Even after a best-selling book and countless articles, few of us know the name Henrietta Lacks — but we should.

Henrietta Lacks

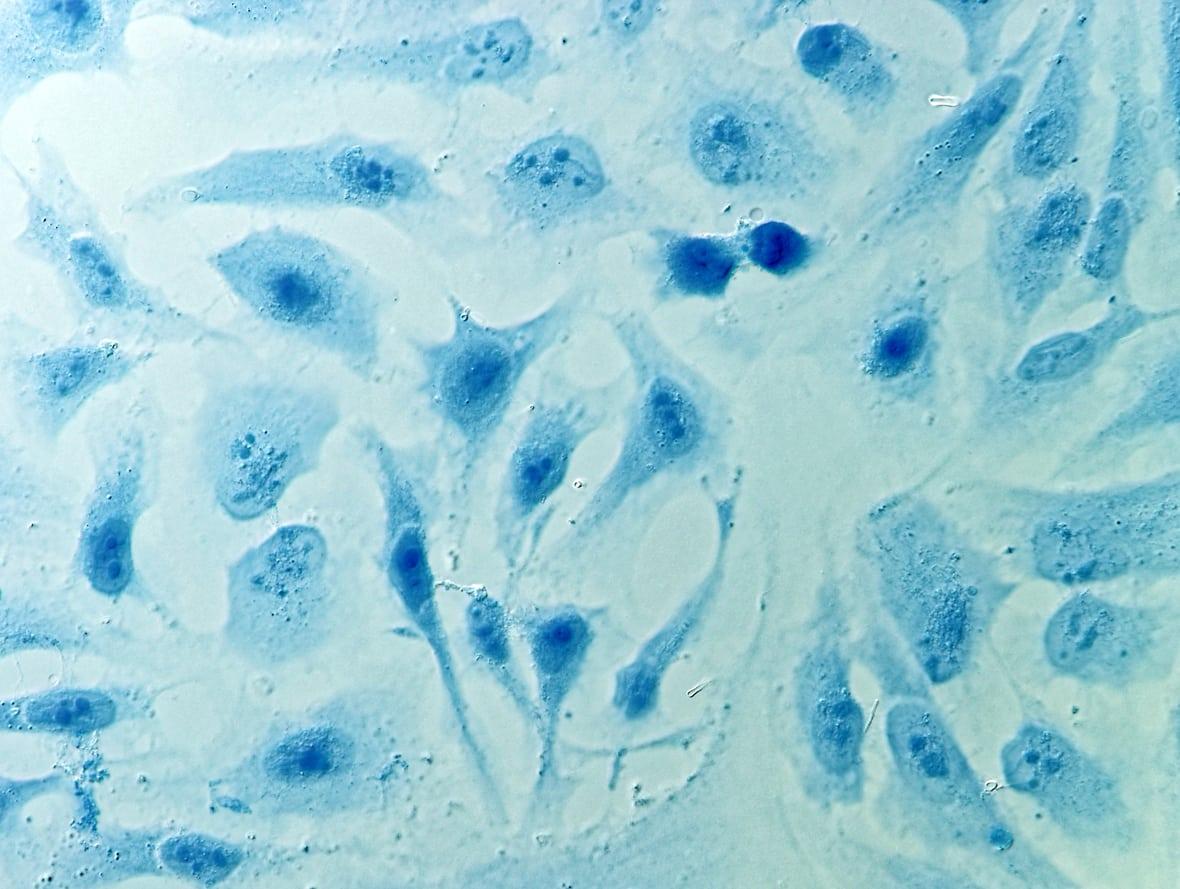

The young African American mother of five, who died in 1951 of an aggressive form of cervical cancer, has remained a hidden figure in our history. Yet her contributions to science — in the form of the human cancer cells cultured from her body — have transformed medicine. These immortal “HeLa cells”, as scientists dubbed them, have been vital for the development of everything from the polio vaccine, to chemotherapy drugs, HPV treatments, in-vitro fertilization and gene mapping. And the cells are still being used today, critical in important research. It’s distressing to learn now that at the time it never occured to doctors or scientists to even ask Henrietta or her family for permission.

This week 23andMe participated in an event to honor Henrietta Lacks’ contribution to science. Put together by African American Community Health Advisory Committee, in partnership with the San Francisco-Peninsula Alumnae Chapter, Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc., and the County of San Mateo, California, the event included two members of the Henrietta’s family in part to help bring awareness of health issues for people of color.

The tragedy of Henrietta’s death, and the loss experienced by her husband and children, was compounded by the fact that no one ever told her family that her cells had been taken and cultured for research. Major breakthroughs were made, and so were billions of dollars, but her family — who lived in the shadow of the world-renowned John’s Hopkins Hospital where some of this research took place — was kept in the dark for decades. They first learned about what was happening when scientists reached out to them for additional blood samples. And in an irony of this story, while Henrietta’s cells were so vital for medical research, many of her family members lived without basic health insurance. At the event this week, her grandson Frank Lacks was there to encourage people to learn from her story. The lesson isn’t that underrepresented people should walk away from participating in this kind of research, said Frank, they should be demanding a seat at the table so they too can benefit from it.

Henrietta’s story, so ably told in Rebecca Skloot’s 2010 book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and in a new HBO Films movie starring Oprah Winfrey, is both moving and important for finally recognizing the contribution of this hidden hero.

Her story also reminds us of how far we’ve come, and how important one person, like Henrietta, could be for research. It also highlights how much more needs to be done to improve health research in underrepresented populations.

After years of developing 23andMe’s unique research model — one that enlists people as participants in research, not subjects to it — we’ve learned that people want to participate in important science, and more than 80 percent of our customers choose to participate in research. But our research participants also want to know and have control over how their information is being used. They want the choice to participate, or not, an option Henrietta never had. They do not want someone else making that choice for them. They want to know what happens to their data, and when a discovery is made, they want to hear about it. 23andMe works toward being as transparent with our own customers as possible, sharing with them information about research we do using customer data, and giving customers control over whether or not they want to share their data. 23andMe also gives participants the option of opting out of research at any time. For more please read our privacy statement, terms of service, our consent form, or visit our bibliography cataloguing our research.

Henrietta didn’t just help power scientific research: Her story helped transform how researchers treat people who participate in scientific studies. Research on human subjects now must be overseen by independent review boards to ensure that participants understand the research being done with their information, that they are not harmed by that research, and that their interests are protected.

For all of that and more we owe our thanks to Henrietta, and we should each learn more about her story. It was also a fitting way to begin Black History Month.

To Learn More

- Henrietta Lacks Foundation

- Rebecca Skloot, author of the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

- HBO Films “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”

- HeLa Cells: A New Chapter in an Enduring Story, blog by NIH Director Francis Collins

- NIH Henrietta Lacks Timeline