found that variations in the HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 genes also affect the odds of chronic hepatitis B infection.

HLA-DP is one of several proteins that help alert the immune system to the presence of infections. The authors of the study suggest that changes in this protein might affect its ability to signal the immune system and could therefore result in a weak, or even completely absent, immune response to hepatitis B infection. This, in turn, could lead to persistent infection with the virus. In support of this idea, previous research has shown that some versions of the HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 genes affect the immune system’s response to the hepatitis B vaccine.

Map Image: PhillipN

Notes:

- Box size is relative to chronic hepatitis infection rate. Rates were determined by taking the average of the rates given by the authors of this study for each population. These are only estimates.

- Color indicates the frequency of the A version of or . Lighter colors indicate lower frequencies.

- Populations are broad categories: Asian, African, European, Central American

- Subpopulations are HapMap3 populations

- Information can be recategorized by changing order of the population and subpopulation icons at the top of the graphic.