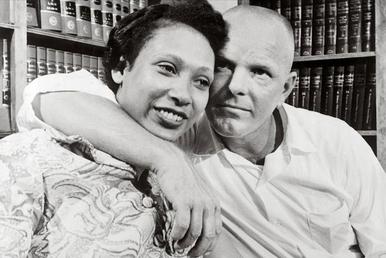

A generation ago it was a felony to marry across racial lines in Virginia and 15 other states in the south, and the repercussions of those laws are still felt today.

Mildred Jeter and Ricahrd Loving, the couple who were at the center of the US Supreme Court Case Loving v. Virginia that struck down laws against interracial marriage.

The movie “Loving” tells one side of that story, the moving tale of Mildred and Richard Loving, who defied the law and married. The couple’s almost decade-long legal fight ended in 1967 with the landmark Supreme Court ruling, Loving v. Virginia, which erased laws in 16 states that prohibited marrying outside your race.

This week marks the anniversary of that case.

For many other couples that crossed racial lines and dared to fall in love in those years, the Loving case came too late. Their stories have yet to be told.

Katrina Callsen, a young mom and law student in Virginia, only recently uncovered her own family’s side of that story using 23andMe.

Her dad, Clarence, a retired Army sergeant first class, was adopted at birth and never knew anything about his biological parents, but with the help of his daughter’s 23andMe results he was able to learn his story for the first time.

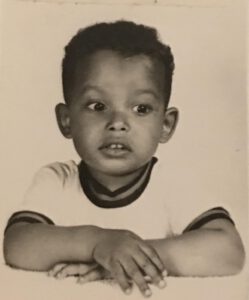

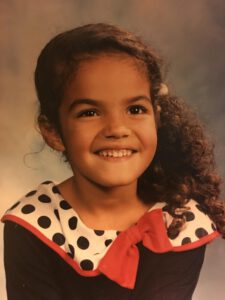

Clarence as a child.

Clarence’s father was black, and his mother was white. They were young and in love, but they lived at a time and in a place, Virginia, where mixed race couples could not legally get married.

When Clarence’s birth mom became pregnant she and his birth father said they couldn’t get married and she didn’t feel she could keep a black child, Katrina said.

After giving up Clarence, the couple never saw their son, or each other again.

Fifty years later, as Clarence pieced together the story. With the help of 23andMe and Clarence’s daughter, Katrina, he was first able to find his biological father by first connecting with a cousin, who also happened to live in the same town and only a few blocks away.

“My dad is an adoptee from a completely closed adoption and I did 23andme to gain some ancestry and health related insights,” Katrina said.

By testing she learned that her dad was also mixed race, she said.

“When I got my 23andme results back and found out I had a cousin living down the street from me,” she said

It was through this cousin that Clarence and Katrina were able to find out who his father was.

Now 85, Clarence’s biological father had never told anyone — his wife or stepchildren — that he had had a child.

Katrina as a child.

When Clarence was finally able to meet him in person, he told his son that his biological mother was white, and although they had wanted to, at the time it was illegal for them to marry in Virginia.

“My biological grandpa told my father he thought of him many times and … made a plea to meet him before it was too late, and there he was delivered on his doorstep,” Katrina said.

After that initial meeting and using information that Clarence’s father shared, he and Katrina were later able to find his birth mother.

She too had kept his birth secret, and the agony she had at having to give up her son.

Some of the emotion around that history is still raw, and both of Clarence’s birth parents coming to terms with finding their son. For their part, Clarence and Katrina have asked that his birth parents names not be used to respect their privacy, and allow Clarence time to get to know them and their families.

For Katrina the story brings full circle a painful personal and national history. Recently, Katrina and her dad spoke on a panel moderated by lifestyle blogger Serein Wu, at the Mixed Remixed festival in Los Angeles celebrating the anniversary of the Loving case, and shared their story.

“Got us all in tears in here,” Tweeted Katy Monty after listening to Katrina and her dad talk about finding his biological family.

