Many people who carry a BRCA genetic variant associated with an increased risk for breast, ovarian, prostate, and certain other cancers do not have a strong family history of cancer, according to a new study from 23andMe. This means that these individuals would likely not qualify for clinical genetic testing unless they developed cancer themselves, representing a missed opportunity for cancer prevention.

The study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, could help inform the on-going discussion around broader access to BRCA genetic testing.

“Our study suggests that many individuals with a BRCA variant are likely being missed under current testing criteria,” said Ruth Tennen Ph.D., a 23andMe Product Scientist and a co-author of the study.

Cancer History and Ashkenazi Ancestry

The study is consistent with findings from other researchers suggesting many individuals who carry BRCA risk variants slip through the cracks in current testing. A recent study by researchers at Geisinger reported that more than 80 percent of people with a BRCA variant did not know they have one.

Current clinical criteria for BRCA genetic testing include having a personal or family history of cancer. Having Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry is also taken into consideration.

But the 23andMe study found that a significant number of individuals with one of three BRCA risk variants common among Ashkenazi Jews have no known first-degree family history of a BRCA-related cancer or no known Jewish ancestry.

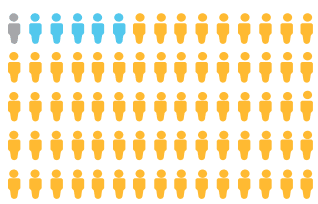

About 44 percent of individuals who provided both ancestry and family health history information had no first-degree relative with a BRCA-related cancer, the study found. The researchers also found that 21 percent of individuals who had one of the three Ashkenazi Jewish BRCA1 or BRCA2 founder variants did not report having Jewish ancestry. But of those individuals, more than half did have detectable Ashkenazi Jewish genetic ancestry. In the absence of a personal history of cancer, these individuals would have been unlikely to qualify for clinical genetic testing, and would have been left unaware of their risk.

23andMe Study Details

The study included data from more than 2,800 23andMe customers who consented to participate in research. All of those individuals carry one or more of the three genetic variants in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes included in 23andMe’s BRCA1/BRCA2 (Selected Variants) Genetic Health Risk report* that are associated with an increased risk for breast, ovarian, prostate, and certain other cancers.

While these three variants are most commonly found in people of Ashkenazi ancestry, they confer significant risk no matter a person’s ancestry. The prevalence of these three variants is about 1 in 40 in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. In the general population, about 1 in 300 to 1 in 800 individuals has a BRCA variant, although typically not one of the three variants included in 23andMe’s report. Women with a BRCA variant have a 45-85 percent chance of developing breast cancer and up to a 46 percent chance of developing ovarian cancer by age 70. Men with a BRCA variant have an increased risk for male breast cancer and may have an increased risk for prostate cancer. Having one of these variants may also increase the risk for pancreatic cancer and melanoma.

23andMe’s Genetic Health Risk Report

You can learn more about BRCA here.

It’s important to understand that 23andMe’s BRCA1/BRCA2 (Selected Variants) Genetic Health Risk report* looks at just three genetic variants associated with increased risk for breast, ovarian, prostate, and certain other cancers. 23andMe is still the only company with FDA authorization to offer direct-to-consumer genetic health risk reports for cancer predisposition. The report is by no means a comprehensive screen, nor is it meant to be diagnostic. There are more than 1,000 other BRCA variants associated with increased cancer risk.

This study focused on just the three variants 23andMe tests for because they have been analytically validated on the most recent versions of 23andMe’s genotyping chip. For these three risk variants, 23andMe has demonstrated a greater than 99 percent accuracy and reproducibility in testing.

Several years ago, 23andMe conducted a smaller study looking at the response to unexpected BRCA findings. That study found that those who learned they carried a risk variant generally took appropriate actions, talking to their doctors and sharing their results with family members, creating what the study called a “cascade effect” that benefited relatives who might not know of the family risk for these hereditary cancers.

The 23andMe study published this week may help inform discussions about broader access to BRCA genetic testing.

*The 23andMe PGS test uses qualitative genotyping to detect select clinically relevant variants in the genomic DNA of adults from saliva for the purpose of reporting and interpreting genetic health risks, including the 23andMe PGS Genetic Health Risk Report for BRCA1/BRCA2 (Selected Variants). Your ethnicity may affect the relevance of each report and how your genetic health risk results are interpreted. The test is not intended to diagnose any disease and does not describe a person’s overall risk of developing any type of cancer. It is not intended to tell you anything about your current state of health, or to be used to make medical decisions, including whether or not you should take a medication, how much of a medication you should take, or determine any treatments. Warnings & Limitations: The 23andMe PGS Genetic Health RIsk Report for BRCA1/BRCA2 (Selected Variants) is indicated for reporting of the 185delAG and 5382insC variants in the BRCA1 gene and the 6174delT variant in the BRCA2 gene. The report describes if a woman is at increased risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, and if a man is at increased risk of developing breast cancer or may be at increased risk of developing prostate cancer. The three variants included in this report are most common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and do not represent the majority of BRCA1/BRCA2 variants in the general population. This report does not include variants in other genes linked to hereditary cancers and the absence of variants included in this report does not rule out the presence of other genetic variants that may impact cancer risk. The PGS test is not a substitute for visits to a healthcare professional for recommended screenings or appropriate follow-up. Results should be confirmed in a clinical setting before taking any medical action.