Previously we discussed two papers that identified genetic variants associated with hemoglobin levels in circulating blood.

But blood consists of much more than hemoglobin. It is responsible for much more than just transporting oxygen. This week Nature Genetics published the results of two of the largest blood studies to date. Together the studies identified dozens of new variants associated with nine blood-related traits.

Cellular Components

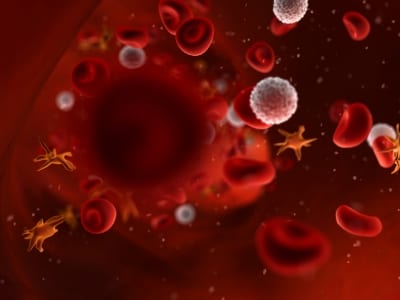

In addition to red blood cells, which carry hemoglobin, whole blood contains white blood cells. White blood cells are a crucial part of our immune system. Whole blood also contains platelets, which are important for clotting. All of these cellular components are suspended in a protein-rich plasma that makes up most of the volume of blood, and maintains the pressure needed to deliver the blood’s cargo throughout a person’s body.

Like hemoglobin levels, measurements of other blood traits can be informative about health. An abnormally high white blood cell count and platelet volume have both been linked to an increased risk for heart attack. These measurements can also indicate the presence of infectious disease, immunological disorders or cancers.

Nicole Soranzo and her colleagues in the HaemGen consortium measured hemoglobin concentration (Hb), red blood cell count (RBC), red blood cell volume (MCV), platelet count (PLT), platelet volume (MPV), white blood cell count (WBC), the amount of hemoglobin per red blood cell (mean corpuscular hemoglobin content, or MCH), and the amount of hemoglobin relative to the size of the cell (mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, or MCHC) in more than 14,000 healthy individuals from Europe. They found sixteen new genetic associations with blood traits from fifteen genomic regions not previously thought to be involved.

Santhi Ganesh and her colleagues in the CHARGE consortium measured Hb, MCV, RBC, MCH, MCHC, and the percent of red blood cells in whole blood (hematocrit, or Hct) in more than 24,000 Caucasian individuals from the U.S. and Europe. Here, they found nine new associated variants from eleven previously unassociated genomic regions.

One of the advantages of these studies is the number of traits that they analyzed.

“Until now, few genome-wide association studies have looked beyond single traits,” said co-author Christian Geiger. “But, through a systematic analysis of correlated traits we can begin to discover such shared genetic variants, forming the basis for understanding how these processes interact to influence health and disease.”

Coronary Artery Disease

Both teams noted several genomic regions that play a broad role in blood-related health. The HBS1L-MYB, TFR2-EPO, TMPRSS6 and HFE regions were all associated with at least three different traits. These regions have also been connected to fetal hemoglobin levels. They’re also connected to the iron-overload condition hemochromatosis. Of these newly associated variants, many are close to genes that present promising candidates for further research.

Soranzo’s team went further by investigating whether two of the variants associated with increased platelet volume (PLT) were also associated with coronary artery disease. They analyzed these SNPs in about 9,500 people with coronary artery disease and 10,500 healthy controls. They found that both variants increased odds of coronary artery disease by about 1.15 times.

Protection from Infection

When the researchers looked more closely at the region where and are located, they found a block of ten SNPs that tend to be inherited together. They are all associated with increased PLT and risk of coronary artery disease. They also confirmed previous findings from other researchers of association between celiac disease and type 1 diabetes with SNPs in this block.

Data for chimpanzees and multiple human populations point to a relatively recent event in human evolution. This was where the above-mentioned genetic variants swept across European populations. However this was not the case in East Asian or African populations.

The block of SNPs is located in an area of the genome involved in immune response. The authors suggest that these mutations may have given some populations a survival advantage against infection, despite increasing the risk for certain diseases.