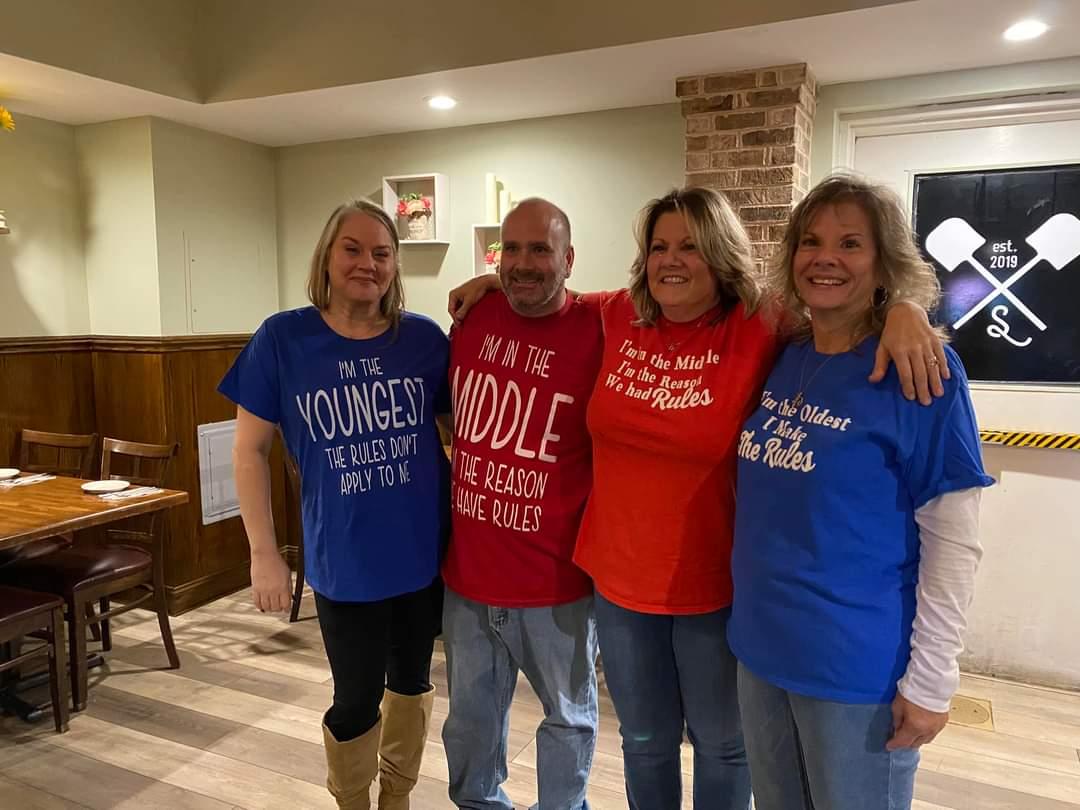

Even after the law changed, biracial couples have struggled. Katrina said her parents also faced some of those same tensions. Clarence is black and Katrina’s mom is white, and initially their parents did not embrace the marriage. But their mixed race children grew up in a different time.

“Thirty years and four kids later they are still together,” said Katrina.

Clarence and Katrina at the Mixed Remixed festival in Los Angeles with moderator Serein Wu.

And making this connection and learning of the story of her dad’s birth has been important for Katrina and her father. Finding family roots, history and relatives has connected them to their history. Even Katrina’s move to Charlottesville to attend law school feels to be part of that. Her biological family has deep roots there and she herself feels connected to the place, a connection that — as the daughter of an Army NCO who regularly moved every few years — she’d never had before.

“It is hard, if not impossible, to put in words what it means to suddenly find a biological family, to find roots, to realize that the place you have felt naturally drawn to holds centuries of your family history,” Katrina said. “Genetics can hold stories and answers we didn’t even know we were seeking. It can show you the family you never knew, who lives around the corner, and is overjoyed to welcome you back home.”