Editor’s note: For Juneteenth we’re republishing a post from earlier this year about connecting a woman and her family to the remains of a little girl buried among those of other enslaved African Americans near a historic iron furnace in Maryland.

Agnes Jackson lives in Hagerstown, Maryland, near her four daughters and about 20 miles from the Catoctin Furnace, a historic site.

This long-ago shuttered iron smelter is one of the earliest industrial sites in the United States. The old iron furnace is on the edge of the Catoctin Mountain National Park, a verdant open space blanketed in forest and lined with hiking trails along the edge of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

An Iron Furnace

The beauty of the place belies the brutal conditions that once made up the day-to-day lives of the free and enslaved African Americans who lived and worked there.

Until recently, Agnes, who is 86, knew little of that history or her deep connection to those who lived and worked there.

Despite living so close, Agnes and her daughters visited Catoctin for the first time only about a year ago, soon after she learned about her family’s link to the site.

“We never knew,” Agnes said during a visit to the site last year.

With the help of the local archaeologist and president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, Elizabeth Comer, and groundbreaking research from scientists at Harvard, the Smithsonian, and 23andMe, Agnes and her family are seeing for the first time all the threads that connect them to this place and the people who toiled here.

Elizabeth, who perhaps has spent more time than anyone trying to document the legacy of the people who worked at the furnace, said adding the DNA component to this research connects this early American history to the living.

“What DNA does for the first time is connect a living, 21st-century family not just to Catoctin but to the cemetery,” she recently told Science magazine.

Groundbreaking Genetic Study

Earlier this month, Elizabeth and 23andMe scientist Éadaoin Harney visited with Agnes and three of her daughters, Sharon Green, Vicki Winston, and Barbara Hart, at a museum commemorating the Catoctin Furnace and the enslaved and free people who worked there.

Éadaoin was the lead author of a study published in the journal Science last year. The other researchers in the study included senior authors David Reich at Harvard and Doug Owsley at the Smithsonian. The researchers sequenced and studied genetic data from the remains of 27 anonymous enslaved and freed African Americans buried at the site.

The remains were uncovered decades ago during a highway construction project and buried in an unmarked burial ground. Researchers noted that the genetically related individuals were clustered into five family groups: mothers, children, and siblings.

The study leveraged 23andMe’s extensive research database to find genetic connections between those anonymous individuals and more than 41,000 relatives, although most of whom are very distantly related. The paper broke new ground by providing a technical and ethical benchmark for future studies of similar, largely forgotten burial sites. Agnes and her family were the first of the living close relatives to be informed that they share a previously unknown genetic connection to a historical individual using the first-of-its-kind approach developed by 23andMe researchers for this study.

When the paper was published in August 2023, Carter Clinton, an African American geneticist at North Carolina State University, said the research was “significant for every African American in the country.”

The Human Connection

For Agnes, it was also personal. One of those family groups that the study identified at the Catoctin site included the remains of a young girl between the ages of two and three years old. There were few artifacts with the body, just some pins, nails, and screws found with her remains. The nails and screws were likely the only surviving remnants of the coffin she was buried in, and one of the pins was perhaps used to hold back the little girl’s hair, some of the researchers suspect. The other pins were likely used to fasten a burial shroud.

Comparing the genetic sequence of this little girl with Agnes, Éadaoin and the team of scientists saw a large amount of shared DNA, indicating they were relatively closely related. The most likely connection is with Agnes’s great-great-grandfather, Hanson Summers. It’s possible that Hanson and the girl were half-siblings or cousins.

Often, there is family lore, stories passed down from generation to generation, but it is rare for African Americans to trace back their family history, often hitting the brick wall of slavery. Often, historical records for those enslaved ancestors are spotty. Names may never have been recorded or are only partially recorded.

For Agnes’s family, it was no different. She knew nothing of her family’s connection to the iron furnace. That changed a few years ago during this study when researchers from the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society, who had been attempting for years to find living descendants, had their first success. Elizabeth helped connect Agnes’s family to the furnace using paper records and historical sleuthing. The connection was through her great-great-grandfather, Hanson “Henson” Summers, who’d been enslaved at the iron furnace site in the early 19th century.

A Family’s History and American History

The family, of course, knew that their ancestors had been enslaved. They knew he’d worked at the Antietam Furnace that operated in Hagerstown, but they didn’t know they were linked to the Catoctin Furnace until Elizabeth connected them.

Hanson had been enslaved at Catoctin until he was in his 30s, at which point he and other members of his family were sold to the operators of the Antietam Furnace, according to the records.

After the end of slavery, Hanson worked at an iron forge. Known for his strength and skill, he died in Hagerstown at 82 in 1899. Elizabeth’s work first found mention of Hanson in Maryland archives from 1834. His name was included on an inventory from Catoctin Furnace that included the names of enslaved African Americans. On it was a 17-year-old boy named “Henson.”

The Catoctin Furnace has a significant place in American history.

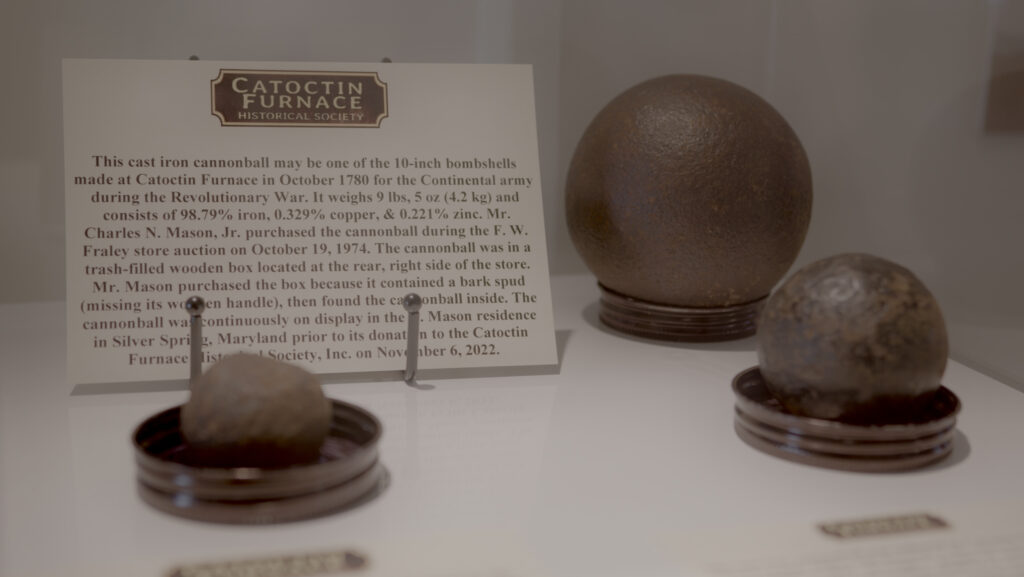

The first owner of the furnace was Thomas Johnson Jr. — a wealthy enslaver, the first non-colonial governor of Maryland, and a signer of the Articles of Association, a precursor document to the Declaration of Independence. Iron production began in earnest in 1776. It contributed to the arming of the fledgling Continental Army — supplying 100 tons of shells for the Siege of Yorktown. While historians documented the industrial significance of the site, the history of enslaved workers there was not.

We Built This

Agnes and her family didn’t know their family’s contribution to that history. Agnes said that learning about her ancestors’ contributions was important.

“Just to know that we actually were in history and that we made a difference,” she said. “We built this place.”

That history might have remained lost had it not been a forgotten burial ground, which had been unearthed in the 1970s during a freeway construction project. Archaeologists found the remains of more than 30 individuals buried there. No records existed of who those individuals were. Over the years, the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society has worked to preserve the history of the site and the people who worked there. Only with the advent of ancient DNA technology did an effort to learn more about the DNA of individuals begin.

This study offered the first genetic link between enslaved or freed African Americans working at the furnace and their living relatives, including Agnes.

“It’s so exciting to see my tree… to learn more about our ancestors,” Agnes said. It’s always good to know where we came from.